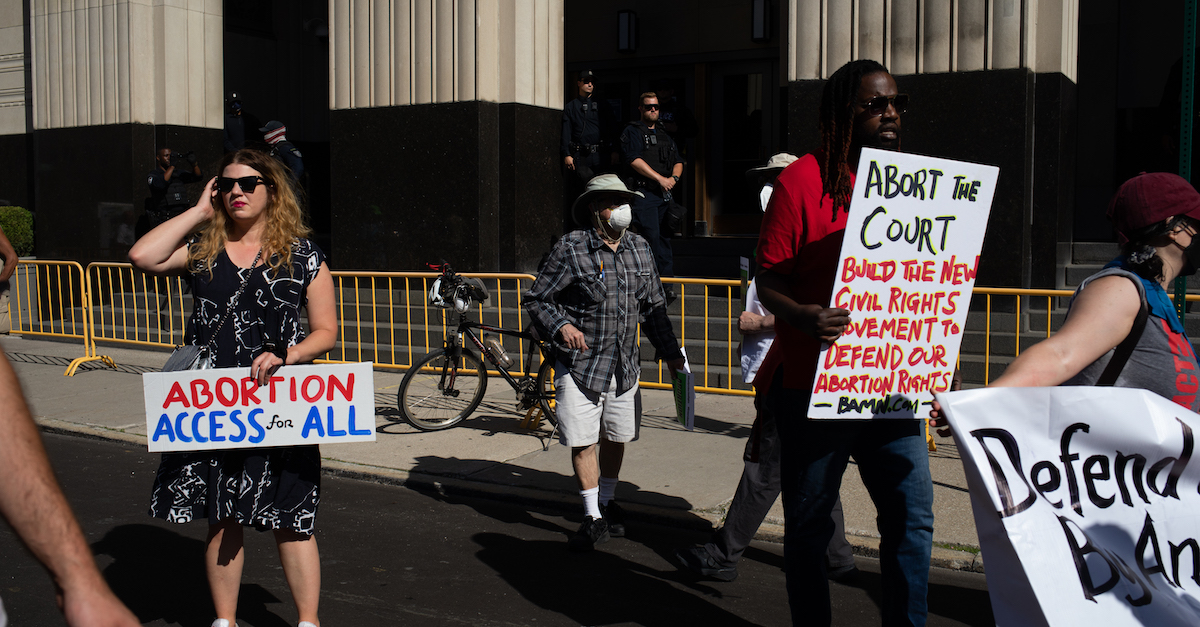

Abortion rights demonstrators gather to protest the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health case on June 24, 2022 in Detroit, Michigan.

While many concerned about reproductive rights are warning about the possible spread of fetal parenthood laws in states which oppose abortions, civil lawsuits brought on behalf of the estate of an aborted fetus — which do not require any new legislation, and can be brought even in states where abortion is legal, or where prosecutors refuse to enforce laws criminalizing abortions — are already beginning to have an impact, and suits brought on behalf of a living fetus could go even further.

That’s why it’s important for everyone concerned about reproductive rights to understand these various concepts, and how they can be used to limit reproductive rights.

Fetal Personhood

Fetal personhood laws — which regulate pregnancy and those involved much more broadly than anti-abortion laws — are “the next battleground in the fight over abortion rights in the US,” according to The Washington Post, since they grant a fetus the same legal rights (including to life) as a person.

The Boston Globe warns that they could “upend the meaning of equality under the law,” and deny states “the authority to allow abortions in cases of rape or incest.”

The New York Times adds:

Fetal personhood, which confers legal rights from conception, is an effort to push beyond abortion bans and classify the procedure as murder. . . . anti-abortion activists are pushing for a long-held and more absolute goal: laws that grant fetuses the same legal rights and protections as any person. So-called fetal personhood laws would make abortion murder, ruling out all or most of the exceptions for abortion allowed in states that already ban it. . . . They have the potential to criminalize common health care procedures and limit the rights of a pregnant woman in making health care decisions. The U.S. Supreme Court decision returning the regulation of abortion to the states has opened new interest in the laws, and a new legal path for them.

Some medical groups have opposed such laws, arguing that they would would also criminalize IUDs and other methods of contraception, and affect in vitro fertilization (IVF). They warn that disposing of unused fertilized eggs, or selectively eliminating implanted eggs (as is common), could result in murder charges.

Georgia already has a law (House Bill 481) which grants personhood (the rights of human beings) after around six weeks of pregnancy. Five other states have already passed fetal personhood laws, but three were struck down or are now enjoined by courts.

Georgia’s law is entitled the “The Living Infants Fairness and Equality Act,” and it defines an “unborn child” as “a member of the species Homo sapiens at any stage of development who is carried in the womb.” It also provides that the “unborn” are entitled to full protection under the 14th Amendment.

