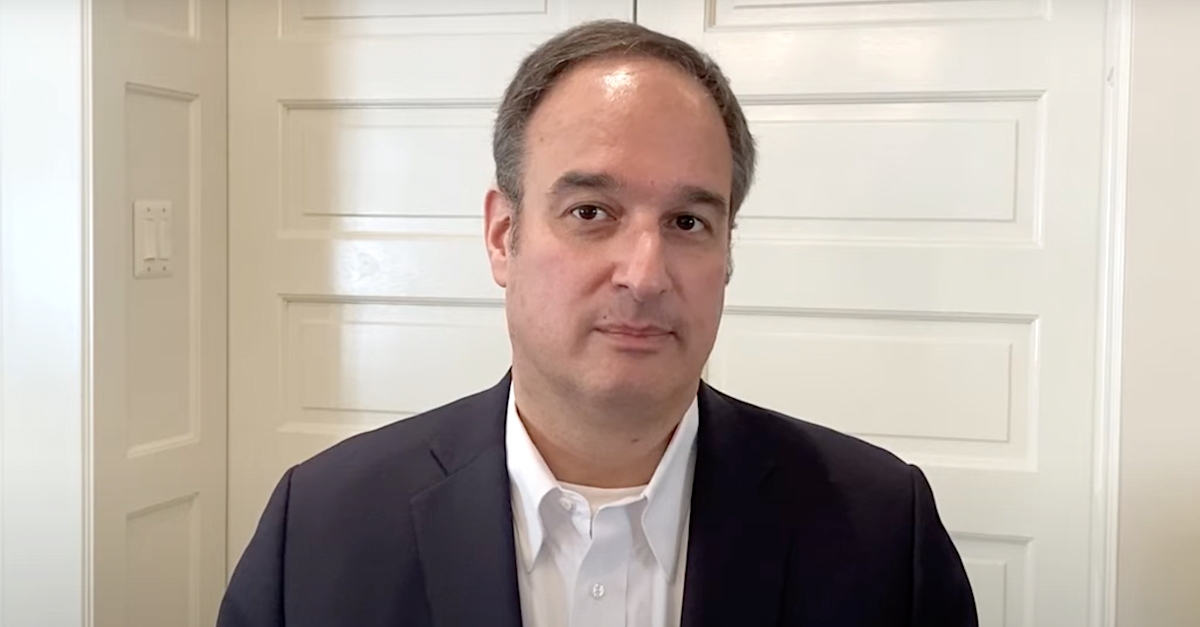

Michael Sussmann.

A federal judge on Wednesday agreed to keep a criminal case alive against a former Perkins Coie attorney who worked on Hillary Clinton matters in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election. The attorney claimed that he was acting as a private citizen when giving data about Donald Trump to then-FBI General Counsel James A. Baker on Sept. 19, 2016.

That indicted lawyer, Michael A. Sussmann, is charged with a single count of making a false statement to the FBI in connection with his assertion that he was not acting on behalf of any Democratic Party-tied client when he provided a tip about then-presidential candidate Donald Trump and Russia’s Alfa Bank. It turned out there was no real connection between the two, and federal prosecutors are not directly litigating whether the underlying tip itself was true; the issue is the alleged assertion that Sussmann wasn’t working for a rival candidate.

Sussmann was indicted at the behest of Special Prosecutor John H. Durham, who was appointed by then-Attorney General William Barr to suss out the roots of “whether any federal official, employee, or any other person or entity violated the law in connection with . . . law-enforcement activities directed at the 2016 presidential campaigns.”

U.S. District Judge Christopher R. Cooper, via a six-page opinion and order, ruled against Sussmann’s attempt to dismiss the matter in the weeks prior to trial.

“The Indictment claims that Sussmann concealed from Baker that he was providing the information to the FBI in a political capacity,” Judge Cooper wrote while recapping the core case. “Specifically, Sussmann allegedly told Baker that he was not attending the meeting on behalf of any client when, in fact, he had assembled and was conveying the information on behalf of two specific clients: (1) a technology-industry executive named Rodney Joffe and (2) the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign. The FBI opened an investigation based on the information Sussmann provided, but ultimately determined that there was insufficient evidence to support the existence of a communication channel between the Trump campaign and the Russian bank.”

Sussmann has long argued that (1) he did not lie to the FBI, and (2) that, even if he lied, his alleged lie was not “material” to whether or not the FBI opened a probe regarding Trump based on the information provided.

Despite those arguments, Judge Cooper said that the case must stay alive because “Supreme Court unanimously held that because materiality is an element of a § 1001 offense” and, therefore, “it is a question that generally must be answered by a jury.”

Judge Cooper ruled that he thus could not dismiss the matter before it even goes before a jury: “[t]he battle lines thus are drawn, but the Court cannot resolve this standoff prior to trial.”

As noted, the case turns on whether or not Sussmann’s alleged lie was “material” to the FBI’s decision-making process regarding the tip received.

“For a statement to be criminal under 18 U.S.C. § 1001, it must be both ‘false, fictitious, or fraudulent’ and ‘material,'” Judge Cooper wrote. He went on to explain:

The standard for materiality under § 1001 in this circuit is whether the statement has “a natural tendency to influence, or is capable of influencing, either a discrete decision or any other function of the [government] agency to which it was addressed.” United States v. Moore, 612 F.3d 698, 701 (D.C. Cir. 2010). Focusing on the first part of the standard, Sussmann argues that his alleged statement to Baker—that he was not at the meeting on behalf of a client—could not possibly have influenced what was, in his view, the only “discrete decision” before the Bureau at the time: whether to initiate an investigation into the Trump campaign’s asserted communications with the Russian bank.

Sussmann wanted the inquiry focused “only” on the “FBI’s decision to commence an investigation” based on the data he provided. That, Judge Cooper rationed, was a myopic view of the law — one “based on an overly narrow conception of the applicable standard.”

Specially, Sussmann’s argument “largely ignores the second part of the test: whether the statement could influence ‘any other function’ of the agency,” the judge ruled. “Applying that prong of the materiality standard, the D.C. Circuit has stated that a ‘lie distorting an investigation already in progress’ also would run afoul of § 1001.”

“As the Special Counsel argues, it is at least possible that statements made to law enforcement prior to an investigation could materially influence the later trajectory of the investigation,” Judge Cooper continued. “Sussmann offers no legal authority to the contrary.”

In both a footnote and in the body of his main opinion, Judge Cooper accused Sussmann’s lawyers of stretching the meaning of case law beyond that which the court could countenance. The judge said some of the materials cited by the defendant and his legal team “deal with entirely different circumstances” than the issue at hand.

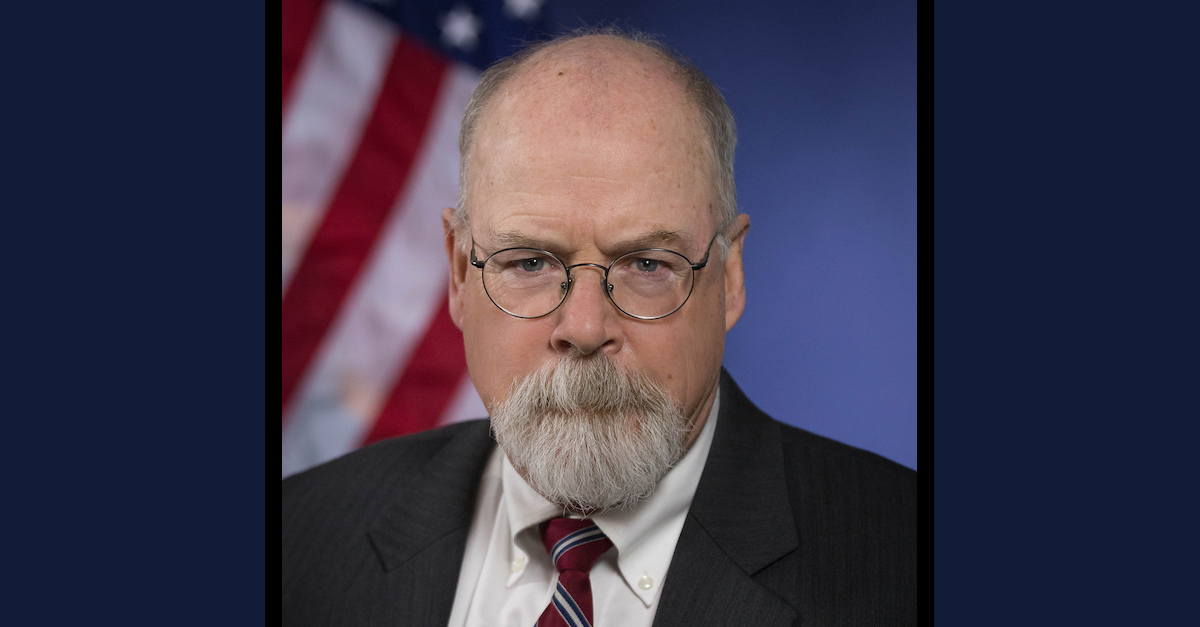

John Durham.

Judge Cooper further noted that Durham’s team hopes to prove that, had Sussmann been (allegedly) more forthright about his connections to the Democrats and to Clinton, the FBI might have engaged in “further questions” or “taken additional or more incremental steps before opening and/or closing an investigation.” In other words, per Durham, Sussmann would have been viewed by the FBI with significant skepticism had his connections to the Democrats been disclosed fully and completely. Or, in other words, the unsubstantiated claims that Trump was communicating with Russia may have gasped for air or perhaps even died in the halls of the FBI rather than being spread publicly just prior to the election.

Cooper grappled with the special prosecutor’s theory at length:

For his part, the Special Counsel resists the notion that the FBI faced a binary choice — i.e., to open a “full investigation” or not — in deciding how to respond the information Sussmann conveyed. He anticipates evidence at trial will show that the Bureau could have instead taken a number of incremental steps, including conducting a less formal “assessment” of the information, initiating a “preliminary investigation,” or delaying a decision until after the election. And “had [Sussmann] truthfully informed Baker that he was providing the information on behalf of one or more clients,” the Special Counsel claims, “[Baker] and other FBI personnel might have asked a multitude of additional questions material to the case initiation process.” According to the Special Counsel, those potential questions and other behind-the-scenes investigatory steps likely would have explored Sussmann’s motivations and those of his clients for bringing the information to the FBI’s attention, which, in turn, the Special Counsel submits, may have influenced both whether and what type of investigation to open.

The Special Counsel also contends that Sussmann’s statement meaningfully influenced the conduct of the FBI’s investigation once it was underway. Had Sussmann revealed his attorney-client relationship with Mr. Joffe, the Special Counsel posits, “the FBI likely would have asked certain questions and conducted interviews during the investigation that would bear directly upon the information’s reliability and/or [Joffe’s] motivation in providing the information.”

The judge then noted Sussmann’s various qualms with the prosecution’s theory:

Sussmann attacks the Special Counsel’s materiality theories on several fronts. The crux of his objections is that his purported statement lacks a sufficient nexus to the initiation of the investigation, or its subsequent pursuit, to support a conclusion that it was capable of influencing the FBI’s decision-making in any meaningful way. Sussmann contends that Mr. Baker and others at the FBI were fully aware of the political nature of his client representations, which the Indictment itself notes. (Citation and parenthetical reference omitted.) And he strongly challenges the Special Counsel’s contention that the statement could have lulled the FBI into not exploring the sources and origins of the underlying information. It beggars belief, Sussmann suggests, that crack FBI investigators would not have asked such seemingly obvious follow-up questions as “who gave you this information?” or “how was the data developed?” simply because they believed he was not conveying the information on behalf of a particular client.

Though he decided to keep the case on track for trial, Judge Cooper did suggest that Sussmann’s theories are not wholly unsupported.

“[W]hile Sussmann is correct that certain statements might be so peripheral or unimportant to a relevant agency decision or function to be immaterial under § 1001 as matter of law, the Court is unable to make that determination as to this alleged statement before hearing the government’s evidence,” Cooper wrote. “Any such decision must therefore wait until trial.”

Sussmann’s trial is scheduled to begin on May 16, 2022.

The full opinion and order is embedded here:

[Editor’s note: some internal legal citations and punctuation marks have been removed from quotes in this piece so that they are easier to read. The full quotes are contained in the embedded document.]

[Image of Sussmann via YouTube screengrab.]