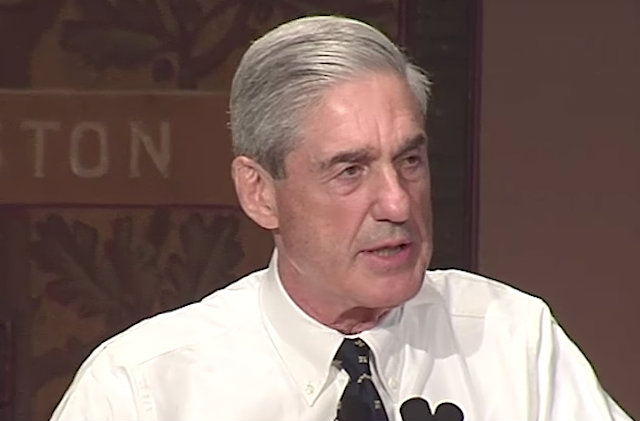

Special Counsel Robert Mueller chose to prosecute ex-Trump aides Paul Manafort and Rick Gates under a rarely used statute — rarely used because the law could bring up major First Amendment right to free speech concerns.

The core charges against Manafort & Gates concern section 612 of Title 22 of the United States Code, colloquially known as the Foreign Agents Registration Act, a statute invented in the middle of World War Two, and meaningfully unamended since 1966, at the peak of the Cold War. This war-propaganda relic of a statute has seen only one criminal conviction in its fifty-year history since 1966. There is a reason for that: the statute is frighteningly broad, and should be considered unconstitutional for vagueness and violating the First Amendment free speech rights of American citizens, especially given the number of innocent people that could be wrongfully prosecuted tomorrow under this statute. Does anyone really think once this box of criminal punishment laws is opened, the government will stop at Manafort & Gates?

Consider how loosely and liberally the law can be defined: “any person” who “acts in any other capacity” merely “at the request” of a “foreign principal” can be criminally prosecuted if they merely “engage within the United States in political activities” thought to be “in the interests” of a “foreign principal.” Guess who a “foreign principal” is? Pretty much anybody that is not a citizen of the United States. In sum, anyone who acts politically in the interest and at the request of a non-citizen, must register, or risk ten years in prison.

What does that mean? It means everyone who acts “in the interest” of Dreamers “at the request” of Dreamers must register as a foreign agent, or face federal prison time. Under this absurdly broad statute, Jesse Jackson and Jimmy Carter could go to prison for peace-related foreign initiatives that include unofficial diplomatic activities (as both have successfully achieved in the past).

Think about it — ever engaged in any political activity in America that could be labelled “at the request” of a non-citizen? Could a simple retweet of a foreigner count? How about a simple share on Facebook? A simple act on behalf of someone you know from overseas in response to “hey, somebody should say something about this”? The number of unsuspecting people that could get ensnared, trapped and caught up in the criminal dragnet is why prosecutions under this statute are so exceedingly rare.

The criminal counterpart to the ominous sounding “foreign agent” registration statute is section 618 of Title 22 of the United States Code, which allows for criminal prosecution of any “willful” violation of either the statute or any of the regulations that percolate under it. As courts routinely rule, a willfulness component cannot save the Constitutionality of a vague law, and, while unexamined meaningfully in our courts to date, the Foreign Agents Registration Act is just such a vague, invasive, free-speech burdening, unconstitutional law.

FARA-predicated criminal prosecutions pose another risk beyond vagueness under the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause: they require public registration of private speech by Americans. The Supreme Court long ago recognized the right of anonymous speech, and the state’s limited right to curtail that speech. Requiring registration for political speech merely because that speech is “at the request” of a non-citizen invades the First Amendment right to express yourself anonymously.

As Justice Stevens wisely opined in a seminal Supreme Court holding protecting anonymous speech: Anonymity “exemplifies the purpose behind the Bill of Rights and of the First Amendment in particular.” In an era of doxxing one’s political opponents, anonymity has taken even greater purpose and importance. Registration with the federal government invades that anonymity. If, as the Supreme Court held, Ohio cannot require registration of distributed leaflets, or even disclosure of the publisher’s names on those leaflets, then how can the United States compel far more invasive registration and public disclosure of speech merely because that speech may be “at the request” and “in the interest” of somebody who is not a citizen? It’s still the speech of an American citizen that is being restricted and, potentially, criminally punished. And that is precisely what both the First Amendment and Fifth Amendment forbid.

This raises more than Fifth Amendment due process questions; it raises First Amendment speech problems. Mueller has opened a Pandora’s Box that can only be effectively closed with a court dismissal of at least parts of the indictment against Manafort & Gates.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.