Former President Donald Trump speaks at a rally at the Covelli Centre on September 17, 2022 in Youngstown, Ohio. (Photo by Jeff Swensen/Getty Images.)

Attorneys for former President Donald Trump on Tuesday filed a 40-page brief and an 87-page addendum in response to a U.S. Department of Justice request for a stay (or pause) of an ongoing special master review of documents seized from Mar-a-Lago on Aug. 8. The filing came shortly before the attorneys general of several Republican-led states file a motion in support of Trump in seeking the special master review.

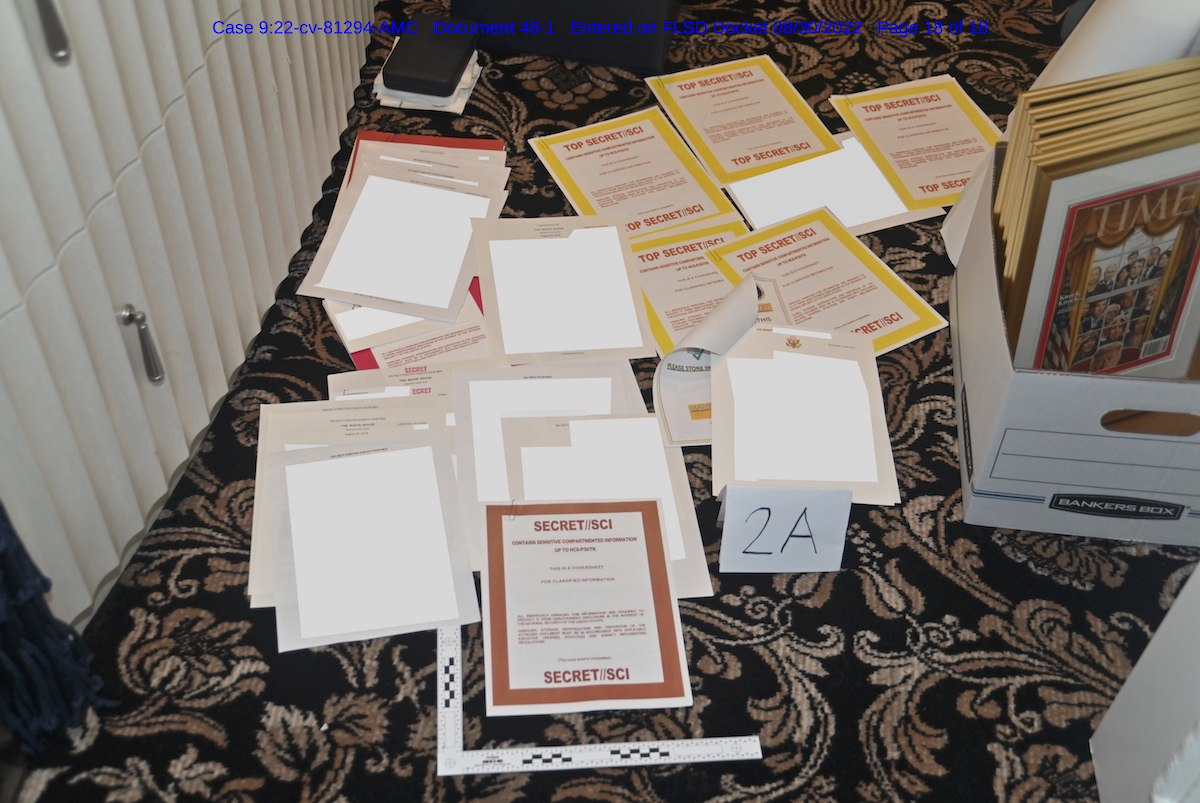

FBI agents on the aforementioned August date took a cache of materials from Trump’s palatial club and residence in Palm Beach, Florida; prosecutors claim some of the papers are classified at high levels.

Trump’s lawyers have attempted to assert various forms of privilege over some of the material — including executive privilege. They asked a district court judge, Trump appointee Aileen M. Cannon, to order an independent third party to review the material to assuage their concerns regarding privilege and to ascertain the extent of the classification alleged. U.S. District Judge Cannon appointed Judge Raymond Dearie as special master to effectuate that review. Dearie’s examination of the material is proceeding as a separate matter.

The DOJ asked Cannon to stay her ruling; she refused. The DOJ then appealed the matter to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. The stay was postured on the legal theory that while administrations may change, the Executive Branch is a single unit of government regardless of the occupant of the White House.

“The district court has entered an unprecedented order enjoining the Executive Branch’s use of its own highly classified records in a criminal investigation with direct implications for national security,” the DOJ wrote on Sept. 16.

In other words, according to the DOJ, one executive can’t claim privilege over a current executive.

The government argued that it was likely to succeed on the merits of proving the materials seized from Mar-a-Lago were, indeed classified; it also argued that Judge Cannon “erred by exercising jurisdiction as to records bearing classification markings.”

“The records bearing classification markings are not subject to any plausible claim of privilege that would prevent the government from reviewing and using them,” the government asserted.

The stay request, in essence, asked the circuit court to pause the special master review so that the DOJ could continue a “criminal-investigative” exam of the “seized records bearing classification markings.” It also asked to stay the demand that the government “disclose those records for a special-master review process.”

Federal prosecutors say FBI agents seized materials marked “secret” and “top secret” from Mar-a-Lago. The contents of the documents were redacted from the photo via the employment of white squares. (Image via an Aug. 31, 2022 federal court filing.)

Trump’s attorneys responded by attempting to turn some of the DOJ’s language on its head. They called the investigation into “the 45th President of the United States” both “unprecedented and misguided.”

The document didn’t refer to Trump as the “former” president until page 13.

Trump’s attorneys — James M. Trusty of Washington, D.C. and Christopher M. Kise of Tallahassee, Florida — repeated longstanding characterizations of the matter as nothing but a “document storage dispute that has spiraled out of control.”

“[T]he Government wrongfully seeks to criminalize the possession by the 45th President of his own Presidential and personal records,” Trump’s attorneys continued. “Recognizing the extraordinary circumstances presented by this case, the District Court determined that the appointment of a special master and entry of a limited injunction were ‘fully consonant’ with ‘the public interest, the principles of civil and criminal procedure, and the principles of equity.'”

Trump’s lawyers also balked that the government “unilaterally” claimed that some of the records seized from Mar-a-Lago were “classified.” Rather, Trump’s lawyers called the materials “purported” classified material.

“This Court should, respectfully, decline the Government’s invitation to proceed directly toward a preordained conclusion” about the classification of the documents, Trump’s lawyers continued. In essence, they asked the appellate court to question whether the materials were classified at all. Judge Cannon accepted a similar suggestion at the district court level to the bewilderment of many observers, since judges usually defer heavily to government assertions that documents are classified.

Trump’s attorneys told the appellate court that Cannon was “not inclined to hastily adopt the Government’s contention that the approximately 100 purportedly ‘classified’ documents were, in fact, classified, and that President Trump could not possibly have a possessory interest in any of them.”

The insinuation that the material may not be classified is at least mildly perplexing, since Trump’s attorneys on Sept. 19 — just one day earlier — told the special master that they preferred not to immediately argue whether or not the material was declassified. The relevant passage of that letter to Dearie reads as follows:

Similarly, the Draft Plan requires that the Plaintiff disclose specific information regarding declassification to the Court and to the Government. We respectfully submit that the time and place for affidavits or declarations would be in connection with a Rule 41 motion that specifically alleges declassification as a component of its argument for return of property. Otherwise, the Special Master process will have forced the Plaintiff to fully and specifically disclose a defense to the merits of any subsequent indictment without such a requirement being evident in the District Court’s order.

In their appellate motion, Trump’s attorneys cited Judge Cannon to opine that Dearie, “a Senior United States District Judge with FISA Court experience dealing with the most sensitive national security matters — was best suited to conduct an initial review of those documents.”

A footnote attempted to explain the distinction Trump’s lawyers were asserting:

The fact the documents contain classification markings does not necessarily negate privilege claims. For example, the partially unredacted search warrant affidavit states that certain documents with classification markings allegedly contain what appear to be President Trump’s handwritten notes. Those notes could certainly contain privileged information; further supporting the need for an independent, third-party review of these documents.

The government has stressed that its interest in ferreting out whether a crime was committed requires a stay to be issued. Specifically, prosecutors balked that Cannon banned the DOJ from “using the content of the documents to conduct witness interviews” or “reviewing the records to discern any patterns in the types of records that were retained, which could lead to identification of other records still missing.” A stay would allow those examinations to proceed post haste.

Trump’s lawyers countered via the Tuesday filing that any delay contemplated by the special master review would be minor: “it merely delays the investigation for a short period.”

Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate is seen on September 14, 2022 in Palm Beach, Florida. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.)

Cutting closer to the merits of the issue, Trump’s lawyers further asserted that the former president has a “possessory interest” in the records in question and returned to their belief that the DOJ was misapplying the relevant statutes in question. The government has long suggested that it was investigating potential violations of the Espionage Act — specifically, 18 U.S.C. §§ 793, 2071, and 1519. Trump’s lawyers have repeatedly offered that the dispute should center on another law, the Presidential Records Act, and again raised that argument via Tuesday’s appellate filing:

All government records (classified or otherwise) fall into two basic categories; they fall under the PRA or the Federal Records Act (“FRA”). “The FRA defines a class of materials that are federal records subject to its provisions, and the PRA describes another, mutually exclusive set of materials that are subject to a different, less rigorous regime. In other words, no individual record can be subject to both statutes because their provisions are inconsistent. Armstrong v. Exec. Office of the President, 1 F.3d 1274, 1293 (D.C. Cir. 1993).

Trump’s attorneys then distinguished between presidential records and personal records.

“The statute assigns the Archivist no role with respect to personal records once the Presidency concludes,” they noted while arguing that that the “responsibility” to designate a record as personal or presidential “is left solely to the President.”

“Accordingly,” Trump’s lawyers asserted, “all the records at issue in the Government’s motion fall into two categories: (1) Presidential records, governed exclusively by the Presidential Records Act; and (2) personal records, the determination of which was in President Trump’s discretion.”

“To the extent certain of the seized materials constitute Presidential records, a former President has an unfettered right of access to his Presidential records even though he may not ‘own’ them,” they went on.

A footnote suggests that the documents can go one of two places — but not to the DOJ:

What is clear regarding all of the seized materials is that they belong with either President Trump (as his personal property to be returned pursuant to Rule 41(g)) or with NARA, but not with the Department of Justice. However, it is not even possible for this Court, or anyone else for that matter, to make any determination as to which documents and other items belong where and with whom without first conducting a thoughtful, organized review.

To prevail, Trump’s attorneys said the government needed to demonstrate the following: (1) it is likely to prevail on the merits on appeal; (2) that absent a stay the Government will suffer irreparable damage; (3) that President Trump will suffer no substantial harm from the issuance of the stay; and (4) that the public interest will be served by issuing the stay. Plus, because the matter is now before an appellate court, the government must prove that the district court’s assessment of the matter was “clearly erroneous” as to the first element of the inquiry. If that occurs, the the government must also prove that the balance as to the remaining factors tips “heavily” in the government’s favor.

Trump’s attorneys say no such showings have been made and that the stay should therefore not be issued. Additionally, they argued that the special master’s appointment is a “pretrial procedure[]” that cannot be appealed at this stage of the case.

“Here, the Government has criminalized a document dispute and now vehemently objects to a transparent process that simply provides much-needed oversight,” Trump’s attorneys wrote in conclusion. “The Government’s attempt to shield the purportedly classified documents from the ambit of a Senior United States District Judge who served for seven years on a court dealing with the most sensitive national security matters therefore illustrates precisely why the District Court found a special master was appropriate and necessary under the circumstances.”

Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s residence at Mar-A-Lago, in Palm Beach, Florida, was photographed on August 9, 2022. (Photo by Giorgio Viera/AFP via Getty Images.)

Not long after Trump’s attorneys filed the motion, representatives for the states of Texas, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Montana, Louisiana, South Carolina, Utah, and West Virginia filed a 21-page document as amici curiae to support Trump’s legal positions.

The Republican-led states employed phraseology that not even Trump’s attorneys dared to use in their own motion.

The amici states referred to the underlying situation as the “Biden Administration’s unprecedented nine-hour search” of Mar-a-Lago. The document further claims the Biden Administration was caught “ransacking the home of its one-time—and possibly future—political rival.”

The amici — led nominally by William F. Cole, the assistant solicitor general of Texas — framed the issue as a political dispute by a Democratic administration they collectively loathe:

Throughout this litigation the Biden Administration has attempted to trade on the reputation of the Department of Justice and the Intelligence Community to thwart the appointment of a neutral special master. But the district court twice rejected that gambit, and this Court should too. Amici States have been frequent litigants against the Biden Administration, and they offer this amicus brief to highlight how the Administration’s conduct in connection with this case is of a piece with the gamesmanship and other questionable conduct that have become the hallmarks of its litigating, policy-making, and public-relations efforts. At a minimum, this Court should view the Administration’s assertions of good-faith, neutrality, and objectivity through jaundiced eyes. Consequently, this Court should reject the Administration’s request to stay the district court’s order pending appeal and instead permit this document dispute to proceed before a neutral special master.

Some of the cases cited as alleged grounds for Biden administration gamesmanship include Texas v. Biden, 20 F.4th 928, 941 (5th Cir. 2021), a case decided by two Trump appointees and one George H. W. Bush appointee that was later (and admittedly) vacated on other grounds by the U.S. Supreme Court. The amici claimed that the following was the issue in that case:

The Biden Administration appealed that final judgment, but just two business days before oral argument in the Fifth Circuit, it issued two new memoranda purporting to supersede the already-vacated ones. Hours later, it filed a twenty-six-page motion arguing that the case was moot and that the Administration was entitled to vacatur of the district court’s order—the precise remedy it had hoped to obtain on appeal.

Other alleged acts of gamesmanship by the Biden Administration were cited in the areas of immigration law, administrative law, the Covid-19 pandemic — including the eviction moratorium and vaccine mandate.

Left unsaid by the amici was that the original eviction moratorium occurred during the Trump administration. Also left unsaid was that Trump has vociferously defended the vaccines being given emergency approval by his administration — though he has slammed mandates that require people to take them.

The amici complained about reports that the Biden Administration was working with social media companies to combat so-called “disinformation.” They further complained about whether the federal government funded research at China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology.

The upshot, according to the amici, is that the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals should not trust Biden’s DOJ:

The Biden Administration’s track record supports the district court’s refusal to credit the Administration’s ipse dixit about the contents of documents it seized during its raid of President Trump’s private residence. Under the extraordinary circumstances of this case, the court correctly set aside the presumption of regularity usually afforded to government officials. This Court should affirm that careful decision.

The Trump filing and the amici filing are both embedded below:

[Editor’s note: legal citations have been omitted from a few quotes in this piece.]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]