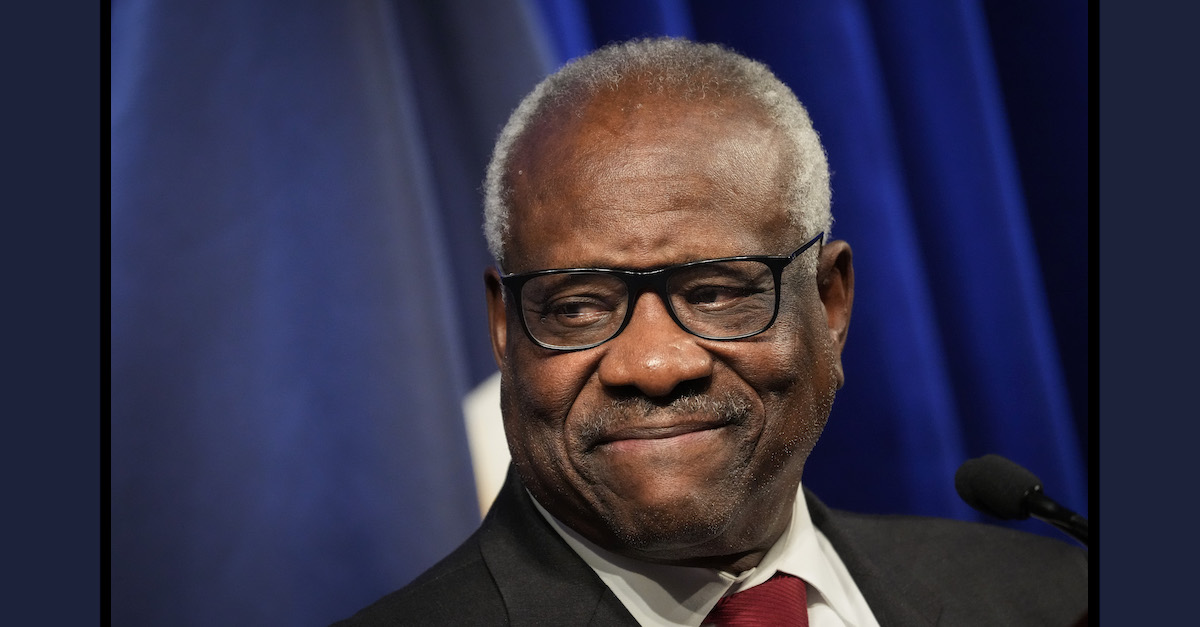

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas speaks at the Heritage Foundation on October 21, 2021 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.)

Led by Justice Clarence Thomas, the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday ruled 6-3 — and along typical ideological lines — that New York State’s “licensing regime” for handguns was unconstitutional.

Thomas was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Justice Stephen Breyer filed a dissent joined by Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The opinion extends the logic and reach of District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and McDonald v. Chicago (2010), two prior gun rights cases.

“[W]e recognized that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect the right of an ordinary, law-abiding citizen to possess a handgun in the home for self-defense,” Thomas wrote. “In this case, petitioners and respondents agree that ordinary, law-abiding citizens have a similar right to carry handguns publicly for their self-defense.”

The issue involved something more nuanced, however. The issue was whether New York could deny a handgun license to an individual citizen if the citizen did not show a “special need for self-defense.” That legal requirement in the Empire State, which the Court said was shared by six other states, went beyond the usual “objective criteria” that most other states use when determining whether a handgun license would be issued.

The Court concluded that the “special need for self-defense” requirement violated the Second Amendment.

“We too agree, and now hold, consistent with Heller and McDonald, that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual’s right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home,” Thomas wrote in broader terms.

Thomas noted that New York’s licensing mechanisms trace back about a hundred years. The distinction between the laws of most states and the challenged laws of New York and a minority of other states was discussed again later in the majority opinion:

New York is not alone in requiring a permit to carry a handgun in public. But the vast majority of States — 43 by our count — are “shall issue” jurisdictions, where authorities must issue concealed-carry licenses whenever applicants satisfy certain threshold requirements, without granting licensing officials discretion to deny licenses based on a perceived lack of need or suitability. Meanwhile, only six States and the District of Columbia have “may issue” licensing laws, under which authorities have discretion to deny concealed-carry licenses even when the applicant satisfies the statutory criteria, usually because the applicant has not demonstrated cause or suitability for the relevant license. Aside from New York, then, only California, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Jersey have analogues to the “proper cause” standard. All of these “proper cause” analogues have been upheld by the Courts of Appeals, save for the District of Columbia’s, which has been permanently enjoined since 2017.

The opinion did not immediately wipe away all handgun regulations as unconstitutional. It only questioned — and jettisoned — the “special need for self-defense” regulations discussed above; it did not deal with the “threshold requirements” necessary in “shall issue” jurisdictions.

Justice Kavanaugh (who was joined by Roberts) made the distinction between “objective” regulations and laws which grant “open-ended discretion” to licensing officials in a concurring opinion:

First, the Court’s decision does not prohibit States from imposing licensing requirements for carrying a handgun for self-defense. In particular, the Court’s decision does not affect the existing licensing regimes — known as “shall-issue” regimes — that are employed in 43 States. The Court’s decision addresses only the unusual discretionary licensing regimes, known as “may-issue” regimes, that are employed by 6 States including New York. As the Court explains, New York’s outlier may-issue regime is constitutionally problematic because it grants open-ended discretion to licensing officials and authorizes licenses only for those applicants who can show some special need apart from self-defense. Those features of New York’s regime — the unchanneled discretion for licensing officials and the special-need requirement — in effect deny the right to carry handguns for self-defense to many “ordinary, law-abiding citizens.”

[ . . . ]

New York’s law is inconsistent with the Second Amendment right to possess and carry handguns for self-defense

The majority opinion also rubbished a test employed by many lower courts when examining gun restrictions. In articulating a way to move forward, the majority held that the lower courts must refocus their analyses on the “Nation’s history and tradition” of gun rights. Again, from the majority opinion:

In Heller and McDonald, we held that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual right to keep and bear arms for self-defense. In doing so, we held unconstitutional two laws that prohibited the possession and use of handguns in the home. In the years since, the Courts of Appeals have coalesced around a “two-step” framework for analyzing Second Amendment challenges that combines history with means-end scrutiny.

Today, we decline to adopt that two-part approach. In keeping with Heller, we hold that when the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. To justify its regulation, the government may not simply posit that the regulation promotes an important interest. Rather, the government must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only if a firearm regulation is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

A footnote digs into that issue further by taking a swipe at Justice Breyer’s dissent:

Rather than begin with its view of the governing legal framework, the dissent chronicles, in painstaking detail, evidence of crimes committed by individuals with firearms. [Citation omitted.] The dissent invokes all of these statistics presumably to justify granting States greater leeway in restricting firearm ownership and use. But, as Members of the Court have already explained, “[t]he right to keep and bear arms . . . is not the only constitutional right that has controversial public safety implications.” McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U. S. 742, 783 (2010) (plurality opinion).

“Our holding decides nothing about who may lawfully possess a firearm or the requirements that must be met to buy a gun,” Justice Alito wrote in a concurrence. “Nor does it decide anything about the kinds of weapons that people may possess.”

Alito also criticized Justice Breyer’s dissent by pointing to the massacre of 10 people, all of them Black, in Buffalo, New York on May 14 — a matter cited by Breyer. Three victims survived, two of whom were white.

Per Justice Alito (citations to the record are omitted):

Why, for example, does the dissent think it is relevant to recount the mass shootings that have occurred in recent years? Does the dissent think that laws like New York’s prevent or deter such atrocities? Will a person bent on carrying out a mass shooting be stopped if he knows that it is illegal to carry a handgun outside the home? And how does the dissent account for the fact that one of the mass shootings near the top of its list took place in Buffalo? The New York law at issue in this case obviously did not stop that perpetrator.

Alito then questioned why Breyer discussed “statistics about the use of guns to commit suicide.”

During oral arguments in the case, Alito complained that “all these people with illegal guns,” including people “on the subway” and “walking around the streets,” were carrying weapons with impunity, but “ordinary, hard-working, law-abiding people” were being stymied by the state, in his view.

“They can’t be armed,” Alito said of those who wished to have lawfully obtained guns for self-protection.

During oral arguments, Thomas tipped his hand at what would eventually become part of the key holding.

“If we are to analyze this based upon the history or tradition, should we look at the founding, or should we look at the time of the adoption of the 14th Amendment?” he asked.

The answer, the Supreme Court suggested on Thursday, is that the “history and tradition” analysis should probably focus narrowly on the time the Second Amendment was adopted — but the Court said it “need not address this issue today because . . . the public understanding of the right to keep and bear arms in both 1791 and 1868 was, for all relevant purposes, the same with respect to public carry.”

Again, from the majority opinion:

“Constitutional rights are enshrined with the scope they were understood to have when the people adopted them.” Heller, 554 U. S., at 634–635 (emphasis added). The Second Amendment was adopted in 1791; the Fourteenth in 1868. Historical evidence that long predates either date may not illuminate the scope of the right if linguistic or legal conventions changed in the intervening years.

After scads of pages of historical examples, the Court came to this conclusion, which is far from an unfettered stance on the Second Amendment:

To summarize: The historical evidence from antebellum America does demonstrate that the manner of public carry was subject to reasonable regulation. Under the common law, individuals could not carry deadly weapons in a manner likely to terrorize others. Similarly, although surety statutes did not directly restrict public carry, they did provide financial incentives for responsible arms carrying. Finally, States could lawfully eliminate one kind of public carry—concealed carry—so long as they left open the option to carry openly.

None of these historical limitations on the right to bear arms approach New York’s proper-cause requirement because none operated to prevent law-abiding citizens with ordinary self-defense needs from carrying arms in public for that purpose.

Justice Breyer’s dissent began by pointing out that “[i]n 2020, 45,222 Americans were killed by firearms.”

“Since the start of this year (2022), there have been 277 reported mass shootings — an average of more than one per day,” Breyer continued. “Many States have tried to address some of the dangers of gun violence just described by passing laws that limit, in various ways, who may purchase, carry, or use firearms of different kinds. The Court today severely burdens States’ efforts to do so.”

Breyer’s dissent contained a lengthy list of violent mass shootings to make its point. He also reframed the issue SCOTUS was asked to decide.

“The question before us concerns the extent to which the Second Amendment prevents democratically elected officials from enacting laws to address the serious problem of gun violence,” Breyer posited. “And yet the Court today purports to answer that question without discussing the nature or severity of that problem.”

“[T]he Court wrongly limits its analysis to focus nearly exclusively on history,” Breyer said elsewhere as to the actual machinations of the majority ruling. “It refuses to consider the government interests that justify a challenged gun regulation, regardless of how compelling those interests may be. The Constitution contains no such limitation, and neither do our precedents.”

Breyer continued:

In my view, when courts interpret the Second Amendment, it is constitutionally proper, indeed often necessary, for them to consider the serious dangers and consequences of gun violence that lead States to regulate firearms. The Second Circuit has done so and has held that New York’s law does not violate the Second Amendment. See Kachalsky v. County of Westchester, 701 F. 3d 81, 97–99, 101 (2012). I would affirm that holding. At a minimum, I would not strike down the law based only on the pleadings, as the Court does today — without first allowing for the development of an evidentiary record and without considering the State’s compelling interest in preventing gun violence. I respectfully dissent.

Read the full opinion below:

This report, which began as a developing story, has been updated several times since its initial publication to include more detail from the Court’s opinion.