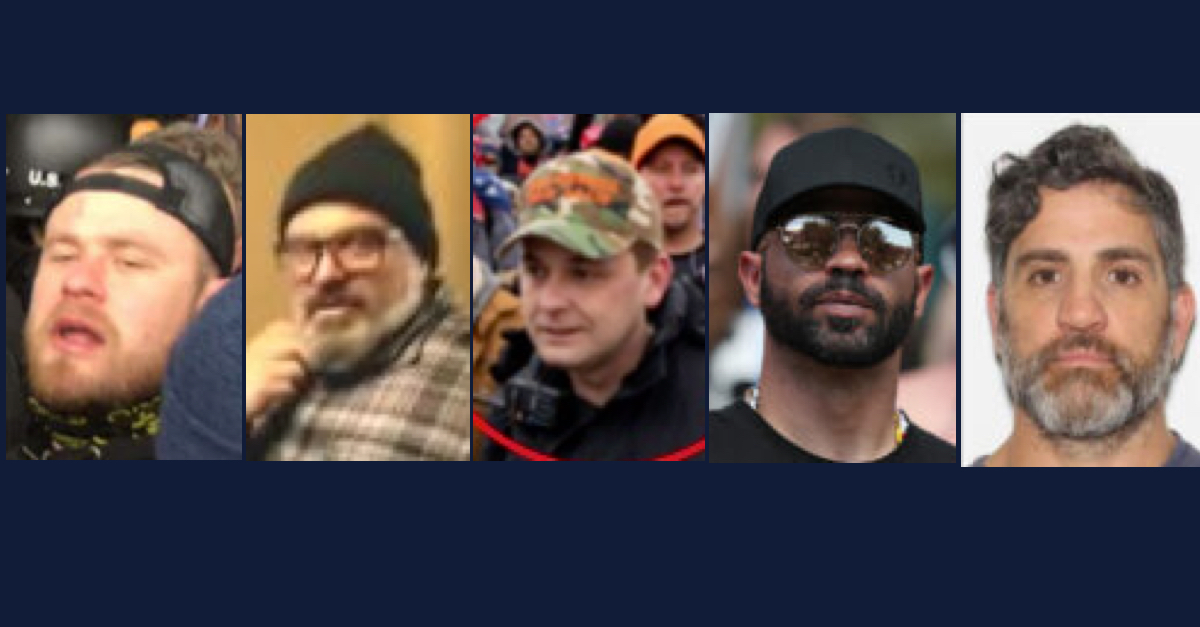

Left to right: Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, Enrique Tarrio, Dominic Pezzola, defendants in the Proud Boys Jan. 6 conspiracy case (images via FBI court filings).

A federal judge rejected an 11th hour claim by Proud Boys’ lawyers that prosecutors improperly discriminated against white jurors. The ruling, made by a Donald Trump appointee, will ensure that the jury panel will bear a greater resemblance to the diverse U.S. capital city.

The Proud Boys describe themselves as a “Western chauvinist” group, but hate group monitors say the groups leaders and members have flirted with — and even outright embraced — antisemitic, bigoted and white supremacist ideas.

Their leader Enrique Tarrio, who is the lead defendant, emphasizes his own Latino background, but he was convicted of burning a “Black Lives Matter” banner stolen from an historic Black church in December 2020, days before the U.S. Capitol attack.

After ten days of often plodding and, at times, rocky voir dire, Nicholas Smith, attorney for Ethan Nordean — who is facing more than a dozen charges relating to the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol — challenged the government’s use of peremptory challenges in the jury selection process. He said that because the government used their challenges to oust five white men and one white woman from the jury pool, prosecutors had improperly discriminated on the basis of race, gender, and religion.

The challenge came after the lawyers in the case had finally whittled the panel down to the 12 deliberating jurors and four alternates who will decide the fates of Tarrio, Zachary Rehl, Dominic Pezzola, Joseph Biggs, and Nordean. The five men are accused of plotting to use force to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden‘s 2020 electoral win on Jan. 6, 2021, when hordes of Donald Trump supporters, angry over losing the election, swarmed the U.S. Capitol building. The riot caused an estimated $2.7 million in damage and forced lawmakers and staff to either evacuate the building or shelter in place.

The jury selection process began before Christmas. Kelly has indicated that he will swear the jury in on Wednesday, when opening statements are expected to begin.

“This Is Disturbing”

The defense’s Batson challenge — so named for a 1986 Supreme Court case ruling that found discriminatory use of peremptory challenges by criminal prosecutors is unconstitutional — came just as it appeared that the final jurors had been selected.

Smith said that the prosecution’s decision to cut multiple “white, male Republican[s],” as well as a Roman Catholic priest, from the panel amounted to discrimination.

“None of these jurors expressed any sympathy for rioters or Donald Trump,” Smith said, later adding: “There is no possible explanation that I can think of for cutting these jurors except for prohibited characteristics.”

Smith argued that there were no indications that the eliminated jurors would be biased in favor of the defendants. He praised each potential juror’s apparent even-handedness and neutrality, describing one of the jurors — a Roman Catholic priest — as “supremely objective” and dispassionate.

“This is disturbing,” Smith said. “Six of the eight were white jurors, five of those 6 were male. The statistics are 75% and over 80%.” Smith added that those numbers alone show that the government was discriminating.

U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly, a Trump appointee, indicated that he wasn’t quite buying the defense’s argument, but instructed prosecutors to explain why they rejected those jurors.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Jason McCullough offered a range of reasons as to why each specific juror was eliminated.

One, McCullough said, indicated he might be “sympathetic to the defendants’ views on Antifa.” Another juror, who came to jury selection “dressed in a full suit,” raised concerns that his “composure, his professional status could cause other jurors to add undue weight to his role in the deliberations” and that he could “take control of a jury panel.”

As to the priest, McCullough said that there was a concern that he would “bring his line of work into the jury room” and that “defense attorneys might seek to exploit his occupation by appealing to his sense of redemption or equity.”

Smith argued that the government’s reason was obvious religious discrimination. Kelly disagreed.

“Having a concern about a juror having professional experience, for some reason — whatever the reason is — [that] would exercise undue influence over the other jurors, that is a very common concern to have about a jury,” the judge said.

In the end, Kelly rejected the defense’s arguments. He found that the demographic distribution of the government’s peremptory challenges aligned closely with the demographics of the jury pool itself, and said that the defense hadn’t successfully made its case that discrimination had occurred. According to the latest Census, Washington, D.C. has a population that leans slightly toward people of color by plurality, with just under 46 percent of the population describing themselves as either Black or white alone.

“This isn’t a situation at all where the effect of these peremptories is to render the jury bereft of white people or men,” Kelly said.

The Batson challenge was not particularly surprising, considering that the voir dire process in this case has been highly contentious from the start. The five defense attorneys have either objected to, or wanted further questioning of, nearly all of the potential jurors, requesting that Judge Kelly do more to suss out potential disqualifying bias.

At one point, a defense attorney wanted Kelly to investigate a potential juror’s work in economic policy, apparently skeptical that the juror may link capitalism to systemic oppression in a way that was prejudicial to his client. Judge Kelly rejected this request.

Attorney Norm Pattis, whose law license in Connecticut was recently suspended in connection with his defense of right-wing conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, had repeatedly called the voir dire process an “unendurable farce.” The process was so contentious that when a juror was qualified without objection from either side, Kelly’s courtroom deputy jokingly said that it was as if lighting had struck.

“So How Do You Think the Case Is Going?”

Monday began with a juror asking the judge to be dismissed from the jury pool. He explained to Kelly that since being called as a potential panelist, he has suffered increased anxiety, reminiscent of what he described as previous “job stress” that was so severe that he required medication. The juror said that he feared for the safety of himself and his family should he be on a jury that winds up convicting the high-profile Proud Boys members, and asked that he be released.

Kelly complied and excused the juror from the pool. Defense attorneys argued that the man’s request was indicative of larger problems.

“This is the second juror who is very concerned about the safety of his family,” Tarrio attorney Sabino Jauregui said, later adding: “This jury pool is tainted. [They] have been talking to each other […] it’s very prejudicial to us, a presumed prejudiced that [people are] afraid for their lives [and] families.

“There’s no reason to think the jurors are talking about this at all,” Kelly said in response, adding that the man who asked to be dismissed was a singular situation and didn’t implicate the rest of the jury pool.

Juror issues continued after the lunch break, when one potential juror told Judge Kelly that he had been approached in the cafeteria by someone who appears to have been a reporter. Kelly, after reminding the courtroom that he has issued an order prohibiting press and attorneys from contacting jurors during the pendency of the trial, brought the juror in for questioning.

“I was sitting with another juror and he took off to take a walk,” the juror told the judge. “A woman came up to me and said, ‘So how do you think the case is going?’ I said I don’t think we’re supposed to talk, and she said ‘Well, it was worth shot.’ She lingered, and I said ‘Sorry.'”

The juror then pointed out the person who approached him: she was sitting in the courtroom. Prosecutors later identified her as a reporter who has interviewed a spouse of one of the defendants and one of the defense attorneys, although her name was not provided.

Kelly, apparently satisfied that no prejudice would result from the interaction, noted that “there are inadvertent things that happen,” but that approaching a juror in this way was not one of them. He then issued a stern warning.

“I have issued an order related to the media that they are not to approach the jurors in this case while their service is pending,” Kelly said. “The failure to observe that order could result in a finding of contempt, and it could, in theory, result in criminal prosecution, depending on what was said to the juror. I want to make sure that everyone is clear that no one is to approach these jurors or, once we have a jury, that no one is to approach them about the case.”

Kelly added that anyone who approaches jurors does so “at their peril.”