Joseph Ray Daniels stands with counsel shortly before opening statements.

Joe Clyde Daniels loved apples.

“That sounds weird right now, but you’ll understand as the trial goes along,” said Ray Crouch, the prosecutor trying to convince a Tennessee jury that the 5-year-old boy was murdered by his own father.

Crouch on Thursday presented opening statements in the trial of Joseph Ray Daniels, who is charged with five counts in connection with Joe Clyde’s death: first-degree murder; first-degree murder during the commission of an underlying felony of aggravated child abuse; aggravated child abuse; initiating a false report; and tampering with evidence.

The prosecutor told assembled jurors that Joe Clyde died on April 4, 2018, but that his aunt captured video of him getting off a school bus the day before with his older brother.

“That’s the last time we have evidence of him being alive on photograph or video,” Crouch said.

“Baby Joe” was 5-years-old when he went missing in TN.

His father admitted killing Joe Clyde Daniels, who was non-verbal autistic. Soon after, the defendant recanted his confession.

The child was last seen on April 3, 2018. Baby Joe has not been found. Watch @LawCrimeNetwork pic.twitter.com/4S9qRJXNTO

— Syma Chowdhry (@SymaChowdhry) June 3, 2021

He described Joe Clyde as an “active young boy” who “loved going to school,” “loved his cowboy boots,” and “loved his plaid, button-up shirts.” The victim also loved “playing with friends” and “one-on-one interaction with teachers.”

Joe Clyde was autistic. He didn’t like loud noises, like thunder, or chaos. Other terms prosecutors used to describe the victim included “global developmental disability.” They said he struggled with gross and fine motor skills, had weak hand muscles, and struggled to separate and isolate his fingers — which made it difficult for him to open items, pick up pegs, open and close zippers, tie his shoes, and button his shirts. He communicated by eye contact, pointing, and through other gestures, prosecutors said, but they described Joe Clyde as “not difficult,” “not frustrating,” and as a child who did not display “negative behaviors.”

Prosecutor Ray Crouch

Father and son — now defendant and alleged murder victim — lived together in a house with eight people. The family was rank with unemployment and with infidelity between the defendant and his wife, Crouch said. The defendant’s wife was planning to leave him. The defendant denied Joe Clyde was his son and searched for information online about paternity tests. He even referred to Joe Clyde as “that boy,” Crouch said. And he allegedly had a temper.

When Joe Clyde died, Joseph Ray Daniels initially claimed that he put his son back to bed, retired himself, and awoke at 5:00 a.m. to find the boy missing. He claimed he searched and found nothing. He then called 911 at 6:22 a.m.

The defendant told first responders that his son must have gone into the living room, moved a coffee table to the door, located a key, unlocked a padlock, returned the key, hid the padlock among his toys, returned the table to its usual position, and took off in the middle of a thunderstorm.

Prosecutors said the entire chain of events made no sense whatsoever given Joe Clyde’s physical and mental condition.

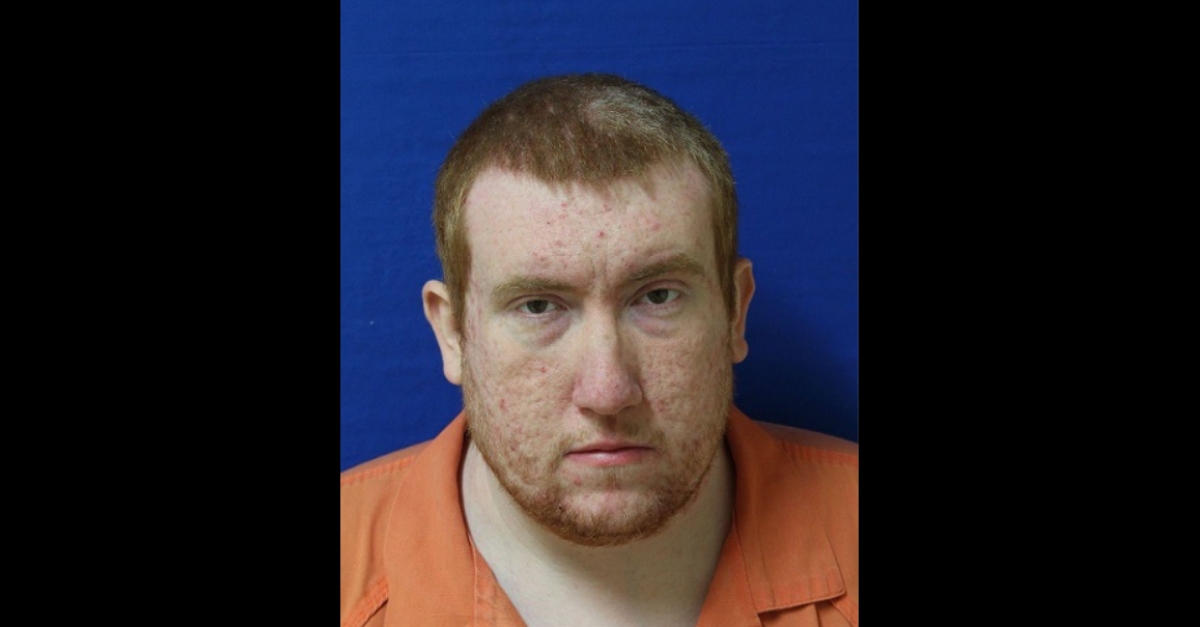

Joseph Ray Daniels is seen in a Tennessee Bureau of Investigation mugshot.

