A memorial outside of Oxford High School was photographed on Dec. 3 2021 in Oxford, Michigan. Four students were killed and seven others injured on November 30, when student Ethan Crumbley allegedly opened fire with a pistol at the school. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.)

The mother of a student who died during a mass shooting at Oxford High School in Oakland County, Michigan last year has filed a federal civil lawsuit against the school district and some of its administrators. The lawsuit is one of two filed on Wednesday in connection with the shooting. Several other victims have sued previously.

Ethan Crumbley is accused of murdering Hana St. Juliana, 14, Tate Myre, 16, and Madisyn Baldwin, 17, on the day of the shooting; he’s also charged with murdering Justin Shilling, 17, who died the morning after the Nov. 30, 2021 attack. Crumbley’s parents are charged with involuntary manslaughter.

A memorial outside Oxford High School in early December 2021 contained pictures of shooting victims Hana St. Juliana, 14, Madisyn Baldwin, 17, Tate Myre, 16, and Justin Shilling, 17. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images.)

Baldwin’s mother, Nicole Beausoleil, filed one of the two cases on Wednesday against the school district. Also named as defendants are now-former Superintendent Timothy Throne, Principal Steven Wolf, Dean of Students Nicholas Ejak, and school counselor Shawn Hopkins.

Nicole Beausoleil, mother of Oxford HS shooting victim, Madisyn Baldwin, has filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the school district and four employees, following the November 30th shootings. Also named were Oxford Superintendent, Tim Throne, and Principal, Steven Wolf. pic.twitter.com/dhGWsc0KQn

— Jon Hewett (@JonHewettWWJ) June 8, 2022

The lawsuit begins by pointing to myriad mass shootings in other schools — Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Parkland — and to the myriad training sessions school officials have undertaken in order to stop school violence. The lawsuit alleges those trainings and policies were not followed in Michigan.

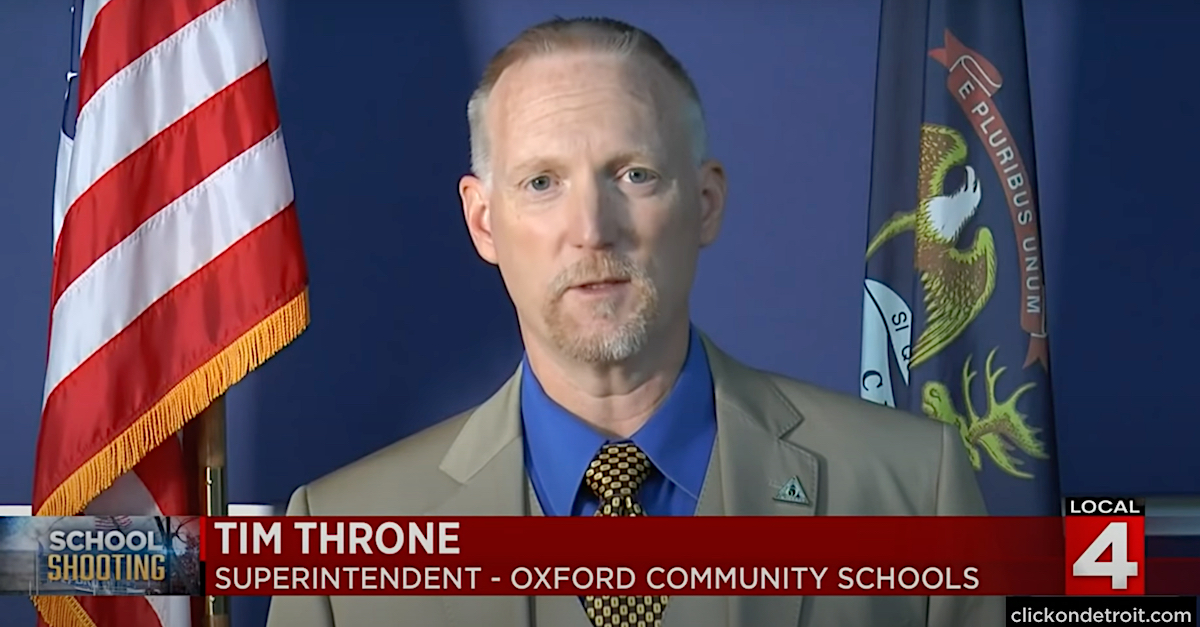

Oxford School Superintendent Tim Throne appeared in a Dec. 2, 2021 recorded message to the public after the Oxford High School shooting. (Image via YouTube screengrab/WDIV-TV.)