Alabama’s voters adopted a constitutional amendment which protects fetal rights. Under it, women who use certain drugs during pregnancy can face up to 99 years in prison, and at least 20 women have faced the harshest possible criminal charges when they used drugs and then suffered pregnancy loss.

For nearly 20 years, Texas has also afforded fetuses legal rights when it comes to criminal cases. The Texas Penal Code was updated in 2003 to identify an “unborn child at every state of gestation from fertilization until birth” as “an individual” for cases of murder and assault.

That law has been upheld by Texas’ highest criminal court of appeals, allowing the state to prosecute individuals who cause the “death of or injury to an unborn child.” Under it, a man was recently imprisoned for life without parole after being found guilty of capital murder after a jury found the man guilty of causing the death of his ex-wife’s 5-week-old fetus.

In short, fetal personhood laws, which are being pushed in several states and even at the federal level, support and go even further than laws which simply criminalize abortions as well as those who perform them or assist in any way.

However, as a practical matter they appear to be limited to states which already have laws which ban abortions. Also, to be effective, there must be district attorneys or others who prosecute criminals willing to actually bring criminal charges; something many prosecutors may well be reluctant to do, and which several have already said they will refuse to do.

But that’s where fetal estate lawsuits come in, since they do not necessarily require any new legislation; can be effective in preventing abortions even in states where it has not been made a crime; and do not depend upon prosecutors or other state officials to take any action.

Fetal Estate Lawsuits

Thus fetal personhood laws may not even be strictly necessary for those opposing abortions, since some courts have been willing to recognize and permit civil lawsuits — which do not require any action by a prosecutor — on behalf of or to vindicate the rights of fetuses through their estates, stillborn “children,” and even — in one remarkable case — by the victim of a tort as a pre-zygote, and against doctors, fathers, and others.

Moreover, a petition now before the U.S. Supreme Court seeks a ruling that fetuses have legal standing to file lawsuits in a new filing which could provide such groups and also individuals with a new legal weapon against abortions, abortion providers, and perhaps even against women seeking abortions.

The petitioners argue, in effect, that an earlier ruling in Rhode Island, denying unborn children the legal right to sue on their own behalf, should be vacated in light of the Court’s recent decision overruling Roe v. Wade, the case which had established a constitutional right to an abortion in many situations.

While comments and speculation on this new legal-standing development have tended to focus on what it may mean in the future, the legal theory that “pre-born children” may have rights has been accepted by some courts for more than 30 years, and has already proven to be a useful weapon for those opposed to abortions, including fathers (married or not) whose unborn children were “killed” against their wishes.

Here are just a few examples:

1. In 1985, in Amadio v. Levin, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania held that a child which was stillborn as a result of prenatal injuries could sue the mother’s obstetricians on his own behalf; in effect recognizing that a fetus enjoyed a separate legal existence independent of the mother, and could therefore sustain — and sue for — his own injuries.

2. In 1987, in Didonato v. Wortman, the North Carolina Supreme Court held that the word “person” in the state’s civil Wrongful Death Act includes a fetus, so that a valid legal action could be brought against the doctors allegedly responsible for the injuries to a viable but unborn child.

3. Then, in 1993, in Coveleski v. Bubnis, the court announced that “we joined the majority of jurisdictions which recognized a cause of action for a fully developed stillborn. In so doing, we rejected our previous line of cases that limited the right to bring a cause of action to those children born alive. We found that it was illogical to permit a cause of action to be maintained on behalf of a child that survived only an instant, while denying the same right to a fully developed fetus which, prior to its demise, was capable of an independent existence.”

4. And in an earlier (1964) and quite remarkable case of Zepeda v. Zepeda, an adult was permitted to sue his father for a tort allegedly committed upon him at about (and perhaps even before) the moment of his own conception.

As the Zepeda court explained:

The case at bar seems to be the natural result of the present course of the law permitting actions for physical injury ever closer to the moment of conception. . . . we have seen that it is not too important whether the plaintiff’s life began during or subsequent to the act of procreation. There is no certainty as to the exact moment conception takes place. It occurs when the male semen contacts and fertilizes the female ovum and this may happen at the time of coition or within a few hours thereafter. If the plaintiff was conceived before the completion of the act he became a living, human organism concurrently with the wrongful act. If his conception took place after the act, he was a potential being with essential reality at the time of the act. The seed was planted, the life process was started, life ensued and birth followed. The defendant’s wrongful act simultaneously procreated the being whom it injured.

More recently there has emerged a variant, a new weapon in the arsenal of those who oppose abortions; a lawsuit, on behalf of the “estate” of the aborted fetus, against those who played any role in aborting it.

This is a tactic which has been used at least twice recently, and was just upheld by a judge.

In Arizona, Mario Villegas was allowed to establish a legal estate for the fetus, dubbed “Baby Villegas,” in order to sue doctors who had provided abortion pills to his then wife some four years earlier.

The Arizona action was based upon an earlier lawsuit by an Alabama man, Ryan Magers, who hadn’t wanted his ex-girlfriend to have an abortion. He persuaded a probate judge to appoint him as a representative of the estate of the aborted fetus so that he could then file a wrongful death lawsuit against those involved.

Although the Alabama lawsuit was eventually dismissed, it — like other similar lawsuits — can cause very serious consequences for those who have been sued, including the stress and expense of being forced to defend themselves. For example, the doctor sued for prescribing abortion pills in Arizona had her annual medical malpractice insurance rate more than doubled from $32,000 to $67,000.

Those who support the availability of abortions should be especially concerned because all of the above occurred at a time when a woman’s right to an abortion — i.e. to destroy a fetus — was constitutionally protected.

Now that Roe has been overruled by the Supreme Court, the opportunities for this tactic to be used as a powerful weapon against abortions — especially in jurisdictions where prosecutors may decline for many reasons to bring criminal charges, so that private civil lawsuits may be the only effective weapon — have exploded.

Indeed, it now appears that this new Supreme Court filing, if acted upon favorably by the Court, could provide strong support as well as publicity for this legal tactic. Others agree.

For example, law professor Lucinda Finley says such lawsuits are a “harbinger of things to come,” and that she expects anti-abortion activists, together with state legislators, to use “unprecedented strategies” to slash the number of abortions.

Another advocate for reproductive rights says the Arizona lawsuit is part of a larger agenda; “It’s a lawsuit that appears to be a trial balloon to see how far the attorney and the plaintiff can push the limits of the law, the limits of reason, the limits of science and medicine.”

Lawsuits by a Living Fetus

If even a few judges in some states agree that an aborted (and therefore no longer living) fetus can have a legal estate which is represented by its biological father or by some other person, this seems to imply that living fetuses, before being destroyed, have some legal rights which can be protected by judges in civil proceedings.

These might include court orders, perhaps obtained by husbands or other biological fathers, prohibiting or at least limiting pregnant women from using illegal drugs, smoking tobacco and/or marijuana, drinking or at least drinking to excess, and even engaging in various jobs (e.g., as a police officer or fire fighter) or activities (e.g., horseback riding) which might unreasonably endanger a fetus.

Indeed, even years earlier when there still existed a constitutional right to an abortion, women were prosecuted for endangering the fetus by engaging in risky activities while pregnant — such as using crack (and then giving birth to “crack babies”), abusing alcohol, or even smoking cigarettes.

In such situations, they sometimes tried to argue that there was no legal wrong in engaging in such activities because they had a constitutional right to abort (kill) their fetus.

But, it was argued in rebuttal, they had a right under Roe v. Wade to kill the fetus only to spare themselves the physical, mental, and other injuries and/or burdens which would be caused by being forced to actually give birth. Having decided to give birth, they no longer had any right under Roe to kill the fetus, or even to cause it injury.

Lawsuits based upon the fetus-estate or other theories, even if eventually dismissed or otherwise unsuccessful, can nevertheless have devastating impacts on anyone involved in helping — or even simply counseling — a pregnant women to have an abortion (“kill the fetus”); either a procedure performed by a surgeon or, as in the Arizona case, even one which resulted from a prescription for pills.

Thus it is quite likely that the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision has opened the floodgates to a large number of legal actions based upon new, novel, and unprecedented and untested legal theories, even in the absence of any new statutes.

Unless and until the law regarding fetuses, and the potential or possible legal rights of fetuses and their estates becomes settled — something likely to take many years, and to involve different results in various states — legal uncertainty and the risk of exposure to novel legal actions is likely to make doctors, hospitals and other health care centers, insurance companies, private employers, and even friends and family members, to be reluctant to become involved, directly or even indirectly, with abortions.

Professor Banzhaf, of the George Washington University Law School, is known for creating and writing about new and novel legal theories, and for using them against major social problems. He has been called by the media: “The Man Behind the Ban on Cigarette Commercials,” “a Driving Force Behind the Lawsuits That Have Cost Tobacco Companies Billions of Dollars,” an “Entrepreneur of Litigation, [and] a Trial Lawyer’s Trial Lawyer,” a “King of Class Action Law Suits,” and “The Law Professor Who Masterminded Litigation Against the Tobacco Industry,” Banzhaf does not advocate in favor of or against any of the lawsuits or legal theories discussed in this piece.

[Image via Emily Elconin/Getty Images]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.