The Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear a case challenging the way religious liberty is protected (or, more accurately, isn’t protected) under federal Civil Rights law in orders released Monday morning. Justice Neil Gorsuch strongly took issue with the high court’s decision to once again punt on the question of a decades-old framework used to interpret Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Stylized as Jason Small v. Memphis Light, the case that the textualist justice wanted to hear concerns a Christian man who was approved to take Good Friday off before the company backtracked and docked him two days’ pay when he went to church anyway. This episode was the turning point in a fraught relationship with the company after it previously denied to find him a schedule (and a job with less pay) that would better accommodate his religious beliefs.

On Monday, however, at least five justices declined to entertain Small’s petition for certiorari. Justice Samuel Alito joined Gorsuch’s dissent and it seems both justices would have likely ruled in Small’s favor in order to rectify what they see as a longstanding flaw in Title VII jurisprudence.

Title VII generally prohibits employers from discriminating against individuals on the basis of religion. The statute’s text specifies that this prohibition encompasses “all aspects of religious observance and practice, as well as belief, unless an employer demonstrates that he is unable to reasonably accommodate to an employee’s or prospective employee’s religious observance or practice without undue hardship on the conduct of the employer’s business.”

In 1977, the Supreme Court created the extant framework lower courts use to dispense with Title VII claims in TWA v. Hardison.

“There, this Court dramatically revised—really, undid—Title VII’s undue hardship test,” Gorsuch noted in his dissent to the denial. “Hardison held that an employer does not need to provide a religious accommodation that involves ‘more than a de minimis cost.'”

Gorsuch explained the upshot of Hardison applied to Small’s case:

At no point in the litigation did anyone suggest that Mr. Small’s requested accommodation—reduced pay while he sought reassignment—would have imposed a significant hardship on his employer. Yet both the district court and Sixth Circuit rejected Mr. Small’s claim all the same…

So Mr. Small’s requested accommodation might not have imposed a significant hardship on his employer. The company may extend poorly performing employees the very same relief Mr. Small sought. But the company had no obligation to provide Mr. Small his requested accommodation because doing so would have cost the company something (anything) more than a trivial amount.

“Mr. Small asks us to hear his case and I would grant his petition for review,” the dissent continues. “Hardison’s de minimis cost test does not appear in the statute. The Court announced that standard in a single sentence with little explanation or supporting analysis. Neither party before the Court had even argued for the rule.”

In other words, under the current framework used by the U.S. court system (the Hardison reconfiguration of the “undue hardship” standard), a private employer simply has to show that a religious accommodation will have more than an insignificant impact in order to legally justify denying the requested accommodation.

“Title VII’s right to religious exercise has become the odd man out,” Gorsuch goes on—explaining that other schemes are more protective of other rights. “Alone among comparable statutorily protected civil rights, an employer may dispense with it nearly at whim.”

Gorsuch has leveled his opposition to Hardison before, along with some of the other conservative justices. But Gorsuch has support for remaking Title VII among the ranks of practicing lawyers and from one of the most liberal members to ever sit on the high court’s bench.

At the time Hardison was decided, Justice Thurgood Marshall in dissent said the court’s decision effectively nullifies the religious protections enshrined in Title VII.

“The ultimate tragedy is that despite Congress’ best efforts, one of this Nation’s pillars of strength — our hospitality to religious diversity — has been seriously eroded,” the famed liberal wrote. “All Americans will be a little poorer until today’s decision is erased.”

Appellate attorney Raffi Melkonian noted that the state of affairs with Title VII under Hardison is a perplexing hill to climb for plaintiffs.

“The test is completely without textual basis,” he tweeted, “Just made up. Title VII says only that the employer need not suffer ‘undue hardship.’ SCOTUS inexplicably said that this meant anything more than a de minimis cost. That standard puts an incredible burden on a plaintiff with valid claims. How do you even deal with that? What if it imposes a vague cost to ‘teamwork’ or morale?”

“So I really appreciate Justice Gorsuch’s vendetta here,” Melkonian added.

And Gorsuch made clear that he faulted his peers:

Small insisted that his requested accommodation would not cause an undue hardship under Title VII. Both the district court and court of appeals rejected the argument relying expressly on Hardison. There is no barrier to our review and no one else to blame. The only mistake here is of the Court’s own making—and it is past time for the Court to correct it.

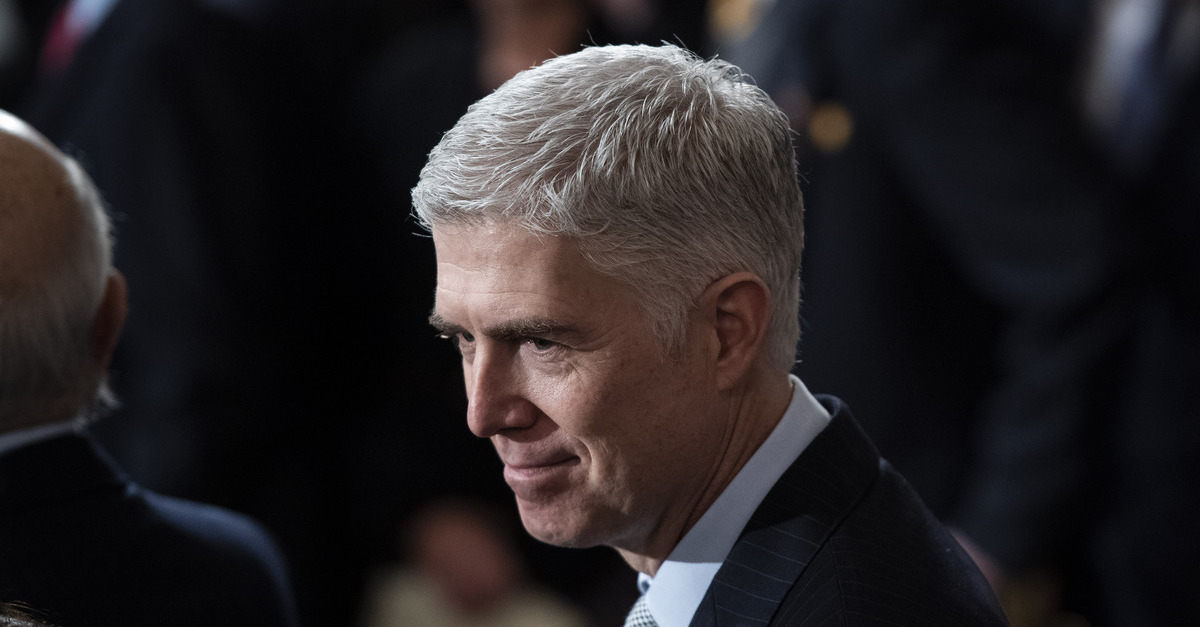

[image via Jabin Botsford – Pool/Getty Images]