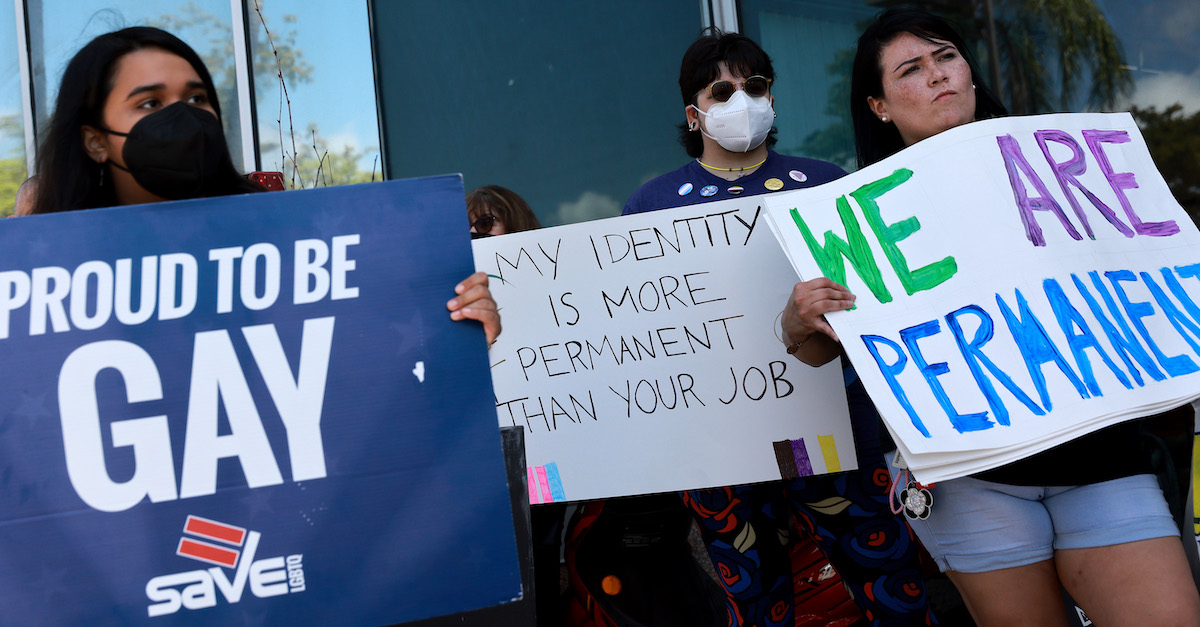

Opponents of the Florida ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill protest in March 2022.

An en banc panel of federal appeals court judges has refused to reconsider a decision by a smaller three-judge panel to allow so-called “conversion therapy” in some Florida municipalities to continue unabated while a case which challenges a prohibition on the practice winds its way through the courts.

The full U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit ruled Wednesday to deny rehearing in a case about the municipalities’ bans on “conversion therapy,” a controversial practice aimed at discouraging the sexual and gender expression of LGBTQ+ youth. The court’s ruling means its November 2020 preliminary injunction stands, and the regulations cannot be enforced while the underlying case proceeds.

A three-judge panel on the 11th Circuit ruled in November 2020 that the laws which prohibit conversion therapy violate the First Amendment because the laws are content-based restrictions against speech.

The decision marks another win for efforts by conservatives, but critics say the laws marginalize those who identify as LGBTQ+ in the Sunshine State.

Earlier this year, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill prohibiting “classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity” through third grade. That bill is often referred to by its opponents as the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

At issue before the 11th Circuit were local ordinances adopted by Palm Beach County and the City of Boca Raton, both of which prohibited sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE), which are defined as “any counseling, practice or treatment performed with the goal of changing an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity, including, but not limited to, efforts to change behaviors, gender identity, or gender expression, or to eliminate or reduce sexual or romantic attractions or feelings toward individuals of the same gender or sex.”

The ordinances also contained a specific carve-out for “counseling that provides support and assistance to a person undergoing gender transition.”

Two licensed therapists, Robert Otto and Julie Hamilton, said while they have no ability to change a person’s sexual orientation, they use “talk therapy” to “reduce same-sex behavior and attraction” and to eliminate “confusion over gender identity.” Hamilton and Otto filed a federal lawsuit to challenge the ordinances. The municipalities maintained that even if the SOCE provided by plaintiffs consists entirely of speech, it poses serious health risks to children and adolescents, including increased risk of depression and suicide.