“The purpose of such extensive training and education is to teach school administrators and staff that such actions are not the result of ‘random acts of violence’; instead, they are predictable and preventable,” the lawsuit asserts.

Oxford Principal Steven Wolf recorded a Jan. 23, 2022 “welcome back” message for students. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

The lawsuit refers to Crumbley only by his initials:

Tragically, on November 30, 2021, school officials and administrators at Oxford High School ignored their training and took affirmative actions, in accordance with school policy, to remove a mentally unstable student, 15-year-old E.C., from a place of safety in the school counselor’s office and return him to the school population, despite his obvious suicidal and homicidal ideations and access to weapons.

The unfathomable violence that occurred on November 30, 2021, took the lives of four students, including Madisyn Baldwin, 17, and injured seven other individuals, including a teacher. The school shooting was both predictable and preventable.

School counselor Shawn Hopkins testified on Feb. 24, 2022, during a preliminary hearing for James and Jennifer Crumbley, the parents of Ethan Crumbley. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

The lawsuit says Crumbley “became known to school staff, including teachers, counselors, and administrators, as a child who may be suffering from mental illness and/or child abuse and neglect, given his outwardly depressed mood and disheveled appearance.” It then presents a laundry list of warning signs that administrators allegedly refused to take seriously.

16. In early November, E.C.’s Spanish teacher emailed Defendant, HOPKINS, that E.C. seemed “sad.” HOPKINS contacted E.C. and told him he was available if E.C. wanted to talk to somebody. E.C. simply responded, “Okay.”

17. On or about November 11, students found the severed head of a bird in a boys’ bathroom. It was reported to Defendant, WOLF.

18. WOLF chose not to disclose this incident to school staff or parents.

19. On November 12, OCSD administrators sent an email to Oxford High School parents, stating, “We are aware of the numerous rumors that have been circulating throughout our building this week …. Please know that we have reviewed every concern shared with us and investigated all information provided …. We want our parents and students to know that there has been no threat to our building nor our students.”

20. On or around November 16, Defendant, WOLF, was informed by several parents that there were threats made to students at Oxford High School on social media, as well as concerns over severed animal heads at the school.

21. Instead of investigating these threats, which caused several students to be afraid for their safety at school, OCSD administrators, including Defendant, WOLF, blithely ignored the threats.

22. On November 16, WOLF emailed parents, stating, “I know I’m being redundant here, but there is absolutely no threat here at the HS . . . large assumptions were made from a few social media posts, then the assumptions evolved into exaggerated rumors.”

23. On November 16, Defendant, THRONE, took to the Oxford HS loudspeaker and told students that there was no credible threat to their safety.

Jennifer Crumbley, Ethan Crumbley, and James Crumbley appear in mugshots taken by the jail in Oakland County, Mich., in Dec. 2021.

In the ensuing days, the lawsuit notes, Crumbley’s “parents bought him a Sig Sauer 9 mm, semi- automatic handgun as an early Christmas gift.” Then came additional red flags, the lawsuit alleges:

27. On November 29, E.C.’s Spanish teacher emailed Defendant, EJAK, and Pam Fine, OCSD’s Restorative Practices Coordinator, telling them that E.C. had been using his cell phone during class to look up information about bullets.

28. The email was forwarded to Defendant, HOPKINS, E.C.’s counselor.

29. At about 9:00 that morning, E.C. was summoned to Ms. Fine’s office for a meeting with Fine and HOPKINS. The meeting only lasted five minutes.

30. During the short meeting, E.C. was informed that looking up bullets while in school was not “school appropriate behavior.”

31. In response, E.C. informed HOPKINS and Fine that he had gone to a gun range with his mother over the weekend and tested out his new handgun. He claimed that he was simply researching information about bullets because shooting guns was his hobby.

32. E.C. was returned to class. Fine then called E.C.’s mother and left her a voicemail message. Per OCSD policy, E.C.’s mother was not required to return the call, as the incident had not been deemed a “disciplinary incident.”

33. On November 29, E.C. posted on his public Twitter account, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds. See you tomorrow Oxford.”

The lawsuit then recaps the events of November 30, the day of the shooting: Crumbley was caught “watching a violent shooting video on his cell phone during class hours,” he got caught drawing an “extremely disturbing” shooting scene on a math worksheet; he then allegedly scratched out some of the drawings to cover them up. But, according to the lawsuit, the administrative failures continued unabated until death and destruction ensued:

37. EJAK advised HOPKINS of the drawings he had seen. HOPKINS went to E.C.’s class and took him to the counseling office.

38. EJAK then went to the math classroom and found E.C.’s backpack. He took the backpack to the counseling office.

39. In handling the backpack, EJAK could tell that the backpack was unusually heavy for a school backpack and that the weight was not evenly distributed as a backpack would be if filled with books.

40. The weight and distribution were unusual because the backpack was filled with a Sig Sauer 9 mm metal handgun and 48 bullets.

Despite allegedly recognizing that Crumbley was homicidal and suicidal, administrators only threatened to call child protective services workers on his parents if they refused to seek immediate counseling, the lawsuit says.

58. HOPKINS turned to EJAK and asked whether there was any disciplinary issue that would prevent E.C. from returning to class. When EJAK responded, “No,” HOPKINS told the parents, “I guess we are done.”

59. The threat about contacting CPS had the clear and obvious effect of accelerating E.C.’s already rapidly deteriorating mental health.

[ . . . ]

61. EJAK and HOPKINS deliberately chose not to search E.C.’s backpack (or locker), despite a Michigan statute stating that a student has no expectation of privacy in a backpack or locker.

From there, Crumbley was returned to the general student population, and from there, he went on to commit mass murder, the lawsuit alleges. Ejak and Hopkins, the lawsuit claims, did not involve the school resource officer, who would have searched Crumbley’s backpack for weapons.

The lawsuit alleges three counts: (1) state-created danger by Ejak and Hopkins under the 14th Amendment, (2) Monell liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 by the school district; and (3) gross negligence by Throne, Wolf, Ejak, and Hopkins.

The lawsuit seeks wrongful death damages allowable under Michigan law; past and future compensatory damages; punitive damages; unreimbursed medical, burial, and funeral expenses; “[c]onscious pain and suffering experienced by Madisyn Baldwin after being shot,” and the loss of companionship suffered by Baldwin’s family.

The shooting occurred the next day, and the facts are recounted in the court papers.

Shooting survivor Kylie Ossege also filed a federal civil lawsuit Wednesday against the same named defendants: the school, Throne, Wolf, Ejak, and Hopkins. Ossege’s lawsuit makes substantially similar accusations as the Beausoleil lawsuit, but it adds additional alleged failures to enforce or apply school policy:

68. Pursuant to the Suicide Intervention Process, staff members are required to “converse with the student immediately to determine if s/he has dangerous instrumentalities (weapon, substance, or other material capable of inflicting a mortal wound) on or nearby his/her person.”

69. Ejak and Hopkins never asked EC if he had a weapon on or nearby his person.

[ . . . ]

73. Where a student “is in imminent danger of harming himself” the Suicide Intervention Process requires the staff member to contact an outside agency “immediately, give them the facts, request them to intervene, and follow their instructions.”

74. If the agency declines to intervene before the end of the school day, the staff member is required to call the “emergency squad.”

75. Neither Ejak or Hopkins contacted any outside agencies. They did not request intervention by any outside agency and they did not contact the “emergency squad.”

The lawsuit also alleges that administrators left Crumbley alone while suicidal in violation of other cited school policies.

Ossege alleges six counts: (1) state-created danger; (2) supervisory liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; (3) Monell liability; (4) violations of Michigan’s Child Protection Law; (5) gross negligence; and (6) violations of Article 1, § 17 of the 1963 Michigan Constitution. Not every count is alleged against every defendant.

Ossege seeks compensation for the following damages: “past and future medical expenses, emotional distress, physical and emotional pain and suffering, fright and shock, loss of earning capacity, reasonable expenses for caretaking, mental health services and emotional support dog, and the loss of the ordinary pleasures of life.”

Other civil suits have also been filed in connection with the massacre. Hana St. Juliana’s family sued earlier this year; so did the family of Tate Myre. The parents of two surviving students sued last December just days after the shooting. A federal judge on Tuesday agreed to dismiss a single defendant from the latter lawsuit. That defendant, Ryan Moore, was referred to as the high school’s “Dean of Students”; however, defense attorneys said he was actually working in another building under a different job title when the shooting occurred.

Copies of both lawsuits are embedded below: