Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison

Attorneys for at least two of the four former police officers accused of playing a role in the alleged murder of George Floyd on Tuesday asked that Minnesota’s highest law enforcement officer be held in contempt of court and sanctioned by a judge.

“Defendant, by and through counsel, respectfully moves the Court for an order holding Keith Ellison, the Attorney General for Minnesota and lead prosecutor in the above-captioned case, in contempt of court and ordering sanctions as a result of his actions,” wrote Robert M. Paule, an attorney for accused ex-cop Tou Thao.

Thao’s attorney says Ellison violated a gag order issued July 9 by District Court Judge Peter A. Cahill.

Thao’s motion does not explicitly say what Ellison said which trigger the request for contempt and sanctions. However, a document filed later Tuesday by attorneys for accused ex-cop Thomas Kiernan Lane explicitly states that Ellison committed an “obvious violation” the gag order by issuing a Monday press release press release announcing a series of additions to his office to assist with the Floyd prosecution.

The press release said “four seasoned attorneys and trial lawyers” were joining his office and were working for free. The team includes Neal Katyal, a former acting U.S. Solicitor General, along with Lola Velázquez-Aguilu, Jerry Blackwell, and Steven L. Schleicher.

“Out of respect for Judge Cahill’s gag order, I will say simply that I’ve put together an exceptional team with experience and expertise across many disciplines,” Ellison said in the press release. “We are united in our responsibility to pursue justice in this case.”

Lane’s attorneys were blunt with their criticism. They cut into Ellison and the AG’s deputy chief of staff, John Stiles, who disseminated the press release.

“Ellison should be jailed along with Stiles. There is no reason to announce that these so called ‘super stars’ are joining the prosecution and that they’re doing it for free,” Lane’s attorneys told the judge in court papers. “It is an obvious statement to the public that these ‘super stars’ believe that our clients are guilty. Further proof that the news release was done to influence the public is that it was released by John Stiles, who, according to Google, is a chief strategy officer and builds reputations and brands.”

Despite the defense claims, the phrase “super stars” appears nowhere in the press release. The additions to Ellison’s office are described as an “exceptional team” and as “seasoned attorneys.”

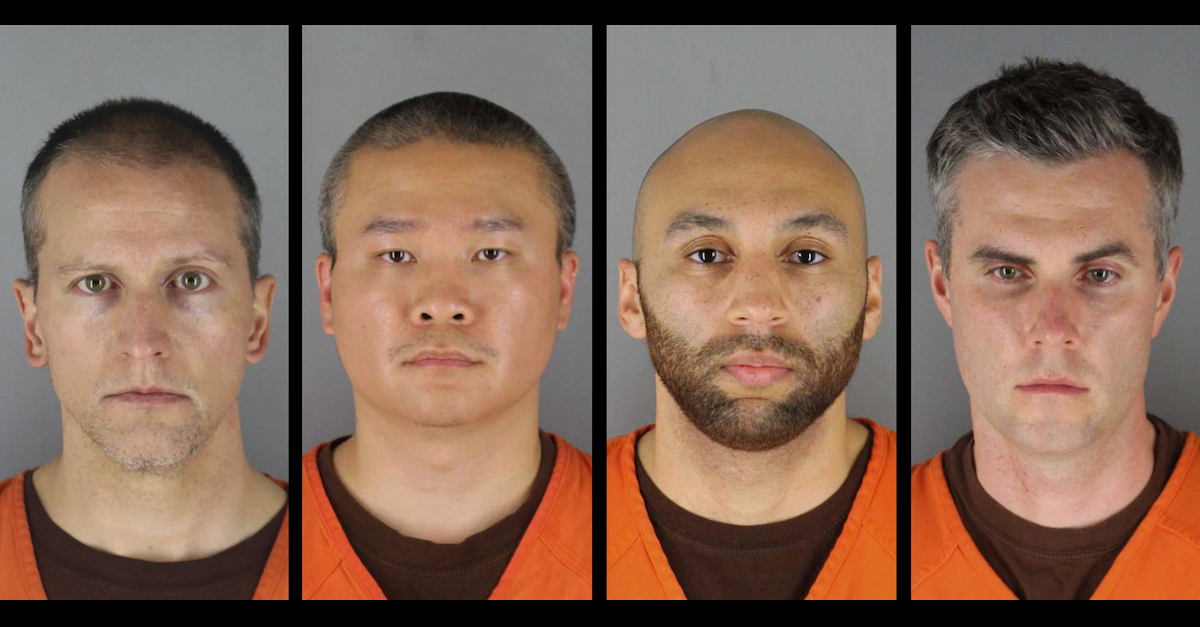

Derek Chauvin, Tou Thao, J Alexander Kueng, and Thomas Kiernan Lane

Here is the background which led to Tuesday’s flurry of court filings.

