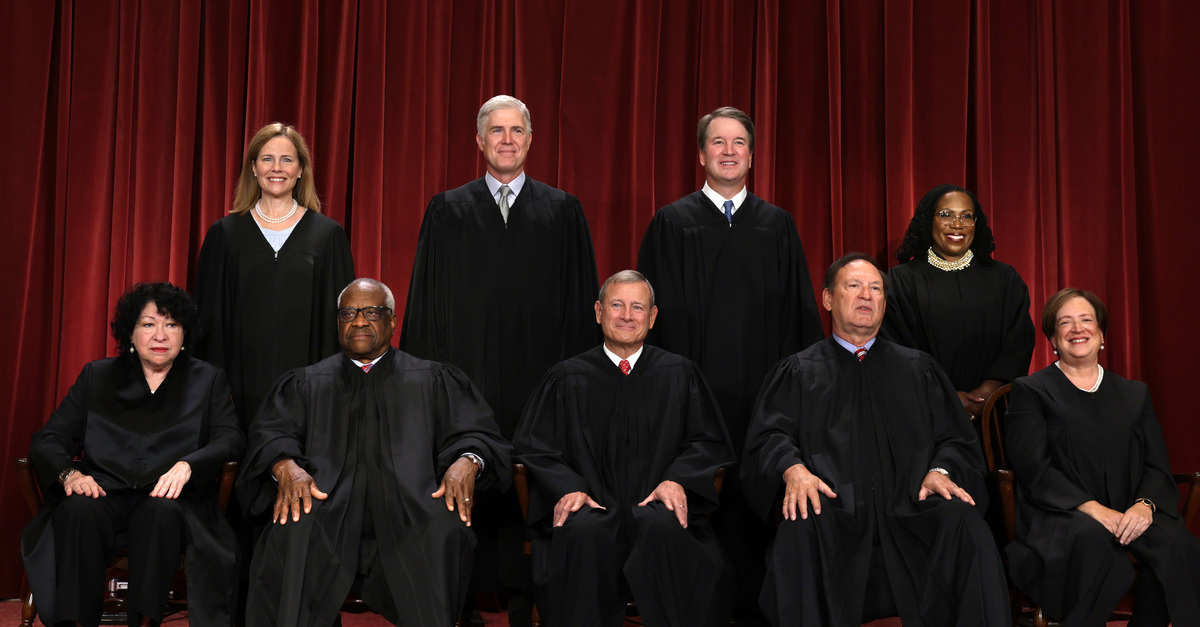

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pose for their official portrait at the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building.

The Supreme Court waded into a dispute over hardened concrete in cement trucks and “local feelings” Tuesday as they considered when an employer should be able to sue a union for damage caused by a worker strike.

The case, captioned Glacier Northwest, Inc. v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, gives the conservative Supreme Court a chance to chip away at the rights of unionized workers while simultaneously chipping away at the authority of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Glacier Northwest Inc. sells concrete to businesses in Washington. In 2017, Glacier’s truck drivers and their employer found themselves at a stalemate during contract negotiations. The drivers, who were represented by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters Local 174, went on strike by walking off the job. This was especially problematic for Glacier in that some of the trucks had been loaded with cement which would, in time, harden inside the trucks. The union says it instructed its employees to leave the cement drums spinning when they began their strike, ostensibly to minimize loss of the concrete and damage to the vehicles.

Having no drivers available to deliver the concrete, Glacier ended up having to dispose of the time-sensitive batches in order to avoid damage to 16 of their trucks. After a week of striking, the parties eventually reached an agreement.

Glacier later sued Local 174 in Washington state court and blamed the union for sabotaging its business by timing the strike purposely destroy the concrete and harm its trucks. Glacier, however, lost when the Washington Supreme Court dismissed its case on the basis that its state-law tort claim was not appropriate to bring in a labor dispute under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

Meanwhile, Local 174 filed its own complaint with the NLRB, alleging that Glacier violated federal labor law by retaliating against union members for the strike. That case is proceeding separately.

The Washington Supreme Court’s dismissal of Glacier’s state claim is the issue before the justices. Specifically, the state court found that the NLRA preempts state court lawsuits.

Glacier, on the other hand, argues that the case was properly in state court, because the Teamsters’ extreme wrongdoing fits within an exception to the preemption rule. That exception, known as the “local feeling” exception, has been used to allow state tort law to apply to cases for certain tort claims that are “so deeply rooted in local feeling and responsibility that, in the absence of compelling congressional direction, we could not infer that Congress had deprived the States of the power to act.” Glacier says that intentional destruction of an employer’s property is precisely such a matter “rooted in local feeling” as to allow the application of state tort law.

Glacier also raises a separate argument grounded in constitutional law: that a dismissal of its lawsuit would amount to a Fifth Amendment “taking”of its property without compensation.

The union warns that this case could unwisely expand the definition of “unprotected conduct” during a strike, thereby exposing workers to lawsuits that should have been blocked by federal law.

The Biden administration filed an unusual brief “in support of neither party,” which has some potential to help Glacier, though it does not align exactly with Glacier’s argument.

The government says that the Washington Supreme Court should not have dismissed Glacier’s claim when it did, because at that early phase of litigation, the court should have viewed the facts alleged in the light most favorable to the plaintiff. The remedy, therefore, would be a remand to state court. However, the administration also says that now — after the NLRB has concluded its own investigation — the state court should use the findings of that investigation when making its decision about whether the case is permitted to proceed.

The justices focused the majority of their questions on how the drivers’ actions during the strike lined up with applicable precedent. Throughout the course of the 90-minute arguments, the justices traded analogies (largely plucked from past cases) with the attorneys in an attempt to place the result of the Teamsters’ strike precisely along the spectrum of possible wrongdoing.

Former Solicitor General Noel Francisco argued on behalf of Glacier and urged the justices to adopt a ruling that treated the Teamsters’ strike as “more than a mere stoppage of work.” Francisco likened the drivers’ leaving cement in the trucks to a riverboat operator’s abandoning passengers on the water.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor took the lead from the bench during arguments and characteristically focused on the plight of the employee and pressed Francisco on how limitations on striking could be interpreted.

“Could the state tell the union not to go on strike until the end of the day?” the justice asked. When Fransisco answered that it could not, Sotomayor next asked, “then what’s the difference between that and telling workers not to strike while the truck has cement in it?”

Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson joined in as well, each asking questions to tease out whether the ruined concrete was the result of a deliberate destruction of property, or simply a natural consequence of striking.

Assistant to the Solicitor General Vivek Suri argued on behalf of the Biden Department of Justice and urged the justices to adopt a clear rule in its opinion.

A moment of levity came when Sotomayor prompted Suri, “tell me how to write this decision.”

“I suggest copying our brief, your honor” the government’s lawyer answered jokingly, to the hearty laughter of the justices.

Suri went on to suggest an opening paragraph to the Court’s ultimate ruling:

The NLRA protects the right to strike, but workers have a corresponding responsibility to take reasonable precautions to protect employers’ property. In this case, taking the allegations true, such precautions were not taken, therefore the conduct was not even arguably protected and the Washington Supreme Court’s decision is reversed.

Attorney Darin Dalmat argued on behalf of the Teamsters that Glacier essentially sued over nothing more than “a work stoppage” — a retaliatory action that lies at the heart of what the NLRA was meant to prohibit. Dalmat reminded the justices that the Supreme Court has never found that workers forfeited their legal rights “simply because perishables spoiled,” and said the cement loss should not be viewed as “intentional destruction” of Glacier’s property.

Jackson pushed Dalmat to clarify the limits of his argument.

She asked whether he agreed that “when a union deliberately orchestrates a scheme for the very purpose of destroying the employer’s property, there is no plausible argument” that their actions would be legally protected. Dalmat answered that even such deliberate behavior would not constitute an outer limit, because the phrase “employer’s property” could be construed in a manner so broad as to be problematic.

Throughout the lengthy oral arguments, Justices Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh were noticeably silent, and comments from Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas were minimal.

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.

[image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]