One of President Donald Trump‘s rumored Supreme Court finalists appears to have extreme views on the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. That potential nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, seems pretty hostile to the basic concept of Miranda rights.

Popularized by police procedurals like Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Miranda rights (also known as Miranda warnings) refer to a complicated legal framework which allows the accused–as well as those simply detained by law enforcement–to remain silent in the face of coercive questioning without their silence later being used against them.

In a law review article from 2010, Barrett wrote:

“[T]he Miranda doctrine, which inevitably excludes from evidence even some confessions freely given, is an example” of “the court’s choice to over-enforce a constitutional norm by developing prophylactic doctrines that go beyond constitutional meaning.”

Here, Barrett is essentially saying that the rights protected by Miranda warnings (the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution) are being unnecessarily protected by the same Supreme Court precedents which keep those rights intact.

Fashioned as more of a preventative rule of law enforcement procedure, Miranda warnings are usually given in order for confessions to remain admissible in later criminal proceedings. The Supreme Court has held that in the absence of such warnings, and by using confessions obtained without relaying the warnings, criminal defendants are denied their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and their Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

In other words, police and investigators can interrogate suspects without giving them Miranda warnings, but the information gathered from such interrogations would be subject to suppression under what’s known as the exclusionary rule. That is, an objection or motion to suppress would likely be filed in order to keep the information from being used to prove a defendant’s guilt.

The body of law, jurisprudence and procedure which collectively make up Miranda rights find their genesis in the 1966 Supreme Court case of Miranda v. Arizona. Since that decision and its dissemination into U.S. legal and law enforcement culture, each and every jurisdiction in the United States has fashioned their own version of the Miranda warning to ensure that police-obtained confessions remain admissible in court.

A common recitation of the Miranda warning comes courtesy of MirandaWarning.org:

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?

Various permutations of the above questions are commonplace and will survive Constitutional scrutiny so long as they effectively get the point across. Warnings that do not get the point across are likely not sufficient. The rights can also be waived.

The Supreme Court has had numerous occasions to revisit and restructure Miranda‘s essential thrust–and has thus far declined to do so. As former Supreme Court chief justice William Rehnquist noted in Dickerson v. United States:

We do not think there is such justification for overruling Miranda. Miranda has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture.

Barrett’s ascension to the Supreme Court would seemingly put her at odds with the justice elevated to the high court’s highest post by former president Ronald Reagan.

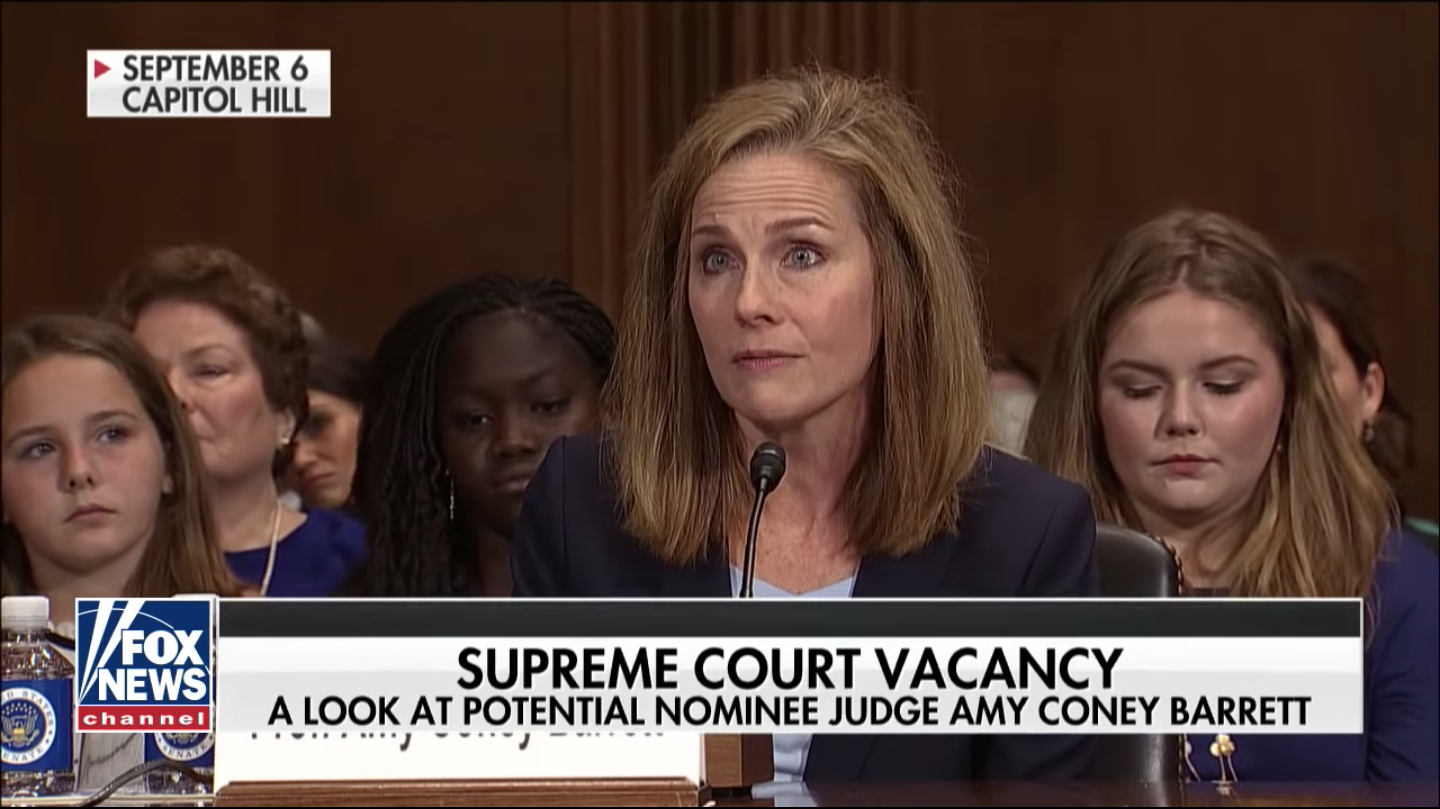

[image via screengrab/Fox News]