The court’s ruling means that the ordinances — the bans on SOCE — will themselves be blocked while the case proceeds through litigation toward a final determination of their legality.

2020 Ruling: Local Laws Banning “Conversion Therapy” Are “Content-Based Regulations.”

After the district court refused to block enforcement of the laws, a three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit reversed. The panel included U.S. Circuit Judges Britt Grant and Barbara Lagoa (both Donald Trump appointees) voting to block the regulations, and Beverly Martin (a Barack Obama appointee) in dissent.

Judge Grant wrote that 14-page opinion for the majority in 2020. Grant and Lagoa found that because the ordinances involved constitute “content-based regulations,” they are subject to strict scrutiny.

“After all,” Grant wrote, “the plaintiffs’ counseling practices are grounded in a particular viewpoint about sex, gender, and sexual ethics,” and that while “[t]he defendant governments obviously hold an opposing viewpoint,” they cannot legally engage in “bias, censorship, or preference” about the therapists’ protected viewpoint. Grant criticized the district court’s ruling for putting SOCE into “a kind of twilight zone of ‘professional speech’ or ‘professional conduct,'” while it warrants no such special treatment.

The majority applied strict scrutiny to the ordinances and found no problem with the government’s compelling interest.

“It is indisputable ‘that a State’s interest in safeguarding the physical and psychological well-being of a minor is compelling,'” Grant wrote, adding: “We have no doubt that the local governments here have a strong interest in protecting children.”

The judge noted, however, that the government’s “legitimate authority to protect children . . . ‘does not include a free-floating power to restrict the ideas to which children may be exposed.'”

The court found that the problem with regulations against SOCE is that there is insufficient evidence to show that SOCE is actually harmful to children. Attitudes about homosexuality, said Grant, can change. From the opinion:

Only in 1987 was homosexuality completely delisted from the Manual. The Association’s abandoned position is, to put it mildly, broadly disfavored today. But the change itself shows why we cannot rely on professional organizations’ judgments—it would have been horribly wrong to allow the old professional consensus against homosexuality to justify a ban on counseling that affirmed it. Neutral principles work both ways, so we cannot allow a new consensus to justify restrictions on speech. Professional opinions and cultural attitudes may have changed, but the First Amendment has not.

Grant called the court’s ruling “a difficult conclusion,” and noted that “it does not mean that society is powerless to remedy harmful speech.” The judge suggested that tort and professional malpractice law can regulate “bad acts that produce actual harm.”

“People who actually hurt children can be held accountable,” said the judge, “but ‘[b]road prophylactic rules in the area of free expression are suspect.'”

In a lengthy dissent, U.S. Circuit Judge Beverly Martin acknowledged that “the rare case” survives strict scrutiny, but she still “believe[s] this is such a case.” Martin took issue with the majority’s suggestion that “people who actually hurt children can be held accountable” in other ways, or that SOCE is not clearly harmful.

Martin pointed to an American Psychological Association’s Task Force Report on the subject, which found that “patients who undergo SOCE experience negative consequences including ‘anger, anxiety, confusion, depression, grief, guilt, hopelessness, deteriorated relationships with family, loss of social support, loss of faith, poor self-image, social isolation, intimacy difficulties, intrusive imagery, suicidal ideation, self-hatred, and sexual dysfunction.'”

Further, from the dissent:

Certainly worth considering, too, is the recognition that homosexuality is not a mental illness, as well as the particular vulnerability of minors as a test-study population. All of this evidence leads to the inescapable conclusion that performing efficacy studies for SOCE on minors would be not only dangerous (by exposing children to a harmful practice known to increase the likelihood of suicide) but pointless (by studying a treatment for something that is not a mental-health issue). As the District Court recognized, legislative bodies should “not need to wait for further evidence of the negative and, in some cases, fatal consequences of SOCE before acting to protect their community’s minors.

The dissent further chastised the majority for “entirely discount[ing] ‘professional organizations’ judgments,'” when that judgment is not only “quite relevant,” but also, “backed up by a mountain of rigorous evidence.”

