Jennifer Crumbley, Ethan Crumbley, and James Crumbley appear in mugshots taken by the jail in Oakland County, Mich., in December 2021.

In an effort to avoid civil liability after a mass shooting, Michigan’s Oxford Community Schools on Friday legally blamed alleged murderer Ethan Crumbley and his parents for a November 2021 massacre that left four dead and seven injured.

According to a “notice of non-party fault” filed in federal court, defense lawyers pointed the finger at Crumbley and his parents, James Crumbley and Jennifer Crumbley, in one of several civil lawsuits filed against the district and its staff. The lawsuit — and others like it — are aimed at the school’s alleged transgressions in handling the teen just before he allegedly pulled the trigger.

“Defendants contend that the conduct complained of by Plaintiffs was proximately caused or contributed to by said individuals,” according to the brief document from lawyers for Oxford Community Schools.

The document mirrors a similar filing from January.

The $100 million lawsuit which prompted the blaming of the parents was filed by Jeffrey Franz and Brandy Franz on behalf of their children Riley Franz, 17, and Bella Franz, 14, in early December — just days after the Nov. 30, 2021 shooting spree.

Geoffrey N. Fieger, who is representing the Franz family, referred to Ethan Crumbley’s parents as “poster children for the Second Amendment gun nuts” during a Thus., Dec. 9, 2021 news conference about the Oxford High School shooting in Michigan. (Images via screengrab from WZZM-TV/YouTube.)

Riley Franz was shot in the neck, the lawsuit says, “as a direct result of” acts by the district and its administrators, “causing her severe trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, fright, shock, terror, anxiety as well as physical and emotional injuries.”

Bella Franz, meanwhile, “narrowly escaped the bullets discharged towards her, her sister, and her friends,” the lawsuit alleges. “She observed her sister, friends and classmates being shot and murdered, causing her severe trauma, fright, shock, terror, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and emotional injuries.”

The named defendants include several school administrators, including the district’s now-former superintendent and the principal of the high school where the shooting occurred. Several similar civil lawsuits have also been filed by other victims.

The civil lawsuits generally allege that the school district failed to recognize days of warning signs that Ethan Crumbley presented an extreme risk of violence. The lawsuits also generally allege that the school was responsible for myriad torts by allowing Crumbley to return to the general student population after he allegedly drew violent drawings on a math assignment — drawings which prompted him to be removed from a classroom. Some of the lawsuits say the district failed to adhere to its own policies when administrators failed to search Crumbley’s backpack in light of the drawings.

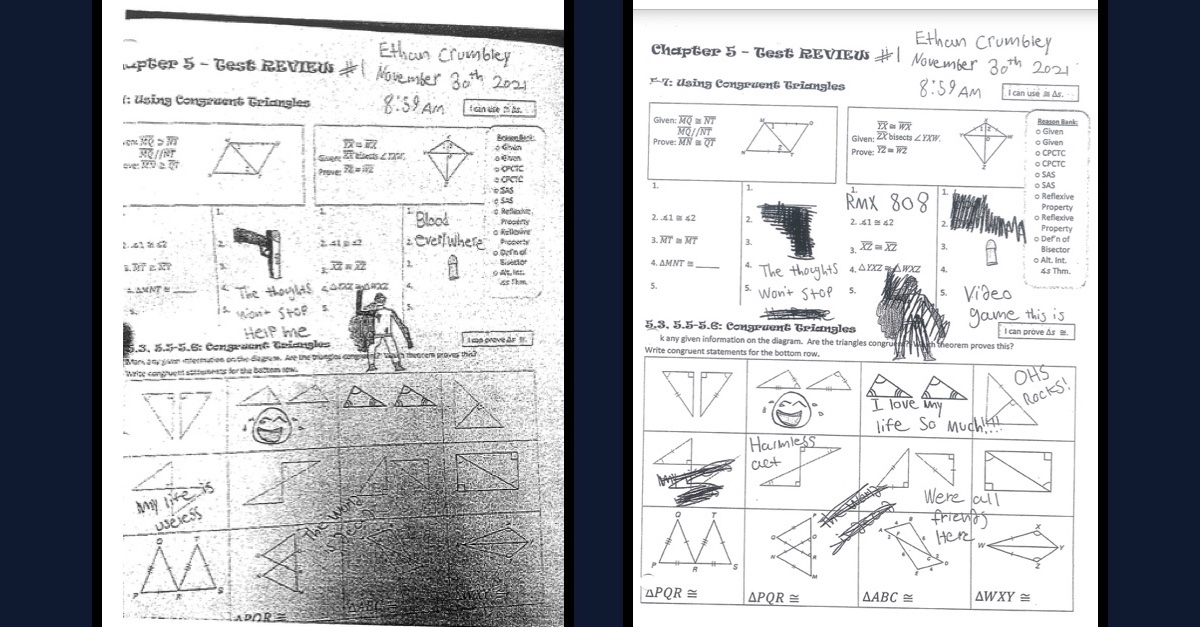

Court records contain copies of images allegedly drawn by Ethan Crumbley before he allegedly shot and killed four people at Oxford High School. The image on the left is said by prosecutors to portray a photo of the original drawings; the image on the right depicts how the drawings were allegedly scratched out and modified by Crumbley after a teacher caught him.

Law&Crime has previously reported the accusations lodged by the Franz family in detail.

The district responded to those accusations in another document filed Friday. The point-by-point answer to the plaintiff’s second amended complaint is, in broad terms, a blanket denial of liability as to the facts and as to the law. It asserts that the introductory “allegations” in the Franz lawsuit “are denied for the reason that they are untrue as to factual representation and contain incorrect and erroneous conclusions of law.”

In a further point-by-point denial, the school district said it would “neither admit nor deny” that the “actions alleged . . . took place within Oakland County, State of Michigan.”

In one section of the reply (paragraph 11), the district refused to admit or deny that Riley and Bella Franz were students, but in another area (paragraphs 23 and 24) it did agree that they were, indeed, pupils.

The district further refused to admit or deny that it was a “municipal corporation, duly organized” or that it carried out “functions” such as “organizing, teaching, operating, staffing, training, and supervising the staff, counselors, and teachers at Oxford High School” (paragraph 13).

In other paragraphs (e.g., 30 and 31), the district neither admitted nor denied the contents of its own website and Code of Conduct.

A memorial outside Oxford High School in early December 2021 contained pictures of shooting victims Hana St. Juliana, 14, Madisyn Baldwin, 17, Tate Myre, 16, and Justin Shilling, 17. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.)

Some other paragraphs cut closer to the core issue of liability. For instance, here’s the verbiage of the original lawsuit:

35. Upon information and belief, in the days leading up to the November 30, 2021, incident, Ethan Crumbley acted in such a way that would lead a reasonable observer to know and/or believe that he was planning to cause great bodily harm to the students and/or staff at Oxford High School.

36. By way of example, and not limitation, previous to the November 30, 2021, incident, Ethan Crumbley posted countdowns and threats of bodily harm, including death, on his social media accounts, warning of violent tendencies and murderous ideology prior to actually coming to school with the handgun and ammunition to perpetuate the slaughter.

From the response:

35. In answer to paragraph 35, Defendants deny the allegations for the reason that the allegations are untrue.

36. In answer to paragraph 36, Defendants deny the allegations contained therein for the reason that they are untrue.

The district further would “neither admit nor deny” that “on November 11, 2021, Ethan Crumbley brought a severed bird head in a mason jar containing a yellow liquid to Oxford High School and left the jar on a toilet paper dispenser in the boys bathroom” (paragraph 38).

A memorial outside of Oxford High School was photographed on Dec. 3 2021 in Oxford, Michigan. Four students were killed and seven others injured on November 30, when student Ethan Crumbley allegedly opened fire with a pistol at the school. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.)

The district did, however, flatly deny the following paragraphs (40 and 41) in the second amended complaint and asserted flatly that both were “untrue.”

40. The following day, on November 12, 2021, the Oxford High School administration sent an email to parents of Oxford High School students indicating, “Please know that we have reviewed every concern shared with us and investigated all information provided . . . [w]e want our parents and students to know that there has been no threat to our building nor our students.”

41. On or about November 16, 2021, days prior to the actual incident, multiple parents of students provided communications to Defendant WOLF with concerns about threats to students made on social media, and the incident of the severed animal heads at Oxford High School, the two weeks before.

The response filing by the defendants elsewhere denied that several administrators had reviewed Crumbley’s social media posts prior to the shooting, denied that administrators had “actual knowledge of concerns from parents” about threats on campus, denied that they knew Crumbley allegedly brought the severed bird’s head to school, denied that administrators knew of “Crumbley’s violent tendencies and ideations,” denied sending “correspondence and emails to parents” that asserted that the “children were safe” in the days before the shooting, and denied telling people to “stop reporting, sharing, or otherwise discussing” threatening material.

