The U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday, in a 7-2 opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, diminished the government’s ability to obtain certain sentencing enhancements for attempted federal robbery.

In the case stylized as U.S. v. Taylor, Justin Taylor challenged his conviction under a federal statute that tacked on an additional 10-year sentence for using a firearm in a so-called “crime of violence.”

During the underlying crime, Taylor and an accomplice pulled a gun on a drug dealer in a botched robbery attempt. Taylor’s accomplice shot and killed the man. Ultimately, Taylor took a plea deal – admitting legal culpability for a violation of the federal anti-robbery statute known as the Hobbs Act. Taylor also originally accepted the sentencing enhancement contained under a separate section of federal law.

In 2019, the nation’s high court severely limited the way in which the two statutes can operate together by finding that a “crime of violence” as defined in the sentencing enhancement statute’s residual clause was “unconstitutionally vague” and therefore inoperative. After that change in law, Taylor filed a habeas petition, seeking to retroactively have the extra 10 years of his sentence tossed.

The district court refused. But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled in the inmate’s favor by finding that the sentencing enhancement’s elements clause could not apply to Taylor’s admitted Hobbs act violation. The federal government appealed and the majority of justices sided with the appellate court and Taylor.

In dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas begins by making a point that helps to understand how the majority decided certain gun crimes actually are not violent at all: “Taylor and an accomplice pulled a gun on a fellow drug dealer as they tried to rob him.”

In the end, the facts of Taylor’s case are instructive but not dispositive – or ultimately particularly relevant – to the majority’s analysis. Why? Because Taylor took a plea deal admitting to attempted robbery under the Hobbs Act. And the attempted robbery statute the Hobbs Act doesn’t have any language that makes it a “crime of violence.”

The sentencing enhancement’s elements clause reads:

[T]he term “crime of violence” means an offense that is a felony and

(A) has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another…

Gorsuch explains in legal terms: “no element of the [Hobbs attempted robbery] offense requires the government to prove that the defendant used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force.”

For the majority, the case was an easy call because it’s all there in the two statutes. And they simply don’t gibe together.

“[T]o win a case for attempted Hobbs Act robbery the government must prove two things: (1) The defendant intended to unlawfully take or obtain personal property by means of actual or threatened force, and (2) he completed a ‘substantial step’ toward that end,” the majority notes–emphasis in original. “Whatever one might say about completed Hobbs Act robbery, attempted Hobbs Act robbery does not satisfy the elements clause.”

“Yes, to secure a conviction the government must show an intention to take property by force or threat, along with a substantial step toward achieving that object,” the opinion continues – drawing a clear distinction between intent and use. “But an intention is just that, no more. And whatever a substantial step requires, it does not require the government to prove that the defendant used, attempted to use, or even threatened to use force against another person or his property.”

After running dismissing several of the government’s (and the two separate dissents’) arguments, the majority opinion takes aim at the Biden administration’s last-ditch argument that: (1) case law should overrule the terms of the statute; and that (2) Taylor was unable to cite a single case where the government prosecuted someone without proving that a communicated threat was actually made.

As it turns out, the government was factually wrong on that categorical claim – but it ends up being beside the point. The majority used a typical death-knell description to describe the government’s position: “atextual.”

Gorsuch is witheringly critical here [emphasis in original]:

But what does that prove? Put aside the fact that Mr. Taylor has identified cases in which the government has apparently convicted individuals for attempted Hobbs Act robbery without proving a communicated threat. Put aside the oddity of placing a burden on the defendant to present empirical evidence about the government’s own prosecutorial habits. Put aside, too, the practical challenges such a burden would present in a world where most cases end in plea agreements, and not all of those cases make their way into easily accessible commercial databases…

The government’s theory cannot be squared with the statute’s terms. To determine whether a federal felony qualifies as a crime of violence, § 924(c)(3)(A) doesn’t ask whether the crime is sometimes or even usually associated with communicated threats of force (or, for that matter, with the actual or attempted use of force). It asks whether the government must prove, as an element of its case, the use, attempted use, or threatened use of force.

The key for the majority is what the elements of the underlying crime are. Here, the statute asks, “whether they require the government to prove the use, attempted use, or threatened use of force.” The elements of the crime Taylor pleaded guilty to, attempted robbery, require none of that–but that is what’s required for the sentencing enhancement to apply.

“Accordingly, Mr. Taylor may face up to 20 years in prison for violating the Hobbs Act,” Gorsuch concludes. “But he may not be lawfully convicted and sentenced under § 924(c) to still another decade in federal prison.”

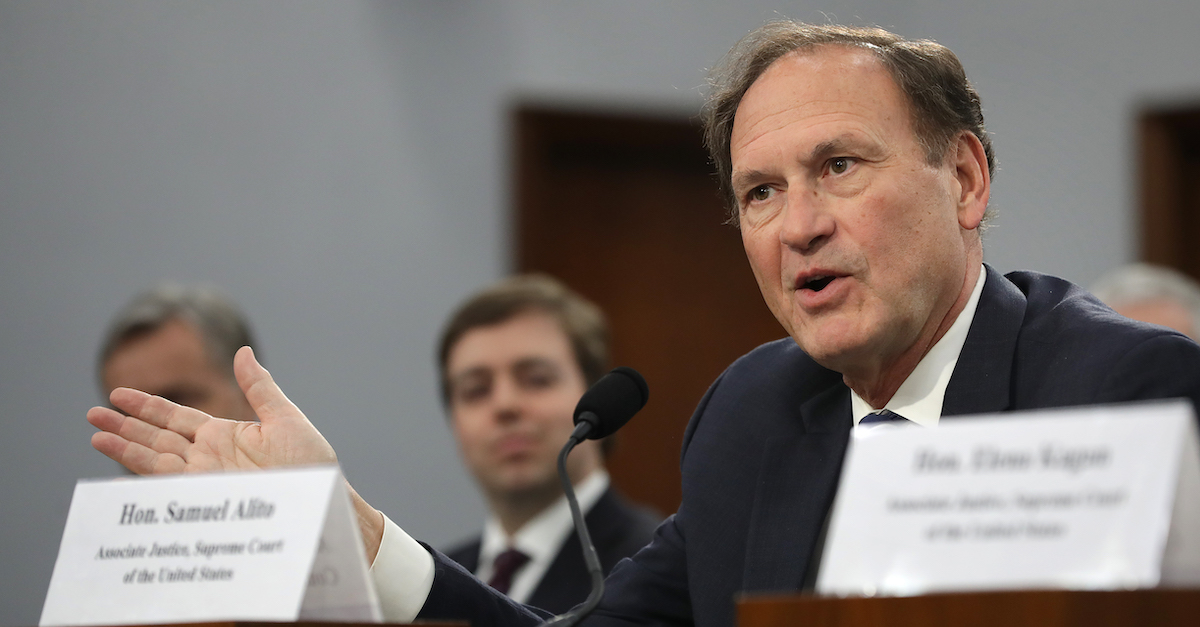

Justice Samuel Alito also filed a dissent, which began with praise for Justice Thomas’s view: “As JUSTICE THOMAS clearly shows, the offense for which respondent Justin Taylor was convicted constituted a ‘violent felony’ in the ordinary sense of the term.”

Alito said he also agreed with Thomas that the Supreme Court’s §924(c)(3)(A) (or “crime of violence”) cases have “veered off into fantasy land.”

[Image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]