Monday, SCOTUS will hear oral arguments in a case meant to tell us us just which words are too scandalous for our 2019 eyes and ears. Iancu v. Brunetti stands to have broad impact on First Amendment and trademark law, and its decision will be an important example of the justices at work in a case that doesn’t exactly fall along liberal/conservative lines. Trademark laws are intended to protect the integrity of the marketplace and staunch unfair business practices; they now collide with censorship, claims of misogyny, and profanity — making the case ripe for some good, old-fashioned legal wisdom served up by our nine justices.

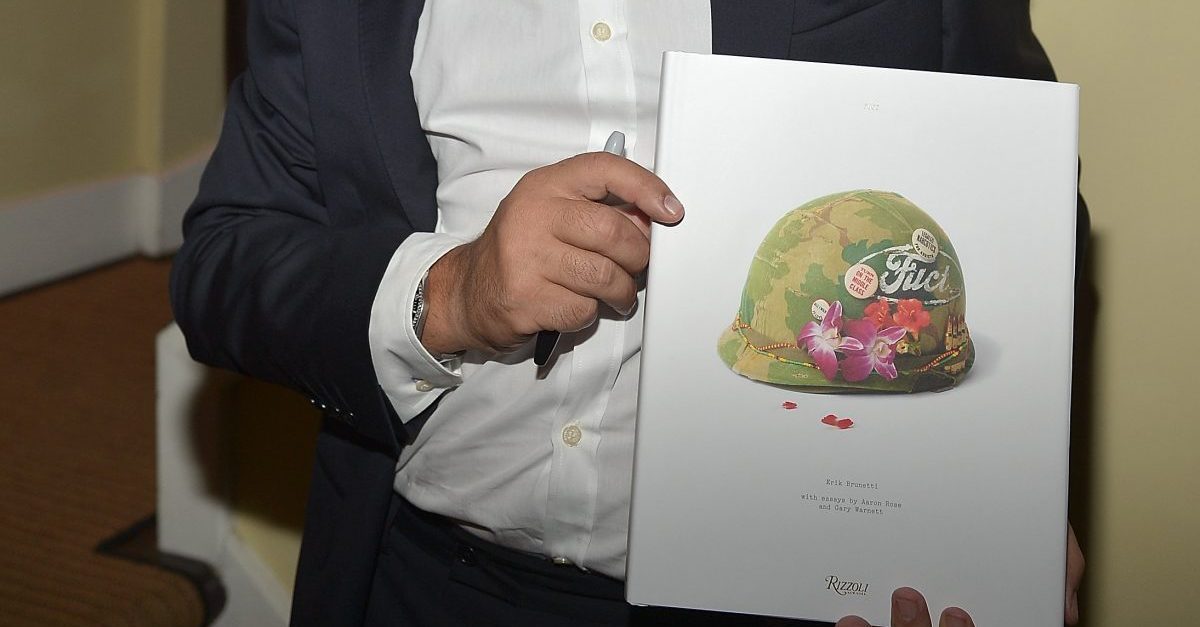

Some background on the case at bar: the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) denied trademark registration to artist Erik Brunetti, who attempted to register the name of his clothing line “FUCT.” The USPTO refused to issue the trademark protection on the grounds that under the “Scandalous Clause” in 15 U.S.C. 1052(a), it retains the right to bar protection of marks that would be too scandalous or immoral. According to Brunetti and his legal team (not to mention the Federal circuit – the appellate court that handles copyright, trademark, and patent disputes), the century-old Scandalous Clause is unconstitutional in that it violates the First Amendment.

The Government’s position? There’s nothing wrong with the law itself, or the USPTO’s application thereof. They say the office can legally refuse to issue legal protection to marks deemed scandalous on a “viewpoint-neutral basis.” As Solicitor General Noel J. Francisco argued in the government’s certiorari petition:

The scandalous-marks provision does not prohibit any speech, proscribe any conduct, or restrict the use of any trademark. Nor does it restrict a mark owner’s common-law trademark protections,” but rather limits the USPTO’s grant of extra legal benefits.

Those three little words can be awfully problematic, though. A “viewpoint-neutral basis” can be a tough thing to maintain when one is in the business of separating the proper from the lewd. Brunetti argued that the only reason the USPTO found his mark offensive was “because the Government concluded the mark meant “fucked,” and that it concluded that Brunetti “objectifies women,” engages in “extreme misogyny,” and “lack[s] in taste.” According to the brief, the USPTO found that Brunetti’s brand had a theme of “extreme nihilism—displaying an unending succession of anti-social imagery of executions, despair, violent and bloody scenes including dismemberment, hellacious or apocalyptic events, and dozens of examples of other imagery lacking in taste.” Reasonable minds might well disagree as to whether or not “FUCT” is a tasteful name for a clothing company – but it seems pretty clear that those arriving at either conclusion would do so via some content-based analysis.

In his petition agreeing that SCOTUS review would be helpful, Brunetti’s attorney made a point with which it’s tough to argue:

Marks that are cheerful and positive (e.g., Smiley Face) are granted, while viewpoints that are negative or controversial (e.g., middle finger-shaped bottle design) are refused. Marks about input into the digestive system are approved, while marks about output are rejected. Polite humor is fine, raunchy humor is scandalous. Raising babies is sweet, making babies is disgusting. Kissing is fine, sex is dirty. Feminism is good, misogyny is bad. The word PENIS is allowed, an outline of a penis is not …. In all these situations, the Government is preferring certain viewpoints over other, disfavored viewpoints.

Basically, we’re already about as far from “viewpoint-neutral” as we could get. And TBH, I really can’t wait to hear the questions the justices may raise.

Iancu v. Brunetti won’t be the first time SCOTUS has dealt with limitations of trademark protection; in 2017, Simon Siao Tam, the founder of a rock band called “The Slants” tried to register the band’s name with the USPTO, but was rejected on the grounds that the band’s name was disparaging toward people of Asian descent. Although “disparaging” differs from “scandalous,” the underlying concept is analogous, and the clause is the same. The rocker argued that the prohibition illegally interfered with his First Amendment rights, and both the Federal Circuit and SCOTUS agreed.

Given both the recent history and general common sense, Brunetti is likely to emerge as the winner. For those of you lamenting the deterioration of morality and language as “so 2019,” I present the following 1971 quote from Justice John Marshall Harlan, footnoted in Brunetti’s brief:

How is one to distinguish this [“fuck”] from any other offensive word? Surely the State has no right to cleanse public debate to the point where it is grammatically palatable to the most squeamish among us. …it is nevertheless often true that one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric.

Or to put it another way, the Scandalous Clause is FUCT.

[Image via Charley Gallay/Getty Images for RVCA]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.