Elsewhere, the district and its staff, via their attorneys, denied the allegations that Crumbley brought live ammunition to the school and “openly displayed” it in a classroom on Nov. 29, denied that Crumbley was “searching for ammunition on his cell phone during class” on that same date, and denied that one administrator “left a voicemail” for Jennifer Crumbley “regarding Ethan Crumbley’s inappropriate internet search.”

Further on, the defendants denied that a teacher “observed Ethan viewing violent videos of shootings and notified” administrators by email of what was occurring.

The defendants then denied that a teacher caught Crumbley drawing “horrific images” on his math assignment — something criminal prosecutors and the plaintiffs have long alleged. Here’s the original accusation from the civil suit (paragraph 90):

On the morning of November 30, 2021, Defendant ALLISON KARPINSKI discovered horrific drawings on assignments left on Ethan Crumbley’s desk, after Ethan was caught searching for and watching violent shooting videos on his phone. These horrific writings and drawings, and Ethan’s watching of shooting videos, were reported to Defendant EJAK and Defendant SHAWN HOPKINS. Defendant MORGAN took a picture of said note with her cell phone.

“[T]hey are untrue,” the lawsuit said in response while denying the paragraph’s assertions in whole cloth fashion.

Hopkins testified in a pretrial criminal hearing in late February that Crumbley claimed to have been watching violent video games in class. Hopkins said he discussed the violent drawings with Crumbley directly and asked the teen’s parents to pick Ethan up from school to take him home.

The defendants — that is, the district and several named employees — further denied that they had made a “knowing and deliberate decision to leave, unsearched, Ethan Crumbley’s backpack, even after discovering the alarming note authored by Crumbley.” And, accordingly, the defendants denied that administrator Nicholas Ejak “brought him [Crumbley] his backpack without searching it” after Crumbley had been brought to the office but before the shooting.

The defendants further denied threatening to call Child Protective Services if Crumbley’s parents did not seek counseling for Crumbley “within 48 hours” of when he was allegedly caught making the violent drawings.

Hopkins testified that he did, however, have communications with the Crumbley parents on this topic.

“I want him seen within 48 hours,” Hopkins testified that he told Jennifer Crumbley. “I will be following up.”

In criminal court proceedings, Crumbley’s parents have contested that narrative; their attorneys have said they were given the “option” to leave Ethan in school and, ergo, assumed that the school had things under control.

As to a paragraph (119), which described the ensuing shooting as a “massacre,” this school district paused its usual drumbeat of unknowingness or blanket denial to state the following:

Defendants further state that its ALICE [active shooter] emergency response to the situation presented on November 30 saved lives. Oxford High School administration, including Principal Steve Wolf, Kristy Gibson-Marshall, and Kurt Nuss ran toward the incident, unarmed, to effectively save children, administer aid to injured parties, and to locate the perpetrator, putting themselves in harm’s way.

The defendants then asserted a broad collection of affirmative defenses to the allegations:

Defendants affirmatively state that they were guided by and strictly observed all legal duties and obligations imposed by operation of law and otherwise. Further, all actions of their agents, servants and/or employees were careful, prudent, proper and lawful.

[ . . . ]

Defendants were engaged in the performance of governmental functions and, therefore, are immune from suit for civil damages for this claim pursuant to the principles of governmental immunity as set forth in case law and the statutes of this State.

The defendants also said they were protected by the doctrine of qualified immunity.

“Defendants are not liable to Plaintiffs for the criminal, assaultive acts of third parties,” they also posited.

Plus, they said, “Plaintiffs’ claim is barred by the Michigan Revised School Code.”

“Plaintiffs’ claim fails as a matter of law and fact because Defendants were not required to protect Plaintiffs from the violence or other mishaps that are not directly attributable to the conduct of its employees,” the affirmative defenses continued.

The defense reply asked the judge overseeing the matter to “enter an order of no cause of action as to Defendants, together with costs and attorney fees so wrongfully sustained.” In other words, the school district and the other individual defendants want the victims of the shooting to pay for, in their opinion, erroneously dragging the case into the courthouse at all.

Ethan Crumbley is accused in the state’s criminal courts of murdering Hana St. Juliana, 14, Tate Myre, 16, and Madisyn Baldwin, 17, on the day of the shooting; he’s also charged with murdering Justin Shilling, 17, who died the morning after the attack. Crumbley’s parents are criminally charged with involuntary manslaughter.

Read the second amended complaint, the reply, and the notice of non-party fault below: