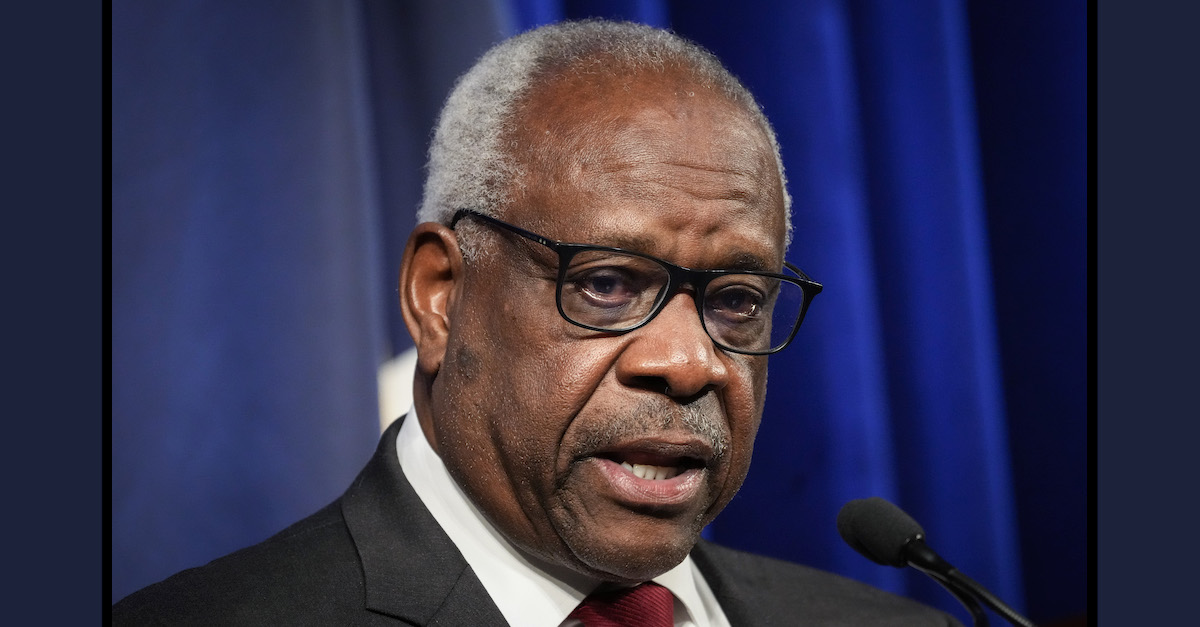

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas speaks at the Heritage Foundation on October 21, 2021 in Washington, DC.

The Supreme Court of the United States on Thursday ruled that the “Constitution does not require Congress to extend SSI [Supplemental Security Income] benefits to residents of Puerto Rico” in an opinion in which Sonia Sotomayor was the sole dissenting justice. However, a concurrence by Justice Clarence Thomas — which seeks to split several common understandings of the Fifth and 14th Amendments — has attracted some attention.

The crux of the case was summed up in a case syllabus as follows:

[R]espondent Jose Luis Vaello Madero received SSI benefits while he was a resident of New York. He then moved to Puerto Rico, where he was no longer eligible to receive those benefits. Unaware of Vaello Madero’s new residence, the Government continued to pay him SSI benefits. The Government eventually sued Vaello Madero to recover those errant payments, which totaled more than $28,000. In response, Vaello Madero invoked the Constitution, arguing that Congress’s exclusion of residents of Puerto Rico from the SSI program violated the equal-protection component of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

The majority opinion, written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett.

Thomas and Gorsuch concurred via separate opinions.

“For various historical and policy reasons, including local autonomy, Congress has not required residents of Puerto Rico to pay most federal income, gift, estate, and excise taxes,” Kavanaugh wrote. “Congress has likewise not extended certain federal benefits programs to residents of Puerto Rico.”

Benefits were not required, Kavanaugh wrote, “[i]n light of the text of the Constitution, longstanding historical practice, and this Court’s precedents.”

Kavanaugh, while noting that the U.S. has five territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, the U. S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico), explained the situation at length as follows (we’ve eliminated most of the legal citations):

The Territory Clause of the Constitution states that Congress may “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory . . . belonging to the United States.” Art. IV, §3, cl. 2. The text of the Clause affords Congress broad authority to legislate with respect to the U. S. Territories.

Exercising that authority, Congress sometimes legislates differently with respect to the Territories, including Puerto Rico, than it does with respect to the States. That longstanding congressional practice reflects both national and local considerations. In tackling the many facets of territorial governance, Congress must make numerous policy judgments that account not only for the needs of the United States as a whole but also for (among other things) the unique histories, economic conditions, social circumstances, independent policy views, and relative autonomy of the individual Territories.

Of relevance here, Congress must decide how to structure federal taxes and benefits for residents of the Territories. In doing so, Congress has long maintained federal tax and benefits programs for residents of Puerto Rico and the other Territories that differ in some respects from the federal tax and benefits programs for residents of the 50 States.

On the tax side, for example, residents of Puerto Rico are typically exempt from most federal income, gift, estate, and excise taxes. At the same time, residents of Puerto Rico generally pay Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment taxes.

On the benefits side, residents of Puerto Rico are eligible for Social Security and Medicare. Residents of Puerto Rico are also eligible for federal unemployment benefits.

But just as not every federal tax extends to residents of Puerto Rico, so too not every federal benefits program extends to residents of Puerto Rico.

Citing Califano v. Torres and Harris v. Rosario, which Kavanaugh and the majority said “dictated” the result, the Court used rational basis review to hold — in essence — that Vaello Madero was not entitled to the SSI benefits received while he lived in Puerto Rico.

“Puerto Rico’s tax status — in particular, the fact that residents of Puerto Rico are typically exempt from most federal income, gift, estate, and excise taxes — supplies a rational basis for likewise distinguishing residents of Puerto Rico from residents of the States for purposes of the Supplemental Security Income benefits program,” Kavanaugh wrote.

Rational basis review applies when no fundamental rights (marriage, privacy, contraception, interstate travel, and procreation — just to name a few) are at play and when no suspect classifications (race, religion, national origin, and alienage) are involved in the matter.

A ruling in favor of Vaello Madero, Kavanaugh wrote, would “presumably” force Congress “to extend not just Supplemental Security Income but also many other federal benefits programs to residents of the Territories in the same way that those programs cover residents of the States.”

Additionally, the relatively new justice noted, the government would necessarily be required to “inflict significant new financial burdens on residents of Puerto Rico, with serious implications for the Puerto Rican people and the Puerto Rican economy.”

“The Constitution does not require that extreme outcome,” Kavanaugh and the majority indicated.

The 6-page majority opinion (the 2-page syllabus doesn’t technically count) wrapped up a note about federal policy:

The Constitution affords Congress substantial discretion over how to structure federal tax and benefits programs for residents of the Territories. Exercising that discretion, Congress may extend Supplemental Security Income benefits to residents of Puerto Rico. Indeed, the Solicitor General has informed the Court that the President supports such legislation as a matter of policy. But the limited question before this Court is whether, under the Constitution, Congress must extend Supplemental Security Income to residents of Puerto Rico to the same extent as to residents of the States. The answer is no. We therefore reverse the judgment of the U. S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.

Justice Thomas concurred but wrote separately to sketch his thoughts about whether the “Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment contains an equal protection component whose substance is ‘precisely the same’ as the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” (He now “doubt[s]” that it does, though he admitted he believed the two were synonymous in the past.) Thomas’s traipse through the annals of history took 15 pages to explain and contained significant discussions about citizenship (as contemplated by the 14th Amendment), slavery, an analysis of Plessy v. Ferguson (the since-rubbished 1896 case which held that separate-but-allegedly-equal laws did not violate the 14th Amendment) and an analysis of the Dred Scott decision (the since-scuttled 1857 case that held that the children of slaves were not American citizens and could not sue in federal court).

Thomas wrote:

Even if the Due Process Clause has no equal protection component, the Constitution may still prohibit the Federal Government from discriminating on the basis of race, at least with respect to civil rights. While my conclusions remain tentative, I think that the textual source of that obligation may reside in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. That Clause provides: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Amdt. 14, §1, cl. 1.

“While the historical evidence above is by no means conclusive,” Thomas continued, “it offers substantial support for the proposition that, by conferring citizenship, the Citizenship Clause guarantees citizens equal treatment by the Federal Government with respect to civil rights.”

A footnote connects the argument to the instant case about SSI benefits:

Adopting this understanding of the Citizenship Clause necessarily prompts additional questions. For example, beyond prohibiting racial discrimination with respect to civil rights, what other forms of discrimination does the Citizenship Clause proscribe? Is access to government benefits a “privilege” or “immunity” of citizenship—i.e., a civil right?

The question remained open, however; and many scholars zeroed in on this passage from Thomas:

Bolling reasoned that the “liberty” protected by the Due Process Clause covers “the full range of conduct which the individual is free to pursue,” 347 U. S., at 499–500, and therefore guaranteed freedom from segregated schooling. That understanding of “liberty” likely sweeps too broadly. Given the relevant history, “it is hard to see how the ‘liberty’ protected by the [Due Process Clause] could be interpreted to include anything broader than freedom from physical restraint.” Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U. S. 644, 725 (2015) (THOMAS, J., dissenting). And even if “liberty” encompasses more than that, “[i]n the American legal tradition, liberty has long been understood as individual freedom from governmental action, not as a right to a particular government entitlement.” Id., at 726; see also C. Green, Seven Problems With Antidiscrimination Due Process, 11 Faulkner L. Rev. 1, 32 (2019) (“Even on [a] very expansive view, ‘liberty’ is still only freedom from interference, rather than positive rights to receive benefits or participate in others’ activities”). Consequently, if “liberty” in the Due Process Clause does not include any rights to public benefits, it is unclear how that provision can constrain the regulation of access to those benefits.

As a whole, though, Thomas’s concurrence basically argued that the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause isn’t as strong as people might think — but the 14th Amendment is just as strong and perhaps maybe even stronger on the same precise points up for debate.

Justice Gorsuch issued a 10-page concurrence to rubbish a group of other cases:

A century ago in the Insular Cases, this Court held that the federal government could rule Puerto Rico and other Territories largely without regard to the Constitution. It is past time to acknowledge the gravity of this error and admit what we know to be true: The Insular Cases have no foundation in the Constitution and rest instead on racial stereotypes. They deserve no place in our law.

Gorsuch also noted that “no party” to the instant case asked the Court to overrule those matters — so the more majority opinion failed to directly overrule the Insular Cases in whole.

Justice Sotomayor’s 10-page dissent said she found “no rational basis” to treat some U.S. citizens different from others:

The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program pro- vides a guaranteed minimum income to certain vulnerable citizens who lack the means to support themselves. If they meet uniform federal eligibility criteria, recipients are entitled to SSI regardless of their contributions, or their State’s contributions, to the United States Treasury, which funds the program. Despite these broad eligibility criteria, today the Court holds that Congress’ decision to exclude citizen residents of Puerto Rico from this important safety-net pro- gram is consistent with the Fifth Amendment’s equal protection guarantee. I disagree. In my view, there is no rational basis for Congress to treat needy citizens living anywhere in the United States so differently from others. To hold otherwise, as the Court does, is irrational and antithetical to the very nature of the SSI program and the equal protection of citizens guaranteed by the Constitution. I respectfully dissent.

Addressing the rational basis reasoning employed by the majority, Sotomayor wrote that the standard was “deferential” but not “toothless.” In her opinion, “Congress’ decision to exclude millions of U. S. citizens who reside in Puerto Rico from the SSI program fails even this deferential test.”

The full syllabus, the majority opinion, the concurrences, and the dissent are all embedded in the same document below:

[Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.]