Ethan Robert Crumbley, 15, appears in a mugshot released by the Oakland County Jail in Michigan.

Accused Michigan high school shooter Ethan Crumbley plans to assert an insanity defense to charges he gunned down four classmates and injured seven others. That’s according to court papers filed Thursday in Oakland County’s Sixth Circuit Court and which were subsequently obtained by Law&Crime.

Crumbley, 15, is charged with four counts of first-degree premeditated murder, seven counts of assault, and 12 weapons offenses in connection with a deadly attack that left Hana St. Juliana, 14, Tate Myre, 16, Madisyn Baldwin, 17, and Justin Shilling, 17, dead. Crumbley is also charged with terrorism.

The terse Thursday court filing says Crumbley “intends to assert the defense of insanity at the time of the alleged offense and gives notice of his intention to claim such a defense.” It is signed by his attorneys Paulette Loftin and Amy Hopp.

Legal insanity is synonymous but distinct and separate from the psychological or mental health use of the term. In Michigan, which follows the Model Penal Code’s version of the insanity defense, insanity is an affirmative defense. A state statute explains what insanity means for a criminal defendant:

An individual is legally insane if, as a result of mental illness as defined in section 400 of the mental health code . . . or as a result of having an intellectual disability as defined in section 100b of the mental health code . . . that person lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his or her conduct or to conform his or her conduct to the requirements of the law. Mental illness or having an intellectual disability does not otherwise constitute a defense of legal insanity.

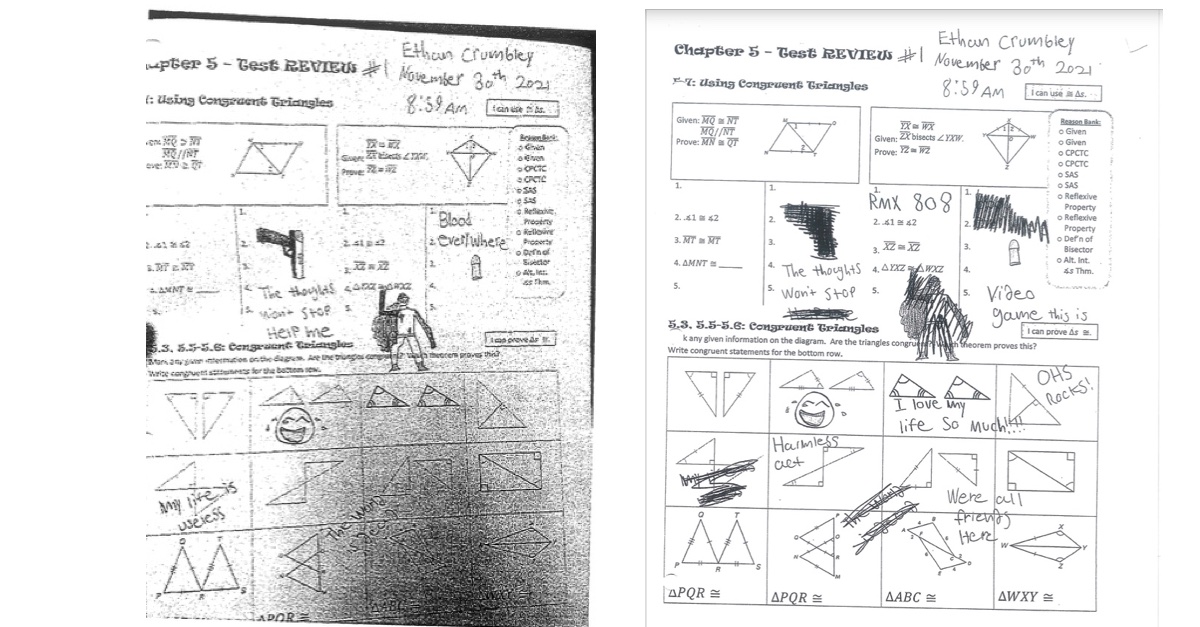

Under Michigan law, Crumbley “has the burden of proving the defense of insanity by a preponderance of the evidence.” But prosecutors will surely attack Crumbley’s attempts by pointing to the defendant’s suspiciously guilty-looking behavior. In this case, to show that Crumbley knew the “wrongfulness of his . . . conduct,” prosecutors will likely point to the defendant’s alleged decision to scratch out violent images he drew on a school worksheet. The defendant’s attempt to obscure the images is some evidence, prosecutors are likely to suggest, that Crumbley knew that shooting and killing people was wrong. His act of crossing out the images suggests that he knew he had to “conform his conduct to the requirements of the law,” prosecutors are also likely to point out.