Conversion Therapy Takes a “Profound Human Toll.”

After the ruling from the three-judge panel, the Florida municipalities requested a rehearing by the full 11th Circuit, which a majority of the full court has now voted to deny.

U.S. Circuit Judge Grant authored a 15-page concurring opinion to highlight the panel’s tersely-worded denial. Grant was again joined by U.S. Circuit Judge Lagoa, as well as by a third Trump appointee, U.S. Circuit Judge Elizabeth Branch. Also on the panel were Chief Judge William Pryor, a George W. Bush appointee, and Trump-appointed Circuit Judges Kevin Newsom, Andrew Brasher, and Robert Luck.

Grant wrote that the “panel opinion thoroughly explains why a fair-minded and neutral application of longstanding First Amendment law dooms the ordinances” before the judge continued to attack specific points offered by the dissenting judges.

U.S. Circuit Judge Adalberto Jordan penned a 15-page dissent. It was joined by fellow Obama appointees Robin Rosenbaum and Jill Pryor and by Bill Clinton appointee Charles R. Wilson.

Jordan argued that because the case is a rehearing of a decision on a preliminary injunction (as opposed to a final decision on the merits), the full court should have been more deferential to the district court in its factual findings. For example, offered Jordan, “the district court found that the ‘practice’ or ‘perform[ance]’ of SOCE therapy is different from ‘a dialogue between patient and provider’ about that treatment.” By contrast, the panel made the mistaken determination that SOCE is a non-medical practice that consists of unregulable speech.

Jordan offered the following analogy:

No one would doubt that the government can forbid a psychiatrist from advising a patient with severe depression to take his or her own life immediately and put an end to the suffering. And that content-based prohibition, it seems to me, would be sound under the First Amendment even if there was not a controlled study showing that most depressed patients given that advice followed it and committed suicide. That is what the district court sensibly concluded here as to SOCE therapy.

The dissent argued that the majority should have conducted more fact-finding in order to render a proper decision:

Determining the nature of SOCE therapy requires answers to a number of questions. Is SOCE therapy just talk? Is SOCE therapy medical treatment rendered by licensed professionals? Is SOCE therapy a combination of the two? These are quintessential “what” or “how” questions. The inquiry, which seeks to determine what SOCE therapy is and how it is performed on the ground, is inherently factual.

Jordan also had harsh words for his colleagues:

From my perspective, what the panel majority did here—ignoring and/or revising the district court’s factual findings and failing to apply the clear error standard—is seemingly becoming habit in this circuit.

Rosenbaum also authored a separate 78-page dissent, which Pryor joined.

Rosenbaum criticized the majority for essentially dismissing talk therapy in its entirety. Rosenbaum wrote:

That’s how the panel opinion characterizes talk therapy (psychotherapy) that is practiced by a licensed mental-healthcare professional who has attended years of school and clinical training, and that is administered in a private setting for the purpose of helping a client with a mental-health condition. In the Concurrence’s view, there’s no difference between this mental-healthcare treatment and “political, social, and religious debates.”

Rosenbaum, calling the majority decision an “uninformed take on talk therapy,” argued that giving blanket First Amendment protection to such therapeutic intervention would mean that no state or local government could regulate the practice in any way. At its worst, Rosenbaum argued, that would mean a standard that prevents states from “even disciplin[ing] licensed mental-healthcare professionals who violate the standard of care in administering talk therapy—no matter how incompetent or dangerous a practitioner’s practice of psychotherapy may be.”

Rosenbaum emphasized the “human toll” that efforts to change young people’s sexual orientation can have:

That includes the practice this case is about—sexual-orientation change efforts (“SOCE”), which is associated with more than doubling suicide attempts in the many LGBTQ youths who have been subjected to it. Take a moment to think about that profound human toll—on those subjected to SOCE, those who care about them, and the world, which forever loses out on their talents and contributions.

Rosenbaum slammed the majority for its “incorrect” and “grievous” mistake in this case, writing: “There’s a better answer.”

“Contrary to the Concurrence’s mischaracterization of my dissent,” Rosenbaum noted, “it doesn’t involve targeting speech because we’re not fond of the viewpoint it expresses.”

The 11th Circuit covers federal judicial districts in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia.

[Image via Joe Raedle/Getty Images]