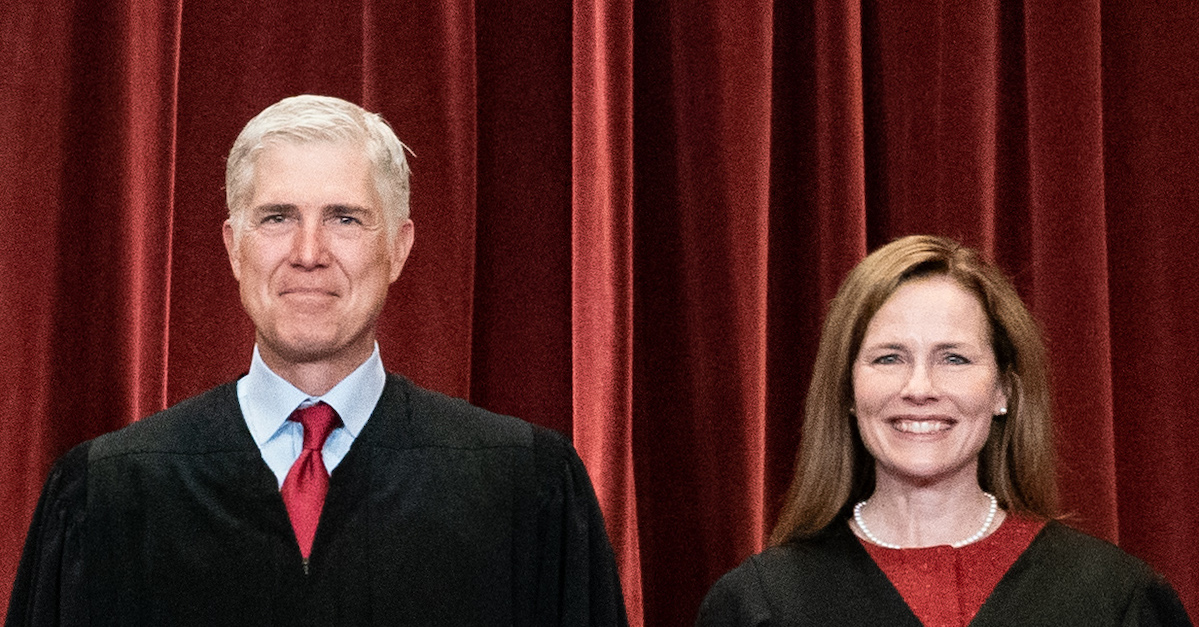

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 23: Members of the Supreme Court pose for a group photo at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021. Seated from left: Associate Justice Samuel Alito, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John Roberts, Associate Justice Stephen Breyer and Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Standing from left: Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Associate Justice Elena Kagan, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch and Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett. (Photo by Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images)

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday ruled against immigrants seeking judicial review of mistakes and errors made by immigration agencies. In a 5-4 majority opinion, Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote that federal courts are categorically barred from considering such issues.

“It is no secret that when processing applications, licenses, and permits the government sometimes makes mistakes,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in a passionate dissent. “Often, they are small ones—a misspelled name, a misplaced application. But sometimes a bureaucratic mistake can have life-changing consequences. Our case is such a case.”

Joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, Gorsuch castigated the sweeping nature of the majority’s decision and its fealty to the administrative state.

“Today, the Court holds that a federal bureaucracy can make an obvious factual error, one that will result in an individual’s removal from this country, and nothing can be done about it,” the dissent notes. “No court may even hear the case. It is a bold claim promising dire consequences for countless lawful immigrants.”

In the case stylized as Patel v. Garland, Pankajkumar Patel, who has lived in the country for nearly 30 years, accidentally ticked the wrong box on a driver’s license application question about his citizenship status in Georgia. Peach State prosecutors initially pressed charges but later determined that they lacked evidence to prove a crime had been committed. Notably, his incorrect check mark didn’t have any bearing on his request for a driver’s license because under Georgia law, he was entitled to one even though he wasn’t a U.S. citizen because he had filed for a green card and had a valid work permit.

The Department of Homeland Security rejected Patel’s green card application on the basis of a statute barring immigration status adjustments to anyone who “falsely represents . . . himself . . . to be a citizen of the United States” to obtain a “benefit under . . . State law.”

After that, the government initiated deportation proceedings against Patel, who has three children who also live in the country. He then re-filed his green card application under the relevant statutes and repeated his consistent claims about his lack of intent to deceive and how Georgia law regarding that benefit–the driver’s license–wasn’t actually contingent on how he filled out the form in the first place.

“None of this moved the immigration judge,” Gorsuch writes. “He said he did not believe Mr. Patel’s testimony that he checked the wrong box mistakenly. Instead, the immigration judge found, Mr. Patel intentionally represented himself falsely to obtain a benefit under state law. According to the immigration judge, Mr. Patel had a strong incentive to deceive state officials because he could not have obtained a Georgia driver’s license if he had disclosed he was ‘neither a citizen [n]or a lawful permanent resident.'”

But the immigration judge was incorrect. Patel followed up and said exactly as much before the Board of Immigration Appeals.

SEE ALSO: SCOTUS Considers Role of Judges in Green Card Proceedings

“In his appeal, Mr. Patel argued that the immigration judge’s finding that he had an incentive to deceive state officials was simply wrong—under Georgia law he was entitled to a driver’s license without being a citizen or a lawful permanent resident given his pending application for adjustment of status and permission to work,” the dissent notes. “Mr. Patel submitted, too, that all the record evidence pointed to the conclusion he simply checked the wrong box by mistake; even state officials agreed they had no case to bring against him for deception.”

The agency tribunal ruled against him. In additional appeals, with the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, various federal judges opined at length about whether or not they even had the ability to review Patel’s case. In their first ruling against him, a three-judge panel determined they lacked jurisdiction to even hear the case.

Patel appealed again. The full court then decided, in a 9-5 opinion, that one small bit of statutory language precludes courts from reviewing cases like Patel’s–while also noting that they had to overrule “numerous” precedents in various circuits in order to reach the conclusion that they can’t really consider such cases at all.

The statute reads, in relevant part:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law . . . and regardless of whether the judgment, decision, or action is made in removal proceedings, no court shall have jurisdiction to review— (i) any judgment regarding the granting of relief under section . . . 1255 of this title.

Under federal law, there’s a two-step process for whether or not an immigrant is entitled to relief from a deportation decision. The first step is whether or not an immigrant is entitled to having their status adjusted. The next step is whether or not, in the government’s discretion, they might then not be deported.

In Patel’s case, the judge, the BIA, and the 11th Circuit ruled against him at step one. The 11th Circuit’s logic was that the above-referenced statute foreclosed against a court hearing anything about how the agency had erred at the first step. The second step was never even considered by the court. Barrett’s majority opinion endorses that view.

Gorsuch explains (and criticizes) at length:

Following the Eleventh Circuit’s lead, the majority contends that subparagraph (B)(i)’s phrase “any judgment regarding the granting of relief under § 1255” sweeps more broadly. On its account, the statute denies courts the power to correct all agency decisions with respect to an adjustment-of-status application under § 1255—both the agency’s step-one eligibility decisions and its step-two discretionary decisions. As a result, no court may correct even the agency’s most egregious factual mistakes about an individual’s statutory eligibility for relief. It is a novel reading of a 25-year-old statute. One at odds with background law permitting judicial review.

“It does not matter if the BIA and immigration judge in Mr. Patel’s case erred badly when they found he harbored an intent to deceive state officials,” the dissent goes on. “It does not matter if the BIA declares other individuals ineligible for relief based on even more obvious factual errors. On the majority’s telling, courts are powerless to correct bureaucratic mistakes like these no matter how grave they may be.”

The dissent even repeats some of its own language verbatim but with added italics to stress the points:

[U]nder the majority’s construction of subparagraph (B)(i), individuals who could once secure judicial review to correct administrative errors at step one in district court are now, after its decision, likely left with no avenue for judicial relief of any kind. An agency may err about the facts, the law, or even the Constitution and nothing can be done about it.

Gorsuch goes on to note that tens of thousands of such rejections are handed out by agency officials each year and argues that Barrett’s opinion “will almost surely end all that and foreclose judicial review for countless law-abiding individuals whose lives may be upended by bureaucratic misfeasance.”

Read the opinion and dissent, below:

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]