Court records contain copies of images allegedly drawn by Ethan Crumbley before he is accused of shooting and killing four people at Oxford High School. The image on the left portrays a photo of the original drawings taken by a school employee; the image on the right depicts how they were allegedly modified by Crumbley after a teacher caught him and commenced a disciplinary process.

Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald has already predicted that any asserted insanity defense would likely fall flat for Crumbley, the Detroit Free Press reported.

The initial Thursday defense filing claims to have been made “pursuant to” Mich. Comp. Laws § 769.20a, but that statute has been repealed since June 1972. Crumbley’s defense attorneys told Law&Crime they almost immediately filed a correction to cite § 768.20a, which is the law that requires notice in insanity cases. Per the correct and current statute:

(1) If a defendant in a felony case proposes to offer in his or her defense testimony to establish his or her insanity at the time of an alleged offense, the defendant shall file and serve upon the court and the prosecuting attorney a notice in writing of his or her intention to assert the defense of insanity not less than 30 days before the date set for the trial of the case, or at such other time as the court directs.

Said notice was summarily tendered via the Thursday court filing.

The statute then requires the court to “order the defendant to undergo an examination relating to his or her claim of insanity by personnel of the center for forensic psychiatry or by other qualified personnel, as applicable, for a period not to exceed 60 days from the date of the order.” Any personnel who commence the mandatory evaluation “may perform the examination in the jail, or may notify the sheriff to transport the defendant to the center or facility used by the qualified personnel for the examination, and the sheriff shall return the defendant to the jail upon completion of the examination.”

The status of Crumbley’s incarceration — he’s being held in an adult facility at the request of prosecutors and against the requests of his defense attorneys — could therefore change pursuant to the defense motion.

The statute goes on to say that Crumbley can “secure an independent psychiatric evaluation by a clinician of his . . . choice on the issue of his . . . insanity.” The statute says the state promises to pay for that independent review if Crumbley is declared indigent.

Other sections of the law require Crumbley to “fully cooperate” with mental health examiners — since he’s the one asserting the defense. A failure to cooperate would bar Crumbley from eliciting evidence at trial to support the defense. Any statements Crumbley makes to his examiners would not be considered admissible evidence, the law points out, “on any issues other than his or her mental illness or insanity at the time of the alleged offense.”

The statute requires Crumbley’s examiners to author a written report of their clinical findings and the facts upon which those findings are based. Prosecutors are allowed to rebut the findings.

Yet another law explains how the case may theoretically conclude if the case proceeds to trial. Crumbley may be found “guilty but mentally ill” if a trier of fact (a jury or a judge) finds all of the following:

(a) The defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of an offense.

(b) The defendant has proven by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she was mentally ill at the time of the commission of that offense.

(c) The defendant has not established by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she lacked the substantial capacity either to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his or her conduct or to conform his or her conduct to the requirements of the law.

If the case doesn’t go to trial but ends with a plea of some form, a different procedure takes place:

[T]he trial judge, with the approval of the prosecuting attorney, may accept a plea of guilty but mentally ill in lieu of a plea of guilty or a plea of nolo contendere. The judge shall not accept a plea of guilty but mentally ill until, with the defendant’s consent, the judge has examined the report or reports prepared in compliance with section 20a of this chapter, the judge has held a hearing on the issue of the defendant’s mental illness at which either party may present evidence, and the judge is satisfied that the defendant has proven by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant was mentally ill at the time of the offense to which the plea is entered. The reports shall be made a part of the record of the case.

“If a defendant is found guilty but mentally ill or enters a plea to that effect which is accepted by the court,” the statute continues, “the court shall impose any sentence that could be imposed by law upon a defendant who is convicted of the same offense.”

In other words, the length of a potential sentence might not necessarily change because of the invocation of an insanity defense, but the treatment of an incarcerated defendant does change:

If the defendant is committed to the custody of the department of corrections, the defendant shall undergo further evaluation and be given such treatment as is psychiatrically indicated for his or her mental illness or intellectual disability. Treatment may be provided by the department of corrections or by the department of community health as provided by law.

[ . . . ]

When a treating facility designated by either the department of corrections or the department of community health discharges the defendant before the expiration of the defendant’s sentence, that treating facility shall transmit to the parole board a report on the condition of the defendant that contains the clinical facts, the diagnosis, the course of treatment, the prognosis for the remission of symptoms, the potential for recidivism, the danger of the defendant to himself or herself or to the public, and recommendations for future treatment. If the parole board considers the defendant for parole, the board shall consult with the treating facility at which the defendant is being treated or from which the defendant has been discharged and a comparable report on the condition of the defendant shall be filed with the board. If the defendant is placed on parole, the defendant’s treatment shall, upon recommendation of the treating facility, be made a condition of parole. Failure to continue treatment except by agreement with the designated facility and parole board is grounds for revocation of parole.

Read the defense filing below: