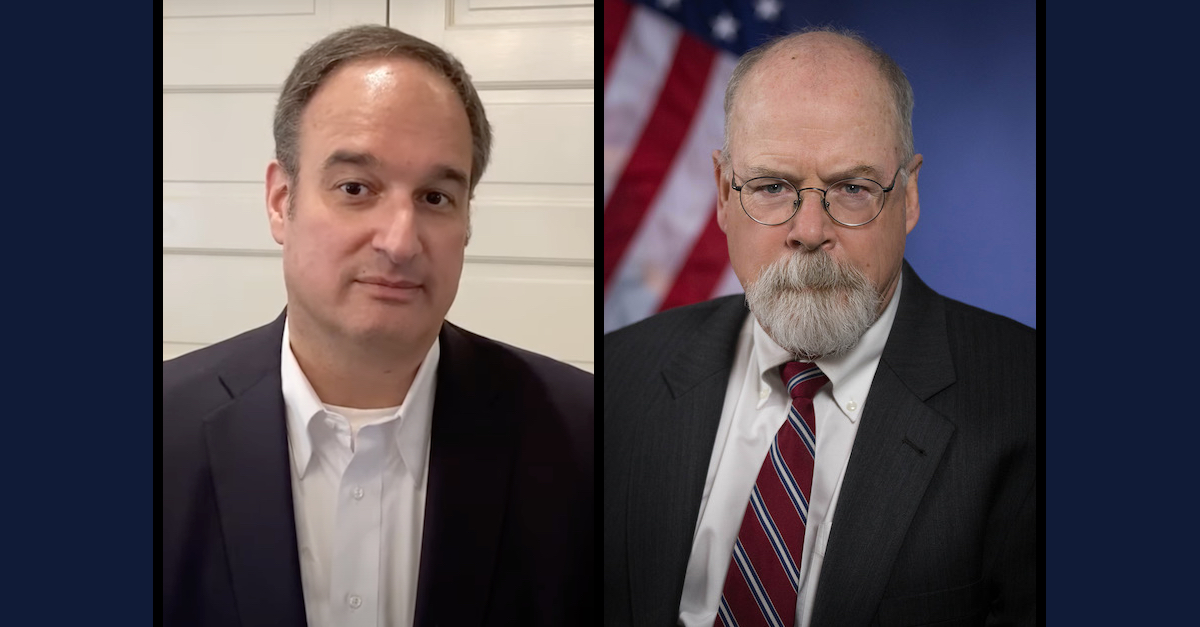

Michael Sussmann and John Durham.

Special counsel John Durham on Friday filed a 14-page opposition motion to attempts by indicted lawyer Michael A. Sussmann to have his case judicially dismissed prior to trial. In the document, Durham’s team of government lawyers argued that Sussmann’s alleged lie to the FBI was a material lie under federal law—and one which skewed the way the FBI handled the material Sussmann provided.

The Durham opposition noted that the judge “must assume the truth of the indictment’s factual allegations” for the purposes of deciding the defendant’s motion to dismiss at this stage of the proceedings.

“A pretrial motion to dismiss an indictment allows a district court to review the sufficiency of the government’s pleadings, but it is not a permissible vehicle for addressing the sufficiency of the government’s evidence,” Durham’s team wrote directly quoting case law (emphases ours, however).

Thus, the judge must look to whether the allegations on the indictment are enough to paint a rough sketch of the crime alleged — here, that’s lying to a federal officer.

As Law&Crime has previously detailed, Durham last September secured a single-count indictment against Sussmann, a high-profile Perkins Coie cybersecurity lawyer who previously worked for both the Hillary Clinton campaign and for the Democratic Party. The indictment accuses Sussmann of allegedly “mak[ing] a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement or representation” before an Executive Branch agency, namely, the General Counsel of the FBI (who at the time was James Baker). Durham claims Sussmann falsely told the FBI that the Trump Organization had a “secret communications channel” with Alfa Bank. The crime alleged is a purported violation of 18 U.S.C. §1001(a)(2). Sussmann has pleaded not guilty to the charge.

The majority of the argument centers around whether Sussmann’s alleged statements were, indeed, materially false.

In previous motions, Sussmann argued, in essence, that (1) he didn’t lie, and (2) if he did, then what he said wasn’t material to the underlying matter he asked the FBI to address. Court papers shield the name of Perkins Coie as “Law Firm-1” and Alfa Bank as “Russian Bank-1.” That matter — as the Durham opposition motion naturally and copiously recapped — was as follows:

As set forth in the Indictment, on September 19, 2016 – less than two months before the 2016 U.S. Presidential election – the defendant, a lawyer at a large international law firm (“Law Firm-1”) that was then serving as counsel to the Clinton Campaign, met with the FBI General Counsel at FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. The defendant provided the FBI General Counsel with purported data and “white papers” that allegedly demonstrated a covert communications channel between the Trump Organization and a Russia-based bank (“Russian Bank-1”). The Indictment alleges that the defendant lied in that meeting, falsely stating to the General Counsel that he was not providing the allegations to the FBI on behalf of any client. In fact, the defendant had assembled and conveyed the allegations to the FBI on behalf of at least two specific clients, including (i) a technology executive (“Tech Executive-1”) at a U.S.-based Internet company (“Internet Company-1”), and (ii) the Clinton Campaign.

The defendant’s billing records reflect that the defendant repeatedly billed the Clinton Campaign for his work on the Russian Bank-1 allegations. In compiling and disseminating these allegations, the defendant and Tech Executive-1 also had met and communicated with another law partner at Law Firm-1 who was then serving as General Counsel to the Clinton Campaign (“Campaign Lawyer-1”).

[ . . . ]

Tech Executive-1 tasked these researchers to mine Internet data to establish “an inference” and “narrative” tying then-candidate Trump to Russia.

What followed were pages of arguments about that key word — material.

Durham’s team reframed the Sussmann argument this way before attempting to rubbish it:

Distilled to its core, the defendant’s argument is as follows: At the time of the defendant’s alleged false statement, the only “discrete decision” to be made by the FBI was whether to initiate an investigation based on the information provided by the defendant. The defendant further claims that because his alleged false statement dealt only with his “purported motivation” for bringing the information to the FBI – as opposed to the substance of the information – the false statement could not have influenced the FBI’s decision whether to initiate an investigation. Defendant appears to argue that materiality should only be viewed through the lens of a specific agency decision at a discrete moment in time; in this case, whether the defendant’s information was material to the FBI’s decision to initiate an investigation.

“[C]ourts have not construed the materiality element so narrowly,” Durham’s team said. “To the contrary, a false statement is material if it has ‘a natural tendency to influence or is capable of influencing, either a discrete decision or any other function of the agency to which it was addressed.'”

The government continued:

Accordingly, the materiality of a defendant’s false statement survives long past the initiation of an investigation and encompasses the means and methods of an investigation. As discussed more fully below, and as set forth in the Indictment, the defendant’s false statement was capable of influencing both the FBI’s decision to initiate an investigation and its subsequent conduct of that investigation.

Durham’s team then said Sussmann’s arguments were “premature.” Citing a 1995 U.S. Supreme Court case, the team said the issue of materiality was an “essential element” of the crime charged and “must be resolved by a jury.” The team also said that Sussmann’s attempt to rubbish the case against him mostly relied on cases that “involved post-conviction appeals or motions to vacate the conviction after the Government presented its case at trial.” In other words, argued Durham, “none of [the Defendant’s proffered] cases support the defendant’s requested relief” — specifically “that the court dismiss the Indictment before trial because it fails to sufficiently allege that the defendant’s false statement is material.” Rather, “[w]hat the cases do show is that courts have routinely declined to usurp the jury’s role in making the determination on whether a false statement is material,” Durham’s team wrote to the judge.

After arguing to dispatch with Sussmann’s legal arguments, Durham’s lawyers cut to the heart of the matter: what the FBI would have done had Sussmann allegedly told the full truth. The crux of that part of the motion is contained in the following paragraph:

The defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel was plainly material because it misled the General Counsel about, among other things, the critical fact that the defendant was disseminating highly explosive allegations about a then-Presidential candidate on behalf of two specific clients, one of which was the opposing Presidential campaign. The defendant’s efforts to mislead the FBI in this manner during the height of a Presidential election season plainly could have influenced the FBI’s decision-making in any number of ways.

Durham’s team then went on to explain what the FBI may have done had Sussmann allegedly disclosed for whom he was working:

For example, the Government expects that evidence at trial will prove that the FBI could have taken any number of steps prior to opening what it terms a “full investigation,” including, but not limited to, conducting an “assessment,” opening a “preliminary investigation,” delaying a decision until after the election, or declining to investigate the matter altogether. Indeed, a host of factors play into the FBI’s decision of whether and how to initiate an investigation, which include, among others, the source and origins of the information. Here, had the defendant truthfully informed the FBI General Counsel that he was providing the information on behalf of one or more clients, as opposed to merely acting as a “good citizen,” the FBI General Counsel and other FBI personnel might have asked a multitude of additional questions material to the case initiation process. They might have asked, for example, whether the defendant’s clients harbored any political biases or business motives that might cast doubt on the reliability of the information. And they also likely would have conducted additional, behind-the-scenes steps (database checks, case file searches, etc.) to assess the defendant’s potential motivations and those of his clients. Indeed, it is obvious that a lawyer presenting himself as a paid advocate for a client naturally raises specific concerns related to bias, motivation, and the reliability of the information being provided.

Moreover, the Department of Justice and the FBI maintain stringent guidelines on dealing with matters that bear on U.S. elections. Given the temporal proximity to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the FBI also might have taken any number of different steps in initiating, delaying, or declining the initiation of this matter had it known at the time that the defendant was providing information on behalf of the Clinton Campaign and a technology executive at a private company.

“[A] person’s motivation in providing information to the FBI can be a highly material fact in determining whether and how the FBI opens an investigation and then conducts an investigation it has opened,” Durham’s lawyers continued. “[T]he evidence will demonstrate that the defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel had the capacity to influence the lawful function of the FBI as it related to the case initiation phase.”

Moreover, from the Durham document:

[T]he Government expects that evidence at trial will establish that the FBI General Counsel was aware that the defendant represented the DNC on cybersecurity matters arising from the Russian government’s hack of its emails, not that he provided political advice or was participating in the Clinton Campaign’s opposition research efforts. Indeed, the defendant held himself out to the public as an experienced national security and cybersecurity lawyer, not an election lawyer or political consultant. Accordingly, when the defendant disclaimed any client relationships at his meeting with the FBI General Counsel, this served to lull the General Counsel into the mistaken, yet highly material belief that the defendant lacked political motivations for his work.

Durham, therefore, asked the judge overseeing the matter — U.S. District Judge Christopher R. Cooper, an Obama appointee — to keep the case alive.

Read the full opposition below: