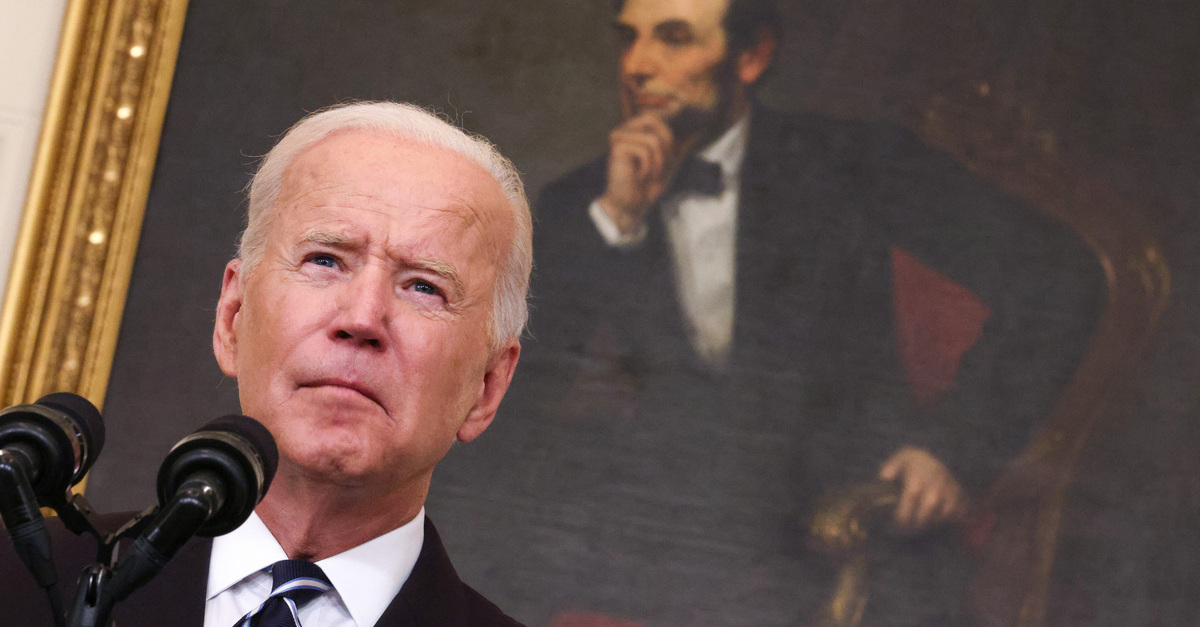

On the eve of a public hearing, President Joe Biden’s commission released a series of reports on various proposals to reform the Supreme Court. The report appeared to reject the idea of expanding the court, receptive to term limits for justices, and proposed confronting the so-called “shadow docket” with increased transparency.

Setting out explicitly to avoid “partisan conflict” and “polarization,” the commission disappointed many on the Democratic Party’s left flank by criticizing the idea of adding justices to the Supreme Court — a theory described as “expansion” by its supporters and “court packing” by its critics. Former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt proposed the idea nearly a century ago to keep the court from shooting down the most ambitious aspects of his New Deal agenda, but Congress never enacted it, and Associate Justice Owen Roberts famously shifted his jurisprudential views regarding the constitutionality of the administrative state to more closely align with those of the FDR administration.

In five sets of reports — stylized as “Discussion Materials” — the commission lays out the history of the debate before chiming in on various proposals.

“Reinforce the Notion That Justices Are Partisan Actors”

From its 46-page treatise “Membership and Size of the Court,” the commission was no more bullish on the idea, questioning the benefit leveling out the partisan affiliations of the justices.

It is “far from clear that ideological balance is in and of itself a desirable goal,” they wrote.

“If there is no such balance in the political branches, requiring such balance on the Court could make it insufficiently responsive to electoral outcomes,” the materials state. “In other words, if the goal were to ensure that the Court roughly reflects the public will and exhibits a degree of responsiveness to the political composition of the people at a given time, artificial balance between the two political parties would not achieve that objective. A balanced bench could be preferable to the status quo for those observers of the Court who perceive a significant mismatch between its composition today and the body politics. [sic] But institutionalizing such a requirement could block or would not be preferable to farther reaching change.”

Justices appointed by both parties—including Stephen Breyer, Amy Coney Barrett, and Samuel Alito—have lashed out at public commentators depicting them as political actors, even when indignantly declaring their neutrality in explicitly partisan settings.

“My goal today is to convince you that this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks,” Barrett said in September, after being introduced by the Senate’s top Republican Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). Breyer, one of the liberal justices, appeared on Fox News to echo similar sentiments, and Alito criticized a piece written by The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer, who in turn slammed the justice’s “delusions of impartiality.”

Biden’s Commission appeared to tilt toward the justices’ points of view.

“What is more, an explicit requirement that Justices be affiliated with particular parties would constrain the pool of potential nominees and reinforce the notion that Justices are partisan actors,” they wrote.

“Only Major Constitutional Democracy” without Term Limits

On the other hand, Biden’s Commission—like Justice Breyer—appeared to be receptive to the idea of term limits, even though the Constitution does not dictate the court’s size but does specify lifetime appointments.

“The United States is the only major constitutional democracy in the world that has neither a retirement age nor a fixed term of years for its high court Justices,” the report on term limits states. “Most democracies like ours have term limits for their constitutional courts, and the small number of countries that have ‘life tenure’ provisions for their apex court actually impose age limits.”

The commission noted that the Constitution’s call for lifetime appointments springs from the desire for judicial independence.

“The constitutional principle of judicial independence requires that judges not face any consequences, positive or negative, for how they decide cases,” the report states. “But our system of checks and balances also requires that the elected branches be able to affect the composition of the judiciary through successive appointments.”

Such a proposal would require an amendment to the Constitution, which the commission envisions could contain an 18-year term.

Another section of the report on “Case Selection and Review” speaks extensively about the so-called shadow docket.

“The term ‘shadow docket’ was coined six years ago to describe the Court’s ‘orders and summary decisions that defy its normal procedural regularity,'” the report describes — noting this often occurs via emergency orders.

One idea for reform, the panel notes, calls for greater transparency over important decisions such as over Texas’s anti-abortion law S.B. 8, which was held up by critics as a prime example of a decision decided along partisan lines with little explanation.

The commission noted that confronting the issue, however, could prove tricky.

“To be sure, the category of ‘important’ cases in which explanation may be most valuable is hardly self-defining; reasonable minds will differ over the details,” the report states.

This is a developing story.

(Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)