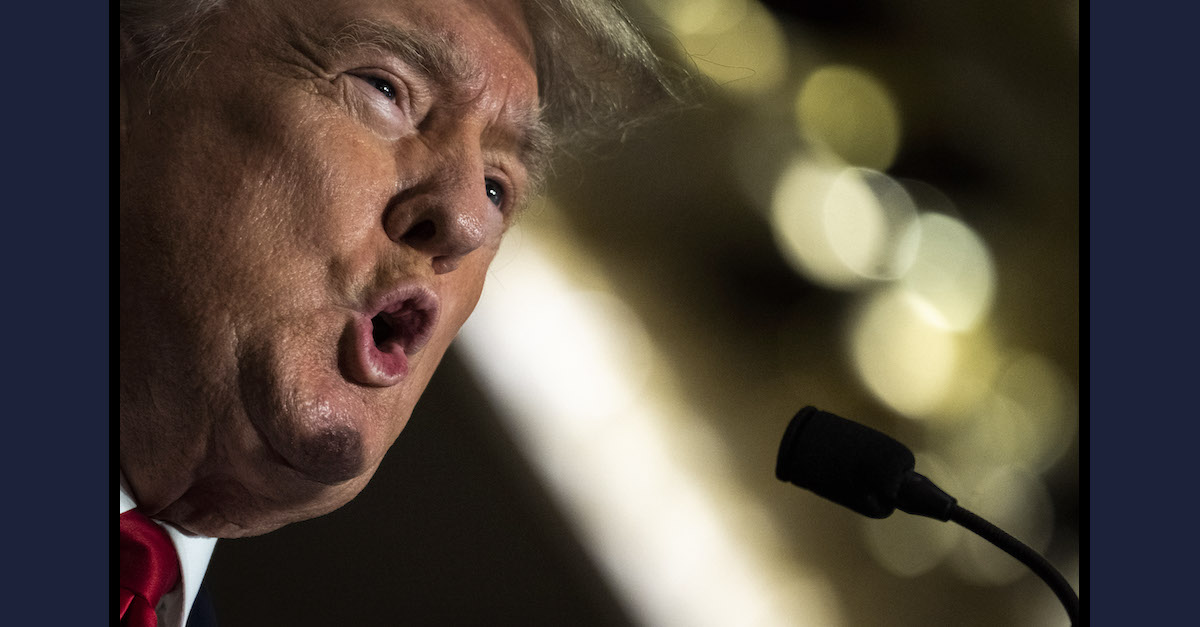

A file photo shows Donald Trump speaking on July 26, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.)

A letter unsealed Friday from Donald Trump attorney M. Evan Corcoran to the U.S. Department of Justice says the ex-president asserted “[n]o legal objection” to the transfer of some of the documents stored at Mar-a-Lago back to the government. But other documents that allegedly were retained at the compound were the subject of increasing government angst despite Corcoran’s assertion that one particular secrecy law didn’t pertain to Trump.

Corcoran’s May 25, 2022 letter was written to Jay I. Bratt, the chief of the counterintelligence and export control section of the National Security Division of the DOJ. While the letter asserts, in part, that certain document secrecy laws simply don’t apply to a former U.S. president, the DOJ’s own documents say federal authorities used other statutes to support their efforts to search Mar-a-Lago.

The convoluted case involves several sets of materials, and it is important to keep them straight. Fifteen boxes of documents from Mar-a-Lago were identified and requested in May 2021 by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) and the DOJ, according to a cache of court papers unsealed Friday. Twelve boxes were handed over by December 2021. Eventually, fifteen boxes were provided.

A warrant affidavit unsealed Friday says that the DOJ feared “additional” secret and classified documents remained at Mar-a-Lago after that allegedly cooperative transfer. That suspicion gave rise to an Aug. 5 search warrant, an Aug. 8 search, and the seizure of materials on the latter date.

“The communications regarding the transfer of boxes to NARA were friendly, open, and straightforward,” Corcoran wrote to Bratt in a passage which seeks to characterize Trump as cooperative when the initial spate of materials were returned to federal custody from the palatial Palm Beach, Florida compound. “President Trump voluntarily ordered that the boxes be provided to NARA. No legal objection was asserted about the transfer. No concerns were raised about the contents of the boxes. It was a voluntary and open process.”

The May 25 letter further indicates that the fifteen boxes in question were “unknowingly included among the boxes brought to Mar-a-Lago by the movers” after Trump exited the White House in January 2021.

Court documents say the DOJ’s belief that other sensitive materials remained at Trump’s post-presidential palazzo turned out to be true: the Aug. 8 seizure resulted in the recovery of secret, top secret, and confidential materials, some of which included SCI — or sensitive compartmented information. That’s according to an inventory of the fruits of the seizure filed in court.

While cautioning the DOJ to “not involve politics” in the matter back on May 25, Corcoran suggested that alleged DOJ leaks about the material were becoming nefarious given Trump’s penchant for remaining “active on the national political scene.”

Corcoran’s letter then claimed that Trump had “absolute authority to declassify documents” and that Trump’s “actions involving classified documents are not subject to criminal sanction.”

As to the former, Corcoran opined to Bratt that Trump enjoyed an “unfettered” ability to classify and declassify material due to his job. However, the letter does not directly assert that the documents in question were, indeed, declassified.

As to the latter, Corcoran maintained that “[a]ny attempt to impose criminal liability on a President or former President that involves his actions with respect to documents marked classified would implicate grave constitutional separation-of-powers issues.”

“Beyond that, the primary criminal statute that governs the unauthorized removal and retention of classified documents or material does not apply to the President,” he wrote (emphasis in the original).

Cited in support of that argument is the following federal statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1924(a):

Whoever, being an officer, employee, contractor, or consultant of the United States, and, by virtue ofhis office, employment, position, or contract, becomes possessed of documents or materials containing classified information of the United States, knowingly removes such documents or materials without authority and with the intent to retain such documents or materials at an unauthorized location shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for not more than five years, or both.

Corocoran asserted that the president was not “an officer . . . of the United States” and, “[t]hus, the statute does not apply to acts by a President.”

However, the FBI affidavit cited three other statutes — 18 U.S.C. §§ 793, 2071, and 1519 — as grounds for the search. None are the statute proffered by Corcoran to assert that Trump was above the laws other government actors are required to follow.

The trifecta of FBI-cited authorities have been known for days, but documents revealed Friday zeroed in on a subsection of sprawling § 793. The subsection noted by the government is §793(e), and it pertains to individuals with “unauthorized” possession, access, or control with regards to various forms of written materials involving national defense:

(e) Whoever having unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note relating to the national defense, or information relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit or cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted the same to any person not entitled to receive it, or willfully retains the same and fails to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it.

A footnote in the unsealed warrant affidavit illuminates the thinking of federal authorities as to the relevance of that subsection:

18 U.S.C. § 793(e) does not use the term “classified information,” but rather criminalizes the unlawful retention of “information relating to the national defense.” The statute does not define “information related to the national defense,” but courts have construed it broadly. See Gorin v. United States, 312 U.S. 19, 28 (1941) (holding that the phrase “information relating to the national defense” as used in the Espionage Act is a “generic concept of broad connotations, referring to the military and naval establishments and the related activities of national preparedness”). In addition, the information must be “closely held” by the U.S. government. See United States v. Squillacote, 221 F.3d 542, 579 (4th Cir. 2000) (”[I]nformation made public by the government as well as information never protected by the government is not national defense information.”); United States v. Morison, 844 F.2d 1057, 1071-72 (4th Cir. 1988). Certain courts have also held that the disclosure of the documents must be potentially damaging to the United States. See Morrison, 844 F.2d at 1071-72.

The affidavit, which is heavily redacted, suggests that Mar-a-Lago did not have the proper security measures in place to handle the material allegedly seized on Aug. 8.

Corcoran’s letter and the unsealed yet redacted search warrant affidavit are included here: