After barely four hours of deliberations, a jury told a federal judge on Thursday morning that it appeared deadlocked on a key count against Michael Avenatti, which at least in theory, would have the potential to scuttle both of the charges against him.

“We are unable to come to a consensus on count one,” the note read, referring to the wire fraud charge. “What are our next steps?”

U.S. District Judge Jesse Furman gave the jury a variation of the so-called Allen charge, instructing them to get back to work.

“Essentially a Gift”

Avenatti stands accused of having defrauded his most famous client, Stormy Daniels, out of $300,000 of her $800,000 advance on a book titled “Full Disclosure,” a memoir and account of her litigation over her alleged affair with former President Donald Trump. Prosecutors say that Avenatti misled Daniels for months, falsely claiming that publisher St. Martin’s Press and agency Janklow & Nesbitt never forwarded the money.

In fact, prosecutors say, they sent the money to Avenatti, and he spent it before stringing Daniels along for months in text messages entered into evidence. Avenatti also allegedly forged the adult film actress’s signature, helping to form the basis of a separate aggravated identity theft charge.

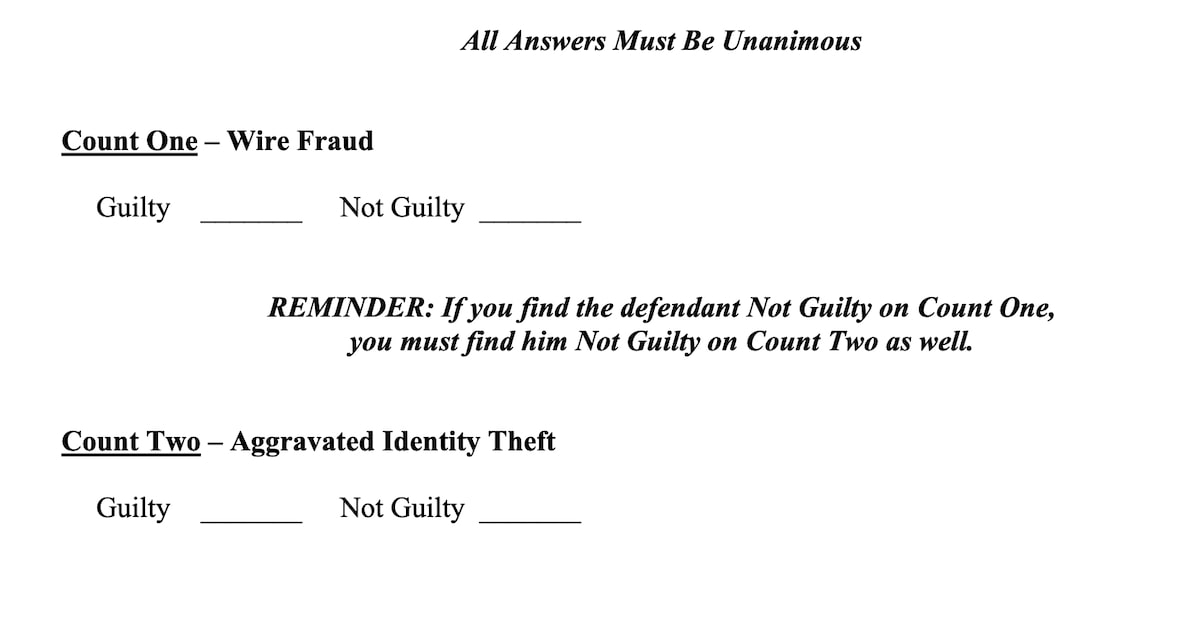

Carrying a penalty of up to 20 years, wire fraud is the top charge, but it’s also one on which both counts of the indictment hinge. The jury’s verdict sheet instructs them to disregard the second count if they find Avenatti not guilty on the first.

A screenshot from the verdict sheet in Michael Avenatti’s criminal case for allegedly defrauding Stormy Daniels.

If the jury disregards that instruction, however, there may be little that Avenatti can do about it.

Attorney Mitchell Epner, a former federal prosecutor who is now of counsel with the firm Rottenberg Lipman Rich PC, notes that the 1984 Supreme Court precedent of U.S. v. Powell held that inconsistent verdicts are to be accepted.

“Juries usually deliver consistent verdicts, but not always,” Epner told Law&Crime, noting that the precedent accounts for “horse-trading” that sometimes takes place in jury rooms during divided deliberations.

If the jury delivers an inconsistent verdict by acquitting on the first count and convicting on the second, Epner said: “The rule set down by the Supreme Court is that the defendant should take and should perceive the not guilty verdict as essentially a gift from the jury.”

“A Complete Defense”

Sometimes described as a “dynamite” charge, an Allen charge is a sometimes-controversial instruction from a judge telling deadlocked jurors to reconsider their own views and those of their peers. The judge also typically urges them not to abandon their honest beliefs only to reach a verdict.

“Jurors who I have spoken to have told me that they feel coerced by [it] because they feel as if what the judge is telling them is ‘you don’t get out of here without a verdict,’ even though those aren’t the words that are said,” Epner noted.

The jury’s first note surprised many because it arrived early during their deliberations, long before most panels typically declare a deadlock. Another note sent later in the day asked to scrutinize the transcript of testimony by Daniels, the star witness.

It also requested clarification on a definition at the heart of Avenatti’s defense: “good faith.”

Avenatti, who has been representing himself, told jurors during summations that he believed that he was entitled to the money under his contract with Daniels, which said he would be “entitled to a reasonable percentage to be agreed upon” for any book deal.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this was my money,” Avenatti told the jury on Wednesday. “This was the firm’s money. This wasn’t Ms. Daniels’s money.”

Stormy Daniels via ABC screengrab

Under their instructions, the jury must acquit Avenatti if they find that he believed he acted in “good faith,” even if he was wrong.

“Because an essential element of wire fraud is the intent to defraud, it follows that good faith on the part of a defendant is a complete defense to the charge of wire fraud,” the instructions state. “That is, if the defendant in good faith believed that he was entitled to take the money or property from the victim, even if that belief was mistaken, then you must find him not guilty even if others were injured by the defendant’s conduct. The defendant has no burden to establish good faith. The burden is on the Government to prove fraudulent intent and the consequent lack of good faith beyond a reasonable doubt.”

There was no evidence that Avenatti and Daniels entered into any subsequent agreement over the book deal, and text messages did not show him ever referring to one. The texts only showed Avenatti claiming his client’s book advance never had been sent, after bank records showed that he received and spent the money, according to prosecutors.

(Drew Angerer/Getty Images)