A massive search involving humans, canines, divers, infrared cameras, airplanes, and highway patrol officers. Various ponds were drained completely. Volunteers assisted.

Prosecutors said the defendant confessed two and a half days later by driving with his wife to the police department and giving himself up, in essence, to law enforcement. He said he moved the coffee table himself, handled the lock himself, and that the entire story was made up from day one.

The defendant then confessed on video to whipping Joe Clyde for urinating on the floor, Crouch told the jury. When the boy laughed, the defendant said he whipped him again, according to the state. Then the defendant put his son outside. When the boy ran toward the road, the defendant brought him back inside and “slam[med] his body” on a coffee table, according to the prosecutor’s re-telling of the defendant’s alleged account.

Through it all, the defendant was “angry,” Crouch said.

The defense objected on grounds that the state had not yet submitted the confession into evidence and had not proven that the confession was voluntary and trustworthy through independent corroborating evidence. Prosecutors countered that opening statements were not evidence and that the defense had already raised questions during jury voir dire about whether false confessions were possible.

The judge allowed the state to proceed after settling the objection in favor of the prosecution and allowing the defendant to take medication.

After the brief interlude, which could not have been timed better for dramatic effect, Crouch reminded the jury that the defendant admitted to killing his son.

“He admits to police that he killed Joe Clyde,” Crouch said. “The defendant also says, ‘when I get angry, things happen.’ And we’re going to prove to you that night that he did get angry and things did happen: the murder of Joe Clyde Daniels. The defendant specifically tells investigators that he did not stop hitting Joe Clyde until he realized he had lost control.”

The defendant admitted his 8-year-old “saw everything,” Crouch said, and that the defendant threatened to kill that child if he talked.

Joseph Ray Daniels said he washed the clothes he was wearing and eventually led the authorities to the location where he had “concealed” his son’s body.

But that was a lie, Crouch said.

“The defendant never intended to disclose the location or what exactly he did to Joe Clyde’s body,” the prosecutor then said.

The defendant then demanded money for his son’s funeral before he would reveal where he hid his son’s body. The child’s body has never been found, Crouch said, despite the defendant providing yet another description of what allegedly happened to the remains.

The defendant said later on he threw Joe Clyde’s body into the trunk of his car, drove to a truck stop nine miles away, made a purchase, and then threw the dead boy’s body into the water from a bridge. Law enforcement took the defendant to “multiple bridges,” Crouch said, but the defendant never led them to his son.

A written confession was obtained. He even told his own father he “beat Joe Clyde” after telling the authorities multiple stories.

Crouch, anticipating an attack from the defense, spent time explaining to the jury that the state’s position is that none of the defendant’s several confessions were coerced.

Defense attorney Jake Lockert said testimony would reveal that Joseph Ray Daniels went about his morning routine the day his son disappeared and was the person who alerted the authorities that something was amiss.

Jake Lockert

Lockert said the police constantly accused the defendant of lying and that the defendant repeated 20 times over again that he didn’t do anything wrong over a period of hours. The defense said the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation fed the defendant details which the defendant then regurgitated to placate his interrogators.

The defense tactic is common in many trials involving police interrogations.

“Keep in mind: my client’s mentally ill,” Lockert said. “At first he thinks he’s in trouble because they forgot to lock the door.”

That’s why Lockert said Joseph Ray Daniels blamed the victim for the escape.

“They stayed on him,” Lockert said. “They wanted something more.”

And so the story changed, the defense said.

Agents told Joseph Ray Daniels they “would have whooped [the victim’s] ass, too” for urinating on the floor.

“Say you’s mad, say you whipped his ass, say you beat him,” Lockert said the interrogators prodded his client.

So his client “goes a little further and says, ‘okay, yeah, I, I whipped him hard.'”

Lockert said an agent was the one who suggested how many times the victim was whipped, and the defendant agreed.

“He just gradually adopts what they’re telling him,” Lockert said. At one point, the interrogators told the defendant he could “walk out the door” if he agreed with their version of the story. And so the client believed them.

“I submit to you it was a false confession,” Lockert said.

He added that forensic evidence of a beating was severely lacking. He added that a witness reported seeing a “teenager” or “smaller person” fitting Joe Clyde’s description and wearing Joe Clyde’s last known clothing was seen sitting on the side of the road a third of a mile away from home after the defendant allegedly confessed the boy was dead.

If the witness is telling the truth, then the confession is a lie, Lockert said.

He noted that his client was a “grown adult” who weighs 282 pounds and could not be confused for a “smaller person.”

“That’s the tight proof in this case that will give you reasonable doubt,” he continued.

Another neighbor reported that her child’s boots disappeared off a front porch when Joe Clyde was possibly missing. And another neighbor claimed to have seen a boy wearing dirty pajamas. No through searches resulted from those tips, Lockert said.

“You’re gonna hear that they took a mentally ill person and essentially tricked him into making up a confession that they figured out pretty quickly was not true,” Lockert said in summary while pointing to inconsistent video evidence from the scene and a lack of blood at the scene where a child was allegedly beaten for 15 minutes. “They gonna ask you to believe that if you kill a child, you gonna call the police out there when you still have the body in the trunk of your car. That’s the most absurd thing I’ve ever heard. They don’t have a case. They keep changing the facts to get to it, and that’s what you’re gonna see in this case.”

[courtroom images via the Law&Crime Network; defendant’s mugshot via the TBI; images of victim via courtroom evidence photos]