House Democrats introduced an article of impeachment against President Donald Trump on Monday for incitement of insurrection. Like any good villain-versus-America sequel, the latest impeachment promises to be more dramatic than the first. There is even a through-line connecting the motive, a grave abuse of power to cheat in an election. The voice-over practically writes itself: This time, the crimes are higher; the stakes are bigger, and two new Democratic Senators from Georgia are scheduled to be sworn in just in time.

Impeachment 2.0 promises faster and clearer drama, along with some key differences from its predecessor. Not only is the current effort to remove the president coming in the final days of his presidency and after an armed insurrection at the Capitol, but there are also key procedural differences that are likely to affect the outcome.

1. The votes for a second impeachment are far more likely to convict Trump

For Trump’s first impeachment in the House and trial in the Senate, there were few surprises with respect to votes. Now, the votes have changed a bit. Let’s do some side-by-side.

House votes then:

The House voted for the charge of abuse of power: 230 in favor, 197 against, and 1 abstention (Tulsi Gabbard); the vote fell along party lines, with all House Dems and Independent Justin Amash voting for the articles except Collin Peterson and Jeff Van Drew (Van Drew later switched parties to become a Republican). The votes on a second offense (obstruction of Congress) were the same, save that an additional Democrat (Jared Golden) voted against the charge. Three representatives did not vote: Republican Duncan D. Hunter (he was was banned from voting under the House’s rules after pleading guilty to illegal use of campaign funds, and has now been pardoned by President Trump); Democrat José E. Serrano, (for health reasons); and Republican John Shimkus (who was traveling internationally).

House votes now:

The 117th Congress has 222 House Democrats, 211 Republicans, and 2 vacancies.

Assuming that all or most Democrats vote in favor of Articles of Impeachment, the necessary majority vote will be easy to attain. The simple majority required is expected to vote in favor of impeachment.

Here is the article of impeachment I just introduced, along with 213 colleagues, against President Trump for Incitement of Insurrection.

Most important of all, I can report that we now have the votes to impeach. pic.twitter.com/RaJIjzQSvm

— David Cicilline (@davidcicilline) January 11, 2021

Senate votes then:

After trial, Trump was ultimately acquitted by the Senate on both counts. A conviction required that two-thirds of the Senate (67 Senators) voted to convict. The votes fell along party lines: 52 and 53 Republicans voted not guilty on the abuse of power and obstruction of Congress charges respectively, while all 45 Democrats and 2 Independents voted guilty. Senator Mitt Romney (R-Mass.) was the one Republican to vote to convict Trump for abusing is power, making him the first Senator ever to vote against a member of his own party at an impeachment trial.

Senate votes now:

The Senate, once fully sworn in, will be made up of 50 Republicans, 48 Democrats, and 2 Independents expected to vote with Democrats. Tie-breaking votes are cast by the Vice President. Until January 20, 2021, that tie-breaker will be Republican Mike Pence; thereafter, it will be Kamala Harris, a Democrat.

Georgia Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff won their Senate run-off races in the Peach State just hours before the Capitol riots. Neither Warnock nor Ossoff has been sworn into the Senate yet, as Georgia must first certify its election. January 15 is the Georgia deadline for counties to certify their results, and January 22 is the deadline for state certification. The Senate can swear in both new Senators any time thereafter.

Assuming a trial would take place following Warnock and Ossoff’s swearing-in, this has potential to make Impeachment 2.0 that much more interesting. Several Republicans have already made public statements denouncing Trump’s role in the Capitol riots. To achieve the necessary two-thirds for conviction, the incoming Senate would require 17 Republicans to vote against Trump.

While 17 Republicans voting to convict a member of their own party is far from a certainty, the riots at the Capitol have changed political tides significantly. If ever there were a time when Senators might cross party lines to convict, this could be it.

Republican Senators Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska have already called for Trump’s resignation. Republican Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska has committed that he will “consider” articles of impeachment. Several other prominent Republican officials, including Governors Phil Scott (R-Vt.), Larry Hogan (R-Md)., and Charlie Baker (R-Mass.) have also come out publicly against Trump.

That is less than one week after the siege—and before the presentation of evidence.

2. Rules for Senate Trial

As with Trump’s first trial in the Senate, it is the Senate itself that creates the rules. Unlike a true trial in which a judge enforces standard rules of court, impeachment trial rules are adopted by Senatorial vote. As we discussed during the first trial, the “presiding officer” (which would again be Chief Justice John Roberts) has some power, but is limited by the will of the Senate. Even if Roberts makes a ruling, that ruling can be questioned by any senator – and then overruled by a simple majority vote.

As a political proceeding and not a trial, there is no venue for appeal and no meaningful rulings from the bench. Recall that in non-presidential impeachments, the Vice President of the United States presides over the Senate trial. During a presidential impeachment, the Chief Justice stands in to avoid any conflict of interest.

All this means that the power of the proceedings lies with a simple Senate majority. Procedural rules, objections, and any other disputes during Trump’s second impeachment trial will be decided by a Democratically-controlled Senate.

There are some limited circumstances in which the Chief Justice, as presiding officer, would be the tie-breaker during Trump’s second impeachment trial. Chief Justice Roberts would not be empowered to cast a deciding vote on whether or not to convict Trump; rather, he could only break a tie on the issue of a procedural matter such as admissibility of evidence or testimony of witnesses.

It’s unclear if Roberts would preside if Trump impeachment trial no. 2 were to occur after he is out of office.

3. The penalty on the table for Trump

On top of the what some have described as Trump’s ongoing coup attempt, many have emphasized the danger resumes even after his rapidly expiring term of office, making disqualification necessary.

This was contemplated in the closing line of Trump’s first impeachment.

“President Trump thus warrants impeachment and trial, removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States,” the December 2019 articles of impeachment concluded.

In light of the Capitol insurrection, the need to ensure Trump’s permanent departure from federal office now seems like more than simply a punitive coda, not to mention an effort to remove a possible putschist from the seat of power: it now seems a reasonably critical measure to protect the American government from present and future Trumpism.

It’s important to note that the penalty phase follows the conviction of an impeached president is far simpler than the conviction itself. If convicted, Article II, Section 4 mandates that the president “shall be removed from Office.” The Senate will have no discretion on that account: a conviction means an automatic removal.

If convicted, disqualification is a possible — thought not absolutely necessary — consequence for Trump. Article I, section 3, clause 7 provides that, “judgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States.” This clause both emphasizes the non-criminal nature of the impeachment process, and raises disqualification as a discretionary penalty.

Impeachment expert Ross Garber explained earlier to Law&Crime that there is some disagreement over the functionality of the disqualification provision.

“That clause is limited to precluding an official from holding ‘any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States,’” Garber said. “The text of other provisions of the Constitution suggests this does not include the presidency or a seat in the House or Senate.”

Indeed, legal scholars have often recognized the inconsistency in language within the Constitution when referring to various federal offices. Suffice it to say, the focus on the practical effect of Impeachment 2.0 will be markedly different than it was the first go-round. Any pro-Trump arguments will focus on which, if any, offices he should be legally able to hold in the future.

Given the numbers required under the Constitution, though, the likelihood is that a conviction of Trump would mean his disqualification from all federal offices. Of course, an impeachment or conviction might not have direct state-level consequences. However, nothing is to stop states from amending their own laws to prohibit a president convicted after impeachment from holding state office. New York State has already amended its laws to allow post-pardon prosecutions specifically for Trump, and there’s no reason to believe states could not act similarly with regard to disqualification for public office.

Bonus: Trump has no Twitter account, so he won’t be able to threaten witnesses while they are testifying.

The House is scheduled to vote on the article of impeachment on Wednesday.

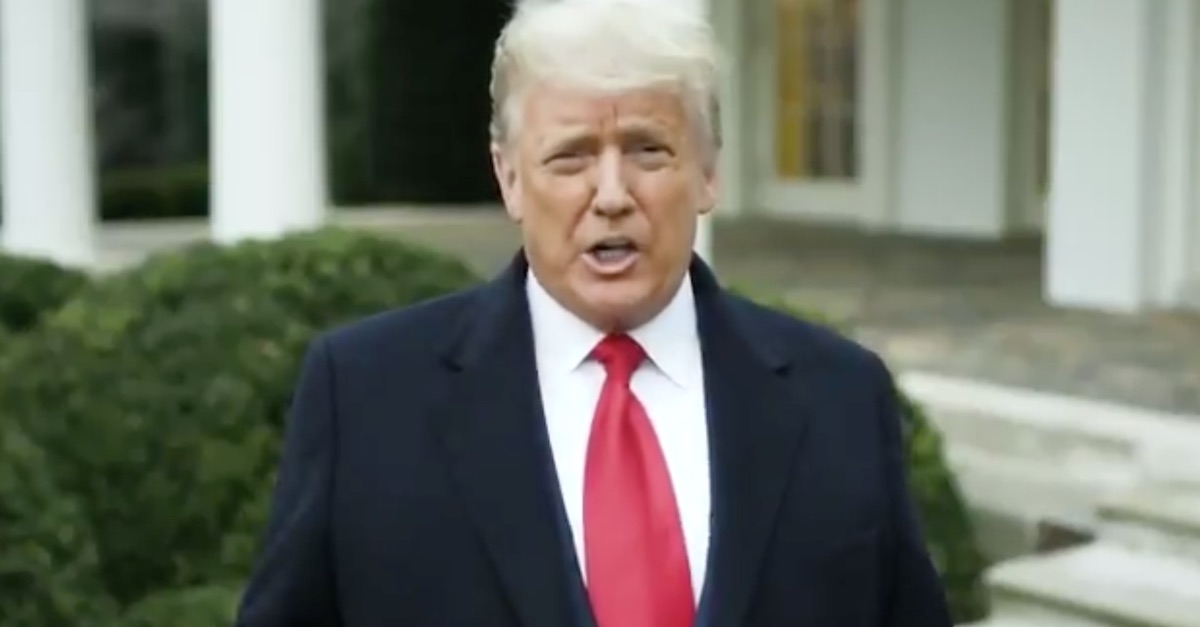

[image via Twitter/screengrab]