ABA Legal Fact Check debuted in August 2017 and is the first fact check website focusing exclusively on legal matters. This article has been republished with permission.

On Feb. 15, President Donald Trump signed a declaration of emergency to fund construction of a border wall, after ending the threat of another partial government shutdown but triggering another battle that likely will be headed to the federal courts.

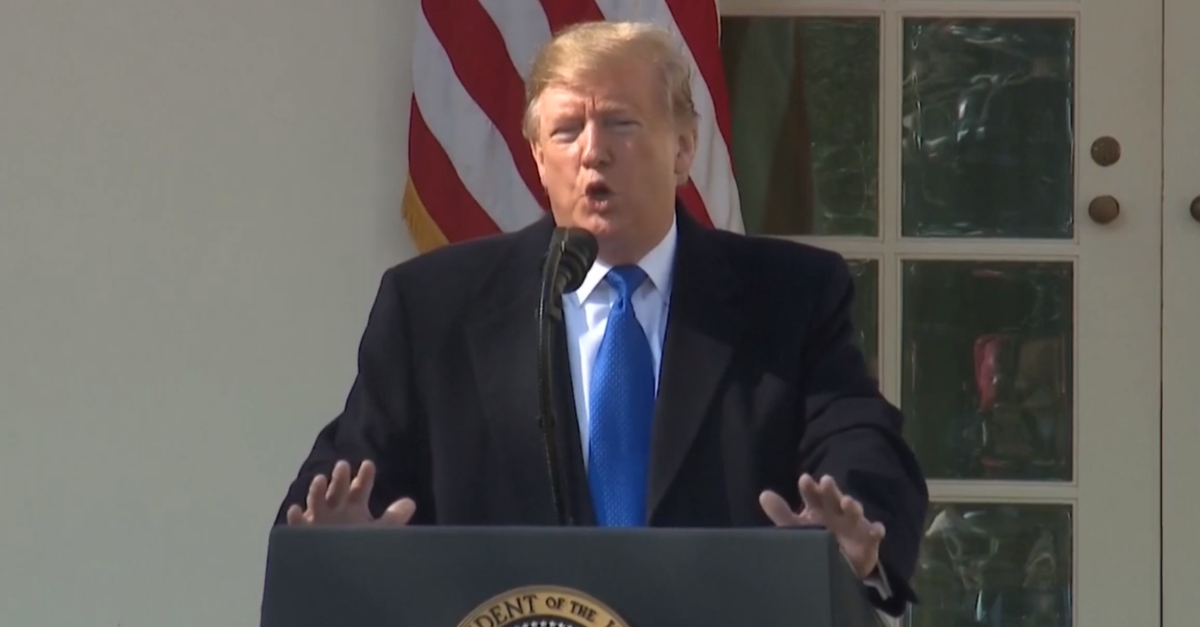

“I expect to be sued,” President Trump said on Feb. 15. “I think we will be very successful in court. … Sadly, we will go through a process, and happily we will win.” Based on case and statutory law, what are the president’s chances of prevailing with the wall?

The budget deal the White House made with Congress, which the president signed, includes $1.375 billion for 55 miles of new fencing along the border, funding that falls short of the $5.7 billion the president sought for 234 miles of steel walls. But shortly later, the president said he would redirect additional money from other sources to have as much as $8 billion for border security — enough to complete the wall.

Issuing a presidential declaration for a state of emergency is not unprecedented. The National Emergencies Act, enacted in 1976, permits a president to declare a national emergency by providing a specific reason for it. That would allow use of emergency powers under other laws, permitting the White House to declare, in theory, martial law, suspension of civil liberties, expanding the military, seizing property and restricting trade, communications and financial transactions.

Every recent president has used the emergencies act, and more than two dozen states of emergency are currently active — and have been renewed annually.

The reasons for invoking states of emergency vary, and often are employed to restrict the trade or financial freedom of countries, like Iran, and their residents to do business in the U.S. But the powers can range widely. In recent years for instance, President George W. Bush invoked emergency powers after the 9/11 attacks; in 2009 President Barack Obama declared an emergency giving authorities and hospitals extra powers to combat the H1N1 flu virus.

However, the law limits what a president can do under a state of emergency, as a 2007 Congressional Research Service report points out.

Except for the habeas corpus clause, the U.S. Constitution makes no allowance for the suspension of any of its provisions during a national emergency. And either the judiciary or Congress can restrain a president’s emergency powers.

The 1976 act specifically states that “any national emergency declared by the president … shall terminate if (1) there is enacted into law a joint resolution terminating the emergency; or (2) the president issues a proclamation terminating the emergency.” It also commands Congress to review it periodically “not later than six months after a national emergency is declared.”

In 1983, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that for a congressional action to take legal effect, the action must be presented to the president for signature or veto. If the president opts to take the latter action, both chambers would need a two-thirds vote to block it.

The courts have also determined that states of emergency are judicially reviewable.

During the Korean War in 1952, for example, in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, the U.S. Supreme Court by a 6-3 vote blocked President Harry Truman’s attempt to nationalize the steel industry during a labor dispute.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Robert Jackson put forth a three-part test related to the overreach of presidential power relied upon by courts today. Jackson said the president’s powers were at their height when he had direct or implied authorization from Congress to act; at their middle ground or “a zone of twilight” when acting without either a congressional grant or denial of authority; and “at its lowest ebb” when a president acts against the expressed wishes of Congress.

The Constitution gives Congress the power of the purse. So, the central question centers on whether the president can legally re-direct appropriated funds to finish the border wall under an emergency declaration. Congressional efforts to block the president could be difficult because of the possibility of a presidential veto. More likely, the matter will be decided following a court challenge.

Read more of ABA’s Legal Fact Check series here.

[Screengrab via The Washington Post]