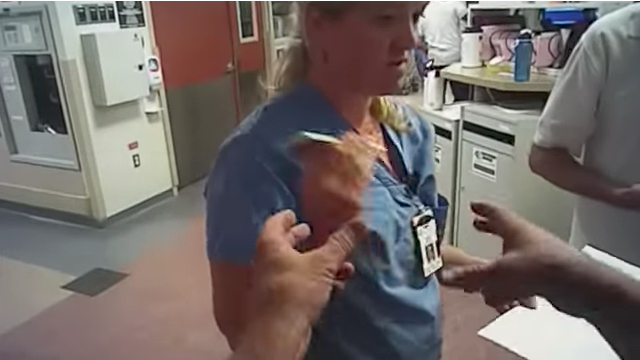

Reaction to the treatment of Alex Wubbels at the hands of Salt Lake City Detective Jeff Payne has resulted in the unthinkable: a brief moment of national unity.

Payne’s use of force and arrest of Wubbels–her terrified screams echoing against the refusal to give into a bullying authoritarian–have catapulted the video beyond viral fame into a collective moral indictment and how-to guide for modern heroics. A police officer was caught abusing a citizen and, as of now, there have been no apologetics issued to polish his boots or explain why the victim had it coming. Finally, Americans have found a cause of police brutality to revile as one.

Still, there’s always the potential of Fox and Friends learning about what happened. So just in case you’re forced to discuss that nurse in Utah or the political economy of blood draws with older relatives this Labor Day weekend, here’s why anyone sticking up for Detective Payne is completely wrong as a matter of law.

Hospital Policy

First, we consider the hospital policy and Wubbels’ obligations as a nurse operating under the auspices of that policy.

As she very patiently explained to Payne prior to her unwarranted–and likely unlawful–arrest, there are only three circumstances where blood draws are allowed from patients believed to be under the influence: (1) with a warrant; (2) with patient consent; or (3) if the patient is under arrest.

None of those criteria were satisfied. Payne did not have a warrant and told Wubbels this repeatedly.

Further, if not obviously, the patient in question could not consent that night in Utah, because he was not conscious. And he was not under arrest or apparently even facing the prospect of arrest. (Even if the patient had been under arrest, a warrantless blood test without a valid warrant would be a violation of the Fourth Amendment.)

As for any lingering confusion as to Wubbels’ responsibilities and interpretation of hospital policy, it should be noted that the University of Utah Hospital is standing by their nurse. In a statement issued September 1, the nursing department and hospital administration wrote:

During a stressful situation Nurse Wubbels chose to focus first and foremost on the care and well-being of her patient. She followed hospital procedures and protocols in this matter and was acting in her patient’s best interest.

Finally, it should be noted that the hospital’s policy was agreed upon mutually between the hospital and local police. Detective Payne either was aware of the policy or should have been aware of the policy and all exceptions. Ignorance of the rules is no excuse to flout them–especially for a cop.

Implied Consent

Second, let’s consider the concept of “implied consent”.

According to a report filed by Lt. James Tracy following Wubbels’ arrest, Payne was advised to arrest the nurse because she was interfering with a police investigation and Payne had the authority to draw the blood sample from the injured man due to Utah’s “implied consent” law. Tracy was completely in the wrong as a matter of law here because “implied consent” to draw blood was struck down by the Utah Supreme Court over 10 years ago.

In State v. Rodriguez, the court wrote:

[I]t is difficult for us to imagine that the United States Supreme Court could muster the assurance that the consequences of alcohol dissipation are so great and the prospects for prompt warrant acquisition so remote that per se exigent circumstance status be awarded to seizures of blood for the purpose of gathering blood-alcohol evidence. Accordingly, we decline to grant per se exigent circumstance status to warrantless seizures of blood evidence.

The immediately above block of text is using slightly different language, but essentially states that blood draws are not granted an exception to the warrant requirement just because the state legislature (and police) think they should be. Tracy and Payne should have been well aware of the change in law seeing as how it occurred more than a decade prior.

The Fourth Amendment

Finally, let’s briefly consider the basic necessity of a warrant here.

Recall that Detective Payne did not have a warrant and could not get a warrant because there was–admittedly–no probable cause. Probable cause is a necessary component for a valid search and seizure warrant. And a search and seizure warrant is a constitutional requirement for the court room admissibility of blood removed from someone without their consent. In other words, cops cannot draw blood without a warrant and there was no warrant here.

This is the major holding in Birchfield v. North Dakota.

That case was decided just last year, however, it is incumbent on police officers, detectives and lieutenants to be well-versed in the constitutional rules governing their occupations. Nurse Wubbels was aware of the law on point. The police have absolutely no excuse.

[image via screengrab]