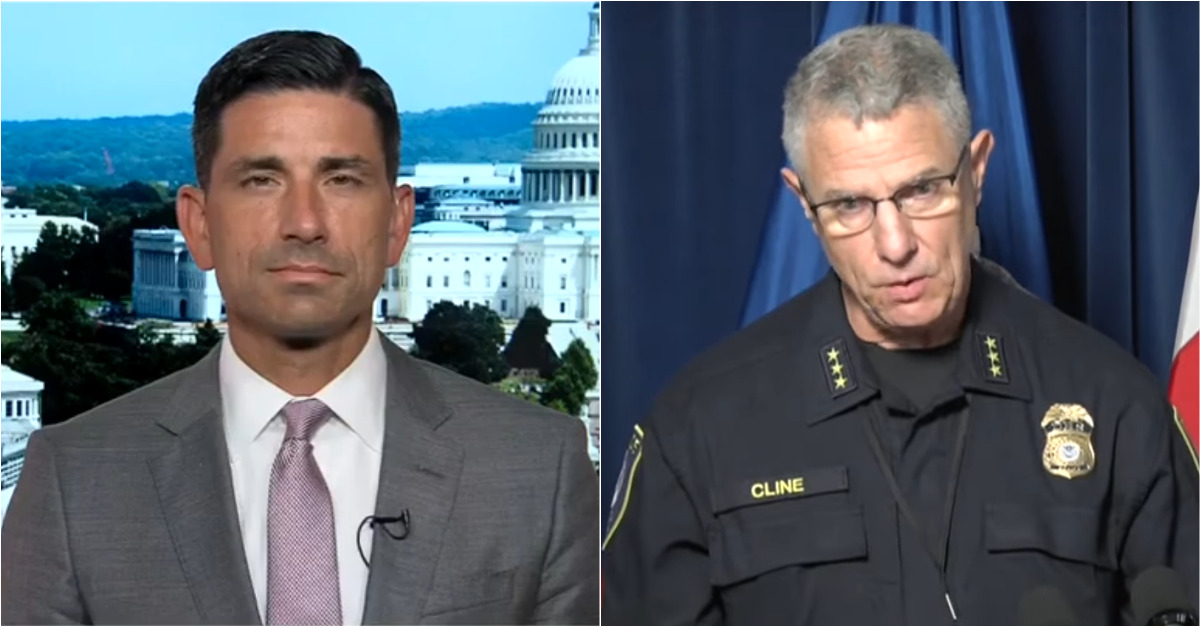

Acting Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Chad Wolf and one of his subordinates appear to have admitted their agents have been making unconstitutional arrests of Black Lives Matter protesters in Portland during a series of public appearances.

Here’s the exact comment.

“Anytime that you attack a federal facility such as a courthouse in Portland that is a federal crime,” Wolf told Fox News host Martha MacCallum on Tuesday night. “Attacking federal police officers–law enforcement officers–which they have done for 52 nights in a row is a federal crime. So, the Department, because we don’t have that local support, that local law enforcement support, we are having to go out and proactively arrest individuals and we need to do that because we need to hold them accountable.”

Anticipatory arrests, of course, are prohibited under the U.S. Constitution.

Those Fox News comments tracked with an explanation given by Deputy Director of the Federal Protective Service Richard Kris Cline–who was asked to field a question originally addressed to Wolf about infamous and widely-criticized footage of DHS agents silently abducting protesters and forcing them into unmarked vehicles.

“What level of probable cause are you getting?” a reporter asked on Tuesday during a press briefing. “Because some people are saying that they’re being detained on the sidewalk by an agent they don’t recognize and being put into an unmarked vehicle. So, what exactly, is the standard of probable cause you are getting and how is that not a violation of civil liberties?”

Wolf noted that his agents were not going directly into crowds of protesters because Portland is currently “a very difficult environment to work in.” He also said that his agents were using probable cause, but declined to elaborate, before turning the microphone over.

“So, in this instance, you’re probably talking about the van,” Cline said. “So the CBP, the Border Patrol officers–that have been cross-designated with our authority–the individual that they were questioning was in a crowd and in an area where an individual was aiming a laser at the eyes of officers.”

That explanation immediately set off alarm bells from legal experts.

Harvard Law Professor Andrew Crespo summed up the constitutional issues with the Kline-Wolf approach.

“I don’t know if shining a laser at someone is a federal crime,” he wrote. “It doesn’t matter. The police do not have probable cause to arrest you just because you are standing near someone else who may have committed a crime.”

The U.S. Supreme Court, Crespo noted, weighed in on this issue in a landmark Fourth Amendment case from 1979.

In Ybarra v. Illinois, a 6-3 majority of justices concluded that a state statute allowing police to search people on the premises of a location where a valid search warrant is executed violates both the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unlawful searches and seizures as well as the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of Due Process.

Per that still-undisturbed decision:

[A] person’s mere propinquity to others independently suspected of criminal activity does not, without more, give rise to probable cause to search that person. Where the standard is probable cause, a search or seizure of a person must be supported by probable cause particularized with respect to that person.

The Harvard Law professor explained that this standard is actually well-known in the common parlance as well: the law–and an ethical worldview–does not and cannot support the notion of “guilty by association.”

“We have people in the area that observe–keep track of him–where he’s going,” Cline noted. “We don’t want to go into the crowd because then it’s a fight between our guys and the demonstrators, so we wait until the individual gets into a somewhat quiet area where we don’t expect violence to talk to him.”

According to Cline, however, other protesters appeared and the DHS troops decided to take the person of interest . Cline said they asked the protester to leave. The video appears to show that the protester was detained by two troops using force.

“They did take them to an area that was safe for both the officers and the individual to do the questioning,” he said. “It’s not a custodial arrest. We need to question this individual to find out what their role was in this laser-pointing.”

Eventually, Cline said, the protester was released “because [DHS] did not have what they needed.”

“Translation: They did not have probable cause,” Crespo stated.

2. This man was arrested.

— Andrew Crespo (@AndrewMCrespo) July 22, 2020

Crespo took issue with Kline’s suggestion that his agents are acting constitutionally because they are not performing custodial arrests.

The nation’s high court also settled the arrest issue–again in 1979.

In Dunaway v. New York the Supreme Court considered whether police violated the Fourth and 14th Amendments when–lacking probable cause–they took a person into custody, transported him to a police station and detained him for interrogation. Once again, six justices found that police violated the U.S. Constitution with such actions.

Per that landmark case:

[T]he detention of petitioner was in important respects indistinguishable from a traditional arrest. Petitioner was not questioned briefly where he was found. Instead, he was taken from a neighbor’s home to a police car, transported to a police station, and placed in an interrogation room.

The Dunaway holding–prohibiting alleged non-custodial arrests–was unanimously reaffirmed by the court in 1984.

Crespo noted: “The person in charge of this newly beefed up, paramilitary federal police force DOES NOT KNOW WHAT AN ARREST IS.”

And if the Deputy Director of this new federal force will say on national TV that what these officers did was legal because “this wasn’t an arrest,” that raises serious concerns about what his officers are doing out on the street. When the cameras are on, and when they’re not.

— Andrew Crespo (@AndrewMCrespo) July 22, 2020

[images via screengrab/Fox News/Department of Homeland Security]