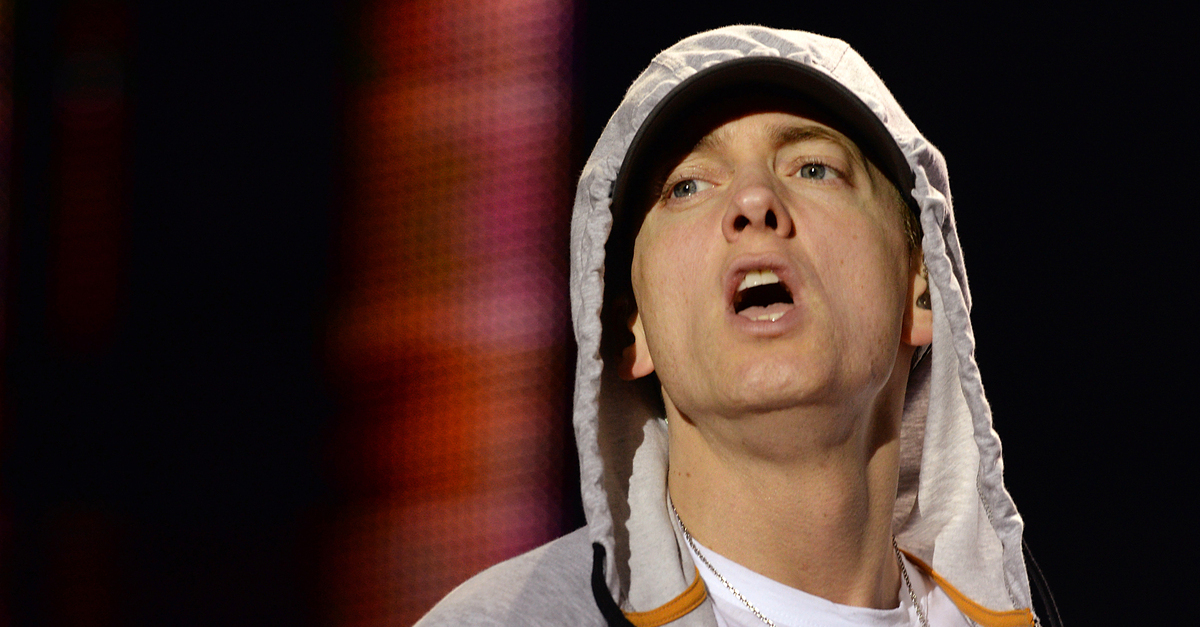

US rapper Eminem performs on August 22, 2013 during a concert at the Stade de France in Saints-Denis, near Paris.

The music publishing company that owns music penned by multiplatinum recording artist Marshall Mathers, who performs under the stage name Eminem, won a recent legal skirmish against Spotify and the music streaming service’s CEO and Swedish billionaire Daniel Ek.

The latter will now have to provide sworn testimony in a long-running copyright infringement lawsuit brought by Eight Mile Style LLC against Spotify over the service allegedly offering users 243 Eminem songs on demand without first obtaining the proper licenses.

The songs in question make up the majority of the rapper’s repertoire, which currently stands at a little under 400 compositions.

Eminem himself, however, does not own the rights to those songs, is not consulted on the publishing company’s decisions, and is not involved in the litigation.

“Eight Mile Style is not owned or controlled by Eminem,” the hip-hop artist’s spokesperson Dennis Dennehy told Law&Crime. “It’s a production company owned by Joel Martin and The Bass Brothers that controls the publishing rights to his early catalog. He is not involved in this lawsuit in any way.”

In sum, the publishing company alleges that those 243 older songs have been streamed billions of times and, lacking the proper licensing, have resulted in upwards of $36.45 million in lost revenue.

“On information and belief, despite their not being licensed, the recordings of the Eight Mile Compositions have streamed on Spotify billions of times,” the complaint filed in August 2019 says. “Spotify has not accounted to Eight Mile or paid Eight Mile for these streams but instead remitted random payments of some sort, which only purport to account for a fraction of those streams.”

The lawsuit takes aim at Spotify’s business model and mentions prior occasions in which the streamer has been sued for infringement and forced to account for that behavior [emphasis in original]:

Spotify has built a multi-billion dollar business (its current market cap at approximately $26 billion) with no assets other than the recordings of songs by songwriters like Eminem made available to stream on demand to consumers on its digital platform. Yet, as the Lowery and Ferrick class action lawsuits and the settlement with the National Music Publishers’ Association (“NMPA”) have firmly established, Spotify built its behemoth by willfully infringing on the copyrights of creators of music worldwide without building the infrastructure needed to ensure that songs appearing on the Spotify service were properly licensed or that appropriate royalties were paid on time (or at all) in compliance with the United States Copyright Act. Spotify’s apparent business model from the outset was to commit willful copyright infringement first, ask questions later, and try to settle on the cheap when inevitably sued. It later included working (with their equity holders, such as the major music publishers) to pass legislation that would purport to get them off the hook scot-free.

Spotify, in turn, countersued Kobalt Music Publishing in May 2020, bringing them into the lawsuit as a third party on the duel basis that: (1) Eight Mile Style’s underlying claims lacked merit but; (2) that if there was any merit to the claims, Kobalt should bear the burden of any infringement because they, Kobalt, led Spotify to believe they were allowed to license the songs in question on Eminem’s behalf.

“For years, Kobalt granted licenses to Spotify for musical compositions allegedly owned by Eight Mile,” the third-party complaint alleges. “Kobalt had the express or apparent authority of Eight Mile to do so on Eight Mile’s behalf, and certainly (at the very least) led Spotify to believe that it had such authority.”

“If Spotify were deemed liable to Eight Mile, the responsibility for such liability rests with Kobalt because, through its contractual representations and course of conduct, Kobalt caused Spotify to believe that Kobalt had granted valid licenses to the Compositions, and Spotify made sound recordings available on its service on the basis of that reasonable belief,” the streamer’s argument goes on. “Kobalt agreed to indemnify Spotify for precisely this type of claim.”

Procedural wrangling continued on for some time as Eight Mile Style later moved to include the Harry Fox Agency, a storied music rights and licensing management company, into the lawsuit as well.

Things picked up in March of this year when Magistrate Judge Chip Frensley okayed Eight Mile Style’s request to depose Ek – shrugging off the streamer’s major argument that their CEO has a lot of work to do.

That earlier order noted:

The Court is inclined to agree with Plaintiffs that “Mr. Ek’s entire argument for burden is, essentially, that he is busy.” … Undoubtedly Mr. Ek has a full schedule at the present time as well; the Court credits Spotify’s assertion that he is very busy indeed. Yet, the issue of proper licensing relationships with the artists whose work comprises the entirety of Spotify’s business and its sole product is surely also a matter of importance to Spotify, worthy of some of Mr. Ek’s time and attention.

In recognition of the fact that Mr. Ek has denied having personal knowledge of many areas of potential inquiry, and to minimize the likely annoyance to Mr. Ek and the disruption of his schedule, Plaintiffs may take the deposition of Mr. Ek by remote means only for a maximum of three hours.

Spotify responded by saying the magistrate’s order violated a prior discovery order and that even if he is deposed, Ek shouldn’t have to testify under oath until the damages phase – if the lawsuit gets that far. The streamer asked the district judge to overturn her magistrate’s earlier ruling.

On July 15, 2022, U.S. District Judge Aleta A. Trauger declined Spotify’s request.

“The court has little difficulty rejecting Spotify’s argument,” the judge noted – citing a relevant federal rule of civil procedure. “Spotify suggests that the Magistrate Judge committed an error of law under that rule by failing to properly consider the possibility that another witness, former Spotify executive and in-house counsel James Duffett-Smith, would be a less burdensome alternative witness. The Magistrate Judge, however, engaged in a factual inquiry into whether Duffett-Smith was an adequate alternative to Ek and concluded that he was not because (1) Duffett-Smith, who is an attorney, would be more constrained by privilege and (2) the evidence had not established that Duffett-Smith’s knowledge was identical to Ek’s.”

Trauger went on to note that Spotify’s major error in seeking to keep Ek under wraps was arguing that the magistrate’s order was an error of law – and therefore subject to a very high standard for reversal But the judge went on to say that agreed with the factual basis and legal analysis the magistrate’s order was based on anyway.

“When a court considers the burdens associated with deposing an objected-to witness, the court must, of course, consider all of the considerations unique to that potential deponent, including those related to his unique job title and responsibilities, if applicable,” Trauger explained. “The Magistrate Judge, however, acknowledged those very considerations and engaged in a factual inquiry regarding both the amount of hardship involved in deposing Ek and the potential availability of information from other sources, and the Magistrate Judge concluded that an appropriate balance could be reached by allowing a time-limited, remote deposition of Ek that could be completed from virtually anywhere on Earth in less than half a day.”

The court’s full order is available below:

[Image via PIERRE ANDRIEU/AFP via Getty Images]

Editor’s note: this story has been amended post-publication to clarify that Eminem does not own the publishing company at the heart of the litigation and is not involved in the lawsuit.