The judge’s July 9 gag order applied to all attorneys and their representatives associated with all four cases, but it appeared to be aimed mostly at the defense attorneys — specially those representing co-defendant Thomas Kiernan Lane.

“The Court has been made aware that two or more attorneys representing parties in the [George Floyd] cases granted interviews or talked with the media yesterday, expounding on the merits of the case or commenting on other aspects of the case after a motion to dismiss was filed,” the July 9 gag order reads. “The court finds that continuing pretrial publicity in this case by the attorneys involved will increase the risk of tainting a potential jury pool and will impair all parties’ right to a fair trial.”

Lane’s attorneys defended what they said publicly in a subsequent court document.

“Nothing defense counsel filed or said warrants this Court to issue a Gag Order,” they said. “The memorandum filed was supported by exhibits provided to us by the State. Defense counsel, because the videos were not public at the time of the interviews, attempted to explain the dismissal motion and the exhibits as it was grossly unfair to hold back the videos and only allow the reading of the transcripts of the videos. Indeed any statement this defense counsel made could barely remedy the prejudicial publicity cited in [a separate] memorandum.”

Defense attorneys for the other defendants also objected to the gag order.

Attorneys for J. Alexander Kueng said they did not comment to the press about on body camera videos filed as exhibits — but said the court’s lack of diligence in making the videos and other documents available to the public was causing its own sort of prejudice against the defendants:

While all matters were filed publicly; none of those pleadings were made available to the public for approximately 24 hours after filing. Exhibits 3 and 5 (the videos) remain hidden from the public and media by Court’s personnel who liaison with media.

Shortly after a portion of those filings were made public media outlets began vigorously reporting on their content. The reporting was incomplete and tainted because the Court denied access to the videos to the public. On July 8, 2020 Counsel was contacted by several media outlets and informed that court personnel were refusing to allow access because this Court was not available to provide guidance to staff on how to release the videos. Counsel was contacted by roughly a dozen media outlets seeking comment on the videos and motions and declined to comment.

Attorneys for Tou Thao referenced an earlier June 29 admonition from a judge not to discuss the case in arguing against the July 9 gag order. They also ragged on government officials and those connected to the victim’s family as the reason for the original admonition not to talk publicly about the case:

The fact that attorneys in other related cases (as no joinder motions are properly before this court) spoke publicly regarding their case(s) has not threatened to prejudice Mr. Thao’s constitutional right to a fair and public trial. In fact, the very reason behind the Court’s admonition was the fact that numerous public figures (Governor Walz, Mayor Frey, Mayor Carter, BCA Chief Harrington, Minneapolis Police Chief Arradondo, and civil attorney Benjamin Crump) and both prosecuting attorneys (Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman and Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison) made repeated public statements that were highly prejudicial and referred to inadmissible evidence regarding the case. The Court must weigh all “all reasonable alternatives” to a gag order at this point in this case including a change of venue. A gag order is not the correct prescriptive measure until the Court rules on whether a change of venue is appropriate in this case.

Attorneys for Derek Chauvin argued against the gag order by saying they had not spoken about the case but that the court was nonetheless wrong to issue it.

The Court issued its order sua sponte, without sufficient notice to Defendant, without citing legal authority, and without a hearing. Defendant objects to the Court’s Gag Order and requests that it be vacated.

[ . . . ]

We have not yet reached the omnibus hearing in this case, yet Mr. Chauvin has frequently been called a “murderer” or “killer” in the press, and the death of George Floyd has been referred to as a “murder” in global media and across news headlines countless times. Since the week of the incident, Attorney General Keith Ellison, who was charged with prosecuting this case, has appeared in the local and national press, making statements like, “Nor would I be part of a prosecution unless I believed the person was guilty and… needed to be held accountable” and “This case is unusual because of the way Mr. Floyd was killed and who did it: at the hands of the defendant, who was a Minneapolis Police officer.”

The Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct, like those of most (if not all) other states, generally prohibit attorneys from speaking publicly about their cases. However, in Minnesota, like most other states, exceptions apply. Lawyers in Minnesota are allowed to make public statements “that a reasonable lawyer would believe is required to protect a client from the substantial undue prejudicial effect of recent publicity not initiated by the lawyer or the lawyer’s client.”

“A statement made pursuant to this paragraph shall be limited to such information as is necessary to mitigate the recent adverse publicity,” the rules further state.

Minnesota notably does not contain an explicit exception which allows attorney to discuss matters already part of the the public record. Such explicit exceptions are contained in model rules promulgated by the American Bar Association and are codified by the rules of many states.

[photo by Scott Heins/Getty Images]