Many movement conservatives were upset at Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch for ruling in favor of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender rights on Monday in a Civil Rights decision that will almost certainly lead to similarly progressive outcomes in many lower court cases well into the foreseeable future. Civil Rights attorneys and other legal observers were quick to accuse conservatives of letting the mask fall.

One particular sticking point for that widespread criticism from the right purportedly had less to do with the end result than with how, exactly, Gorsuch’s landmark opinion framed its analysis to reach its conclusion.

“When the express terms of a statute give us one answer and extratextual considerations suggest another, it’s no contest,” the decision said. “Only the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.”

Gorsuch’s prose in the above quotation was an all-but explicit appeal to the form of statutory interpretation known as textualism–a formalistic device that has long been embraced by conservative jurists on the Supreme Court (and in other courts) to obtain strict and narrow readings of laws that usually happen to have politically conservative outcomes. The method was avowedly embraced and largely popularized by deceased legendary conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who Gorsuch replaced on the nation’s high court.

Specifically, textualists tend to allege that they are interpreting the statute at hand without any concern whatsoever for non-textual sources. This approach necessarily renders other methods of statutory interpretation–such as legislative intent, legislative history, living constitutionalism and public policy concerns–unsuitable, at least when a judge claims to be using the textualist method.

Gorsuch’s landmark opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia fashions itself in the textualist tradition by using a very basic and simple understanding of what the word “sex” means in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964–an effort that won the approval of fellow conservative Chief Justice John Roberts but which drew outrage from Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh.

“The Court attempts to pass off its decision as the inevitable product of the textualist school of statutory interpretation championed by our late colleague Justice [Antonin] Scalia, but no one should be fooled,” Alito complained in a dissent joined by Thomas. “The Court’s opinion is like a pirate ship. It sails under a textualist flag, but what it actually represents is a theory of statutory interpretation that Justice Scalia excoriated––the theory that courts should ‘update’ old statutes so that they better reflect the current values of society.”

Kavanaugh authored a separate dissent that essentially accused Gorsuch of committing textualist treason.

“Instead of a hard-earned victory won through the democratic process, today’s victory is brought about by judicial dictate – judges latching on to a novel form of living literalism to rewrite ordinary meaning and remake American law,” the second dissent groused.

Off the court, conservatives were also none-too-pleased with Gorsuch’s rhetorical sleight of hand used to protect LGBTQ rights.

“Justice Scalia would be disappointed that his successor has bungled textualism so badly today, for the sake of appealing to college campuses and editorial boards,” tweeted Judicial Crisis Network President Carrie Severino. “This was not judging, this was legislating—a brute force attack on our constitutional system.”

“A ‘textualism’ that finds ‘sex’ to encompass sexual orientation and ‘gender identity’—especially when the latter was not even yet conceived by radical gender theorists at the time of statutory enactment—is not a ‘textualism’ worthy of the name,” tweeted Newsweek opinion editor Josh Hammer.

“Have no doubts about what happened today: This was the hijacking of textualism,” Severino added in the first concluding tweet of many Twitter threads she wrote on Monday’s ruling. “You can’t redefine the meaning of words themselves and still be doing textualism. This is an ominous sign for anyone concerned about the future of representative democracy.”

Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro declared that textualism now means “progressive jurisprudence.”

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) attorney Josh Block pointed out an apparently revealing feature of Severino’s own criticism.

“The argument that textualism is only textualism when it aligns with conservative policy preference is saying the quiet part out loud,” he tweeted.

Democratic Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) said Gorsuch used “pure textualism.”

Other attorneys said that textualism has never actually had any kind of universally accepted definition and is simply a method used to arrive at a desired political outcome.

I’ll give Scalia this much: his jurisprudence was so scattershot & cynically rooted in expediently getting to his personally preferred outcome, that he now has multiple justices screaming at each other in dicta about what “textualism” means (hint: it’s meaningless)

— Joe (@JC_Esq) June 15, 2020

That debate, screaming or otherwise, carried over to many other online forums.

Writing in the right-leaning Volokh Conspiracy law blog, which is now hosted by libertarian publication Reason, George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin actually argued that Gorsuch’s opinion “is well-justified on the basis of textualism—a theory of legal interpretation usually associated with conservatives.”

Reason senior editor Damon Root sees the Bostock ruling as a clear and unalloyed victory for textualism:

It might come as a surprise to find Gorsuch and Scalia playing such big roles in a Supreme Court decision that is being celebrated as a landmark liberal victory. But that misses the point of textualism. In the words of another self-described textualist, the veteran libertarian litigator and current Arizona Supreme Court Justice Clint Bolick, “true textualists will not always agree with the policy results of their decisions.” But “personal policy preferences must yield to the rule of law or we have no rule of law.”

Of course, Scalia himself wasn’t always a textualist. When ruling against gay rights, in particular, he bemoaned the role of the Supreme Court entirely–preferring to yield to majoritarian impulses in order to keep “a committee of nine unelected lawyers” away from interpreting the Constitution specifically from protecting such rights.

Bryan A. Garner, the so-called “Scalia Whisperer,” argued that Scalia would have sided with Alito if he were alive today.

“Scalia J. would have been with Alito J. in dissent because the nobody-ever-thought-it-meant-that line of reasoning carried a lot of weight with him. (For what it matters [not a whit!], I’d have been with Gorsuch J.),” Garner commented. “The important thing is that all the opinions were TEXTUALIST.”

Scalia and Garner, the editor in chief of Black’s Law Dictionary, co-authored the book, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts.

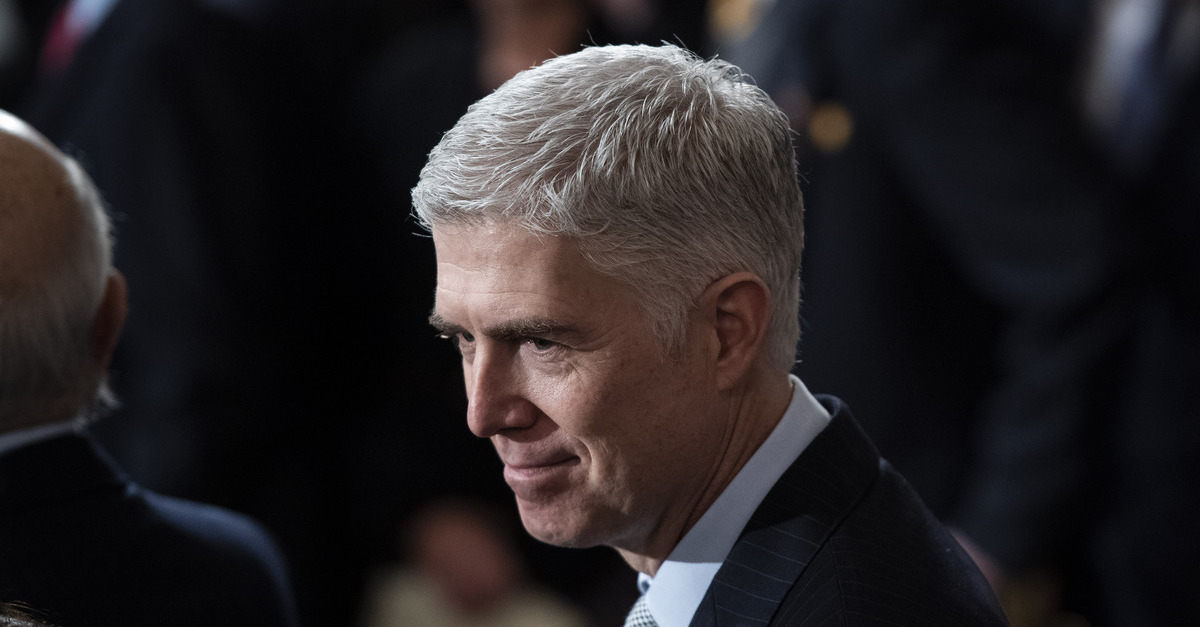

[image via Jabin Botsford – Pool/Getty Images]