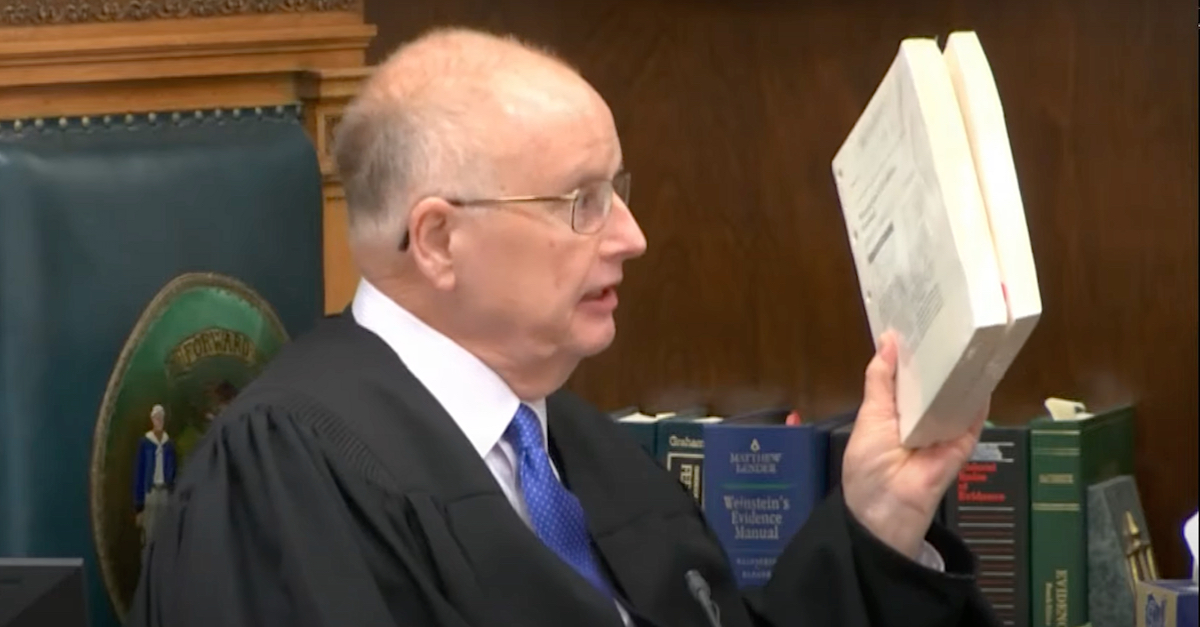

Judge Bruce E. Schroeder. (Image © Mark Hertzberg/ZUMA Press Wire/Pool)

The judge overseeing the intentional homicide trial of Kyle Rittenhouse led the jury on a sojourn into Biblical history while talking about about the roots of hearsay law in the State of Wisconsin.

The issue arose when lead prosecutor Thomas Binger played a video that contained an audio track. In the recording, a narrator from The Rundown Live indicated that he was present at the time of the recording with “a bunch of militia” in Wisconsin and described the vandalism of a car dealership the previous day. Defense attorney Mark Richards said the track contained “editorialization” and should neither have been played nor continue to be played before the jury.

Binger said both parties had consented to the authenticity of the recording. He said the person who made the recording could easily be subpoenaed for confrontation purposes — which is what concerned Judge Bruce Schroeder.

Without mounting much of an argument under the rules of evidence, Binger said he would simply play the recording and turn up the volume when Rittenhouse himself spoke. (The words of a defendant are admissible at trial even if a defendant does not testify.)

Prosecutor Thomas Binger and defense attorney Mark Richards argue over an audio track embedded within an evidence video. (Image via the Law&Crime Network.)

Schroeder seemed satisfied with the proffered resolution but proceeded to lead the jury through a historical retelling of the genesis of modern evidence rules. The jury was present for the entire discussion about the recording despite Binger’s multiple requests to approach the bench or handle the discussion in another manner.

The judge told the jury that said he studied evidence “last century” and sought a prop of printed materials to describe the thickness of his evidence law book from law school. He said the big-picture lesson was that the hearsay rule was the most “murky” portion of the rules of evidence. As if teaching a law school course, he went on to explain why.

(Image via the Law&Crime Network.)

The judge correctly stated that the hearsay rule contains both “exclusions” and “exceptions.” He then discussed why the rules say what they do.

“So, some things that may seem to the untrained ear to be hearsay are not, and some things that don’t seem like it, are,” he said.

Hearsay, the judge summarized, is a rule which says that a “statement of a non-testifying person cannot be offered to prove the truth of the matter which is asserted in the statement.” In other words, a statement “introduced into evidence has to be under oath, it has to be subject to cross-examination, and that’s not true of statements that are made by somebody who is not here while testifying as a witness.”

“So, this person who’s describing this,” Schroeder said of the person in the video, is not subject to the rules of the court; therefore the statements cannot be used as evidence.

Schroeder was taking the long way around to admonishing the jury that it should not rely on the brief statements it heard in the video.

Then came the Biblical monologue:

This is actually referred to in the Bible. Saint Paul, when he was put on trial . . . in . . . I think it’s Caesarea — well, it was over in Palestine — uh, in Israel — he was . . . accused of some activity. And he was a Roman citizen, which is not common, but he happened to have been a Roman citizen. So, he had rights that we share now as Americans. Uh, and — he — when they tried to put him on trial with evidence from — which was being repeated by somebody who wasn’t there and under oath — he said, “where are the witnesses against me? I am a Roman, and I have a right to confront my accusers. They should be here.” And so that led to, actually, his voyage to Rome to have his case heard before the Emperor. Um, so it’s an ancient rule; it’s strictly, strictly enforced in the criminal courts for very obvious reasons.

Um, and, um, s0 — that’s what we’re talking about here. And, um — so — if the person who is making this descriptive material is here and can be put under oath and can be cross examined, uh, then it’s admissible, but otherwise it is not admissible through the officer here.

Schroeder was referring to a detective who was on the stand who introduced the video.

He then went on to explain the exception to the hearsay rule which allowed the statements of Rittenhouse to come into the trial.

Defense attorney Corey Chirafisi, Kyle Rittenhouse, and defense attorney Natalie Wisco discuss a matter in court. (Image via the Law&Crime Network.)

Schroeder didn’t mention it, but the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination also has semi-religious roots. The actions of individuals (e.g., their crimes) were historically governed by government or civil authorities (kings, emperors, governors, and judges); however, the inner workings of a person’s soul were the realm of religious authorities in days of antiquity. That’s why defendants cannot be required to unburden their souls (or, in other words, testify against themselves) before a modern criminal tribunal.

Binger resumed playing the recording, but not without additional objections from Richards.

Watch the exchange below: