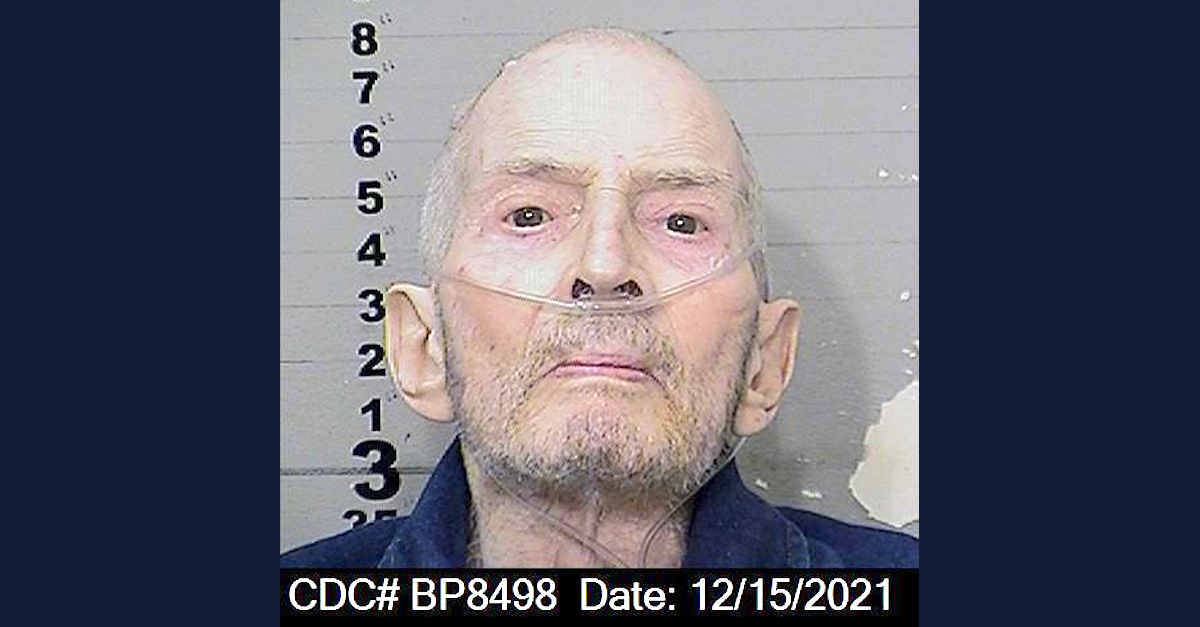

Convicted murderer Robert Durst appears in a Dec. 15, 2021 mugshot released by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

For nearly 40 years, Robert Durst avoided prosecution over the death of his missing wife Kathleen McCormack Durst, and the now-convicted murderer’s death a little more than a week ago sank any chance for prosecution on the indictment against him filed on Nov. 1.

Durst’s death also will inevitably waive his conviction, owing to what has been described as an “unfortunate technical rule” about the second-order effect of his pending appeal when he died at age 78.

On Wednesday, the top prosecutor in New York’s Westchester County—the jurisdiction where the Dursts called home before McCormack turned up missing—broke her silence about the reason for the almost four-decade delay.

The long road to justice against the now-deceased real estate heir was winding and indirect. In 1982, McCormack disappeared at the age of 29 and would later be presumed dead. Decades would pass before Durst would be charged with murder: of other people. Durst was acquitted of murdering his Texas neighbor Morris Black in 2003, before a California jury convicted him of killing 55-year-old friend Susan Berman.

In the prior cases, prosecutors argued that Durst killed others to cover up McCormack’s disappearance. Westchester County District Attorney Mimi Rocah said in a press conference Tuesday that Durst’s conviction in Berman’s murder armed her prosecutors with what they needed to indict.

Kathleen’s family, however, said through an attorney that the D.A.’s office did not invite them to the press conference—or even tell them it was going to happen.

As authorities said in the California trial, Durst had Berman pretend to be Kathleen in a 1982 call to the missing woman’s medical school, which mislead New York investigators, Rocah said. Also, Westchester County prosecutors could now show evidence that Durst confessed to Berman that he murdered his wife. Investigators in the early investigation also developed tunnel vision, ignoring red flags that showed Durst was lying, according to the D.A.

The 78-year-old recently died of cardiac arrest. His defense attorneys long made much of his ailing health. They said he had cancer, and they tried to stall the trial over it. Durst planned on testifying, and they worried about the strain on his condition. Nonetheless, he appeared engaged when he finally took the stand, giving detailed accounts, although he spoke very slowly.

“That’s a full-service law firm,” he quipped at one point about his attorneys.

Jurors did not believe what he had to say about finding Berman already dead at her Beverly Hills home on Dec. 23, 2000. They convicted him of first-degree murder for fatally shooting her, execution-style. He did it in order to silence her about him murdering Kathleen, in light of the Westchester County D.A.’s office reopening the case that year.

That was more than 20 years ago. Rocah said that investigators in the early stage of the case developed tunnel vision, basing their work on Durst’s lie that he drove her to the train to New York City, where she went to medical school. They focused their case on Manhattan when they should have been focused outside, missing the opportunity to get physical evidence, she said.

Rocah said red flags were apparent early on in the search. Evidence of domestic violence by Durst against Kathleen, witness statements, and physical evidence at the Westchester County home all contradicted his statements to investigators at the time, she said. The D.A. credited investigator Joseph Becerra with moving the case forward two decades ago, and also highlighted the work of more recent officials in doing the work to get a formal charge of murder in the second degree.

“And yet the focus of the investigation remained guided by Durst’s version of events that he had driven her to the train to New York City on the night she disappeared,” Rocah said. “Most significantly, reports that eyewitnesses had placed Kathleen in Manhattan were debunked only after New York State police investigator Joseph Becerra got involved in the investigation almost 20 years later. Further, in the initial investigation, great reliance was placed on a phone call supposedly placed by Kathleen to her medical school after her disappearance, which falsely suggested she was still alive. Many years later, evidence was developed that showed that this call was in fact a ruse that Durst had orchestrated using his friend Susan Berman. As we now know, Durst later murdered Berman in December of 2000 in order to keep her silent, and he was ultimately arrested by authorities in California in 2015 and successfully prosecuted for that murder. That conviction had significant implications for our office’s ability to bring charges.”

Kathleen McCormack Durst was declared legally dead in 2017. Family attorney Robert Abrams reiterated claims that defendant Durst’s family helped him dodge prosecution for all these years, and he demanded Rocah’s resignation.

“Had the McCormack family been invited to today’s press conference, they would have explained not only the impact that Kathie’s murder has had on their lives, but also the damage that has resulted from law enforcement’s failure to treat the victims of this crime as equal before the law,” he said.

Elected in late 2020, Rocah assumed office last year, and she brought charges that winter.

A spokesperson for family-owned Durst Organization has said Abrams has been making unsubstantiated claims.

“Mr. Abrams has a long history of leveling hollow, baseless attacks without ever providing a single shred of documentation to substantiate his wild claims,” Jordan Barowitz said in a statement to The Associated Press in a Saturday report. “Time and time again, these accusations have been summarily dismissed and thrown out by the courts.”

Read her report, below:

[Prison photo via California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.]