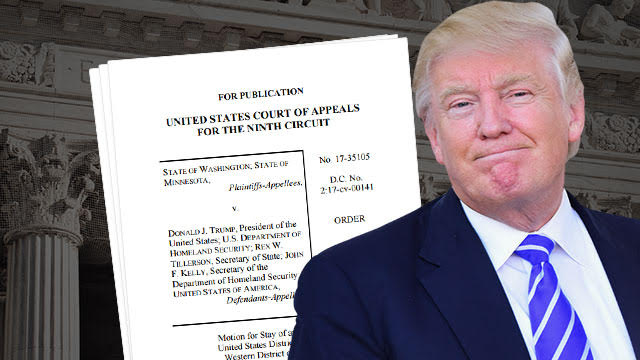

Even before the Ninth Circuit issued the decision upholding a temporary restraining order, President Donald Trump was blasting the judges, saying even a ‘bad student in high school’ would understand that the law supports his controversial travel ban which bars refugees all together and citizens from seven majority Muslim countries from entering the United States. When the judges published their decision Thursday night, Trump called it “disgraceful,” and said he would see everybody in court.

Even before the Ninth Circuit issued the decision upholding a temporary restraining order, President Donald Trump was blasting the judges, saying even a ‘bad student in high school’ would understand that the law supports his controversial travel ban which bars refugees all together and citizens from seven majority Muslim countries from entering the United States. When the judges published their decision Thursday night, Trump called it “disgraceful,” and said he would see everybody in court.

Last night, we provided a cheat sheet of how the three-judge panel threw some shade at the legal arguments Trump’s attorneys were using to reinstate the ban. But the truth is that upon closer examination of the 29-page opinion, credible legal experts from both sides of the aisle believe there are some major weaknesses with the decision presented by the Ninth Circuit against the Trump administration. In that vein, Trump is right!

Without getting too buried in the legal weeds, the weakest claims by the Ninth Circuit revolve around two areas: 1) the judges assert the courts can use Trump’s prior statements on the campaign trail to determine the (maybe bad?) motivation behind the law 2) the judges remarkably found that the states of Washington and Minnesota having standing to sue.

If Trump appeals the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, it is possible that the justices would come to a 4-4 decision which would effectively leave the 9th Circuit decision in place. But, it is also equally possible that one of the Justices could be swayed to Trump’s side based on some shaky principles put forward by the notoriously liberal-leaning Ninth Circuit.

“Look, this is not a solid decision. This is a decision that looks like it’s based more on policy than on constitutionality. There are many, many flaws,” Constitutional law expert Alan Dershowitz said during a recent television appearance.

Okay, so let’s break it down.

#1 — The court questionably suggests that Trump’s prior statements about a ‘Muslim Ban’ could be used to prove the discriminatory motive of the order.

The bottom line is this: Trump’s executive order does not explicitly say ANYTHING about banning Muslims in particular. Trump’s attorneys were pretty careful about that when they wrote it (yes, the seven countries named are Muslim majority, but many other countries were left off the list and also are Muslim majority). Plaintiffs (like the ACLU, CAIR, and others from across the country) are trying to urge courts to use Trump’s prior statements about wanting a “Muslim ban” as evidence that his executive order is discriminatory. They are especially pointing to an interview with former Trump advisor Rudy Giuliani as evidence. Guiliani claimed Trump asked him to put together a team to create a “legal” Muslim ban. The judges in the Ninth Circuit’s opinion don’t weigh in on whether the order is discriminatory itself, BUT they do seem to jump on board with the legal theory that campaign statements from Trump himself are fair game to prove motivation for the travel ban in the future. That’s troubling to some legal scholars.

“It is well established that evidence of purpose beyond the face of the challenged law may be considered in evaluating Establishment and Equal Protection Clause claims, ” the Ninth circuit judges wrote in their order.

But here’s the thing: it actually is not well-established law that courts can use campaign statements to prove religious discrimination. In fact, according to legal experts we consulted, courts rarely consider campaign statements at all.

Eugene Kontorovich, from the Northwestern School of Law, blasts the Ninth Circuit over this issue on the legal blog Volokh Conspiracy:

There is absolutely no precedent for courts looking to a politician’s statements from before he or she took office, let alone campaign promises, to establish any kind of impermissible motive. The 9th Circuit fairly disingenuously cites several Supreme Court cases that show “that evidence of purpose beyond the face of the challenged law may be considered in evaluating Establishment and Equal Protection Clause claims.” But the cases it mentions do nothing more than look at legislative history — the formal process of adopting the relevant measure. That itself goes too far for textualists, but it provides absolutely no support for looking before the start of the formal deliberations on the measure to the political process of electing its proponents.

For example, Kontrovich points to a 10th Circuit decision in which the court rejected the use of a district attorney’s campaign statements. “If campaign statements can be policed, the court concluded, it would in short undermine democracy” the court explained.

2) The court also seems to have a weak grasp on standing, experts contend.

The other YUGE issue is a bit less sexy, but equally important. It has nothing to do with the actual constitutionality of the executive order but could become a sticking point for the Supreme Court if Trump appeals to them. That is this: the Ninth Circuit’s shaky interpretation of standing. In order for plaintiffs (the states of Washington, Minnesota) to sue, they must show some kind of direct connection to harm that is redressable by the court. Lawsuits can’t just be brought because a group doesn’t like a law or executive order. Otherwise, every time there was a federal cut to school funding or a highway budget, a state might sue because they don’t like it.

Trump’s attorneys asserted that states don’t have standing because they are too far removed from any injury. State residents aren’t really being affected by the order, Trump’s DOJ contends. The Ninth Circuit disagreed, they found that the states had standing to sue the feds through harm to their State Universities. For example, the court said two visiting scholars at Washington State University were not permitted to enter the United States, and therefore this was enough to assert the rights of the students, scholars and faculty affected by the executive order. But some legal scholars think that legal interpretation is weak to say the least.

“The notion that states have standing to assert the rights of people entirely outside of the state seems absurd,” Kontorovich told LawNewz.com. Other legal scholars like Professor Alan Dershowitz agree with this assessment.

“It gives the State of Washington standing to raise constitutional issues on behalf of a family in Yemen who’ve never been to this country,” Dershowitz said on CNN, adding that this is the most extreme case of granting standing he’s ever seen.

Professor John Banzhaf from Washington University Law School recently explained:

Arguing that the EO (executive order) is “separating Washington families, harming thousands of Washington residents, damaging Washington’s economy, hurting Washington-based companies, and undermining Washington’s sovereign interest in remaining a welcoming place for immigrants and refugees” sounds quite conjectural, and contrary to established precedent for establishing legal standing.

The bottom line: don’t let the media fool you. This isn’t as clear cut of a case as many will make it out to be. There are many legal questions, and the Ninth Circuit order is far from crystal clear in their interpretation of how various laws apply. If Trump were to appeal to the Supreme Court, there are several areas where the Justices may agree with him.