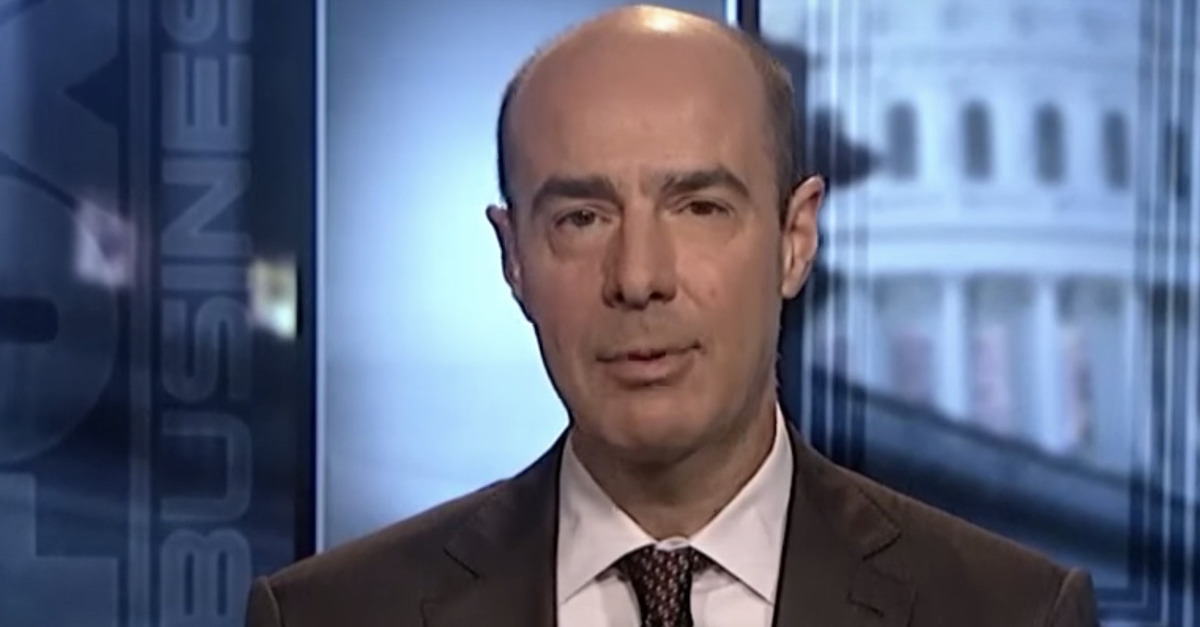

Secretary of Labor Eugene Scalia, the son of late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, has been sued by 17 states and the District of Columbia over the new “joint employer” rule.

The lawsuit, filed in the Southern District of New York, claims that rule “makes workers even more vulnerable to underpayment and wage theft,” while certain businesses see their liability for labor violations reduced.

“The Final Rule provides an incentive for businesses best placed to monitor [Fair Labor Standards Act] compliance to offload their employment responsibilities to smaller, less-sophisticated companies with fewer resources to track hours, keep payroll records, and train managers,” the plaintiffs allege. “It is estimated the Final Rule will cost workers, many of whom work at minimum wage jobs and live paycheck to paycheck, more than $1 billion annually.”

New York, Pennsylvania, California, Colorado, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington all argue that the implementation of the rule should be blocked because it violates the law–specifically the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). They sued Scalia in his official capacity, the DOL, and the United States.

“[T]he Final Rule is contrary to law because it is inconsistent with the FSLA’s statutory text and remedial purpose. In addition, the Final Rule expressly contradicts controlling Supreme Court authority interpreting the FLSA,” the lawsuit said. “Second, the Final Rule is arbitrary and capricious. The Department of Labor failed to justify departing from its longstanding interpretation of joint employment, and disregards evidence that this change will cause greater confusion among employers and employees. The Final Rule also fails to consider and quantify adequately the harms that the Final Rule will cause workers in terms of underpayment and stolen wages.”

The purpose of the rule, in the Department of Labor’s own words:

[It] specifies that when an employee performs work for the employer that simultaneously benefits another person, that person will be considered a joint employer when that person is acting directly or indirectly in the interest of the employer in relation to the employee;

provides a four-factor balancing test to determine when a person is acting directly or indirectly in the interest of an employer in relation to the employee;

clarifies that an employee’s “economic dependence” on a potential joint employer does not determine whether it is a joint employer under the FLSA;

specifies that an employer’s franchisor, brand and supply, or similar business model and certain contractual agreements or business practices do not make joint employer status under the FLSA more or less likely;

and provides several examples applying the Department’s guidance for determining FLSA joint employer status in a variety of different factual situations.

The rule is expected to go into effect on March 16.

Scalia’s appointment as Labor Secretary, which followed the high-profile resignation of Alexander Acosta, isn’t his first stint in government service. He served as the top legal officer at the Department of Labor during the George W. Bush administration, and as special assistant to Attorney General William Barr during his appointment by George H.W. Bush.

The Trump administration, a court recently found, ran afoul of the law when approving work requirements for Medicaid.

States Sue Eugene Scalia, DOL by Law&Crime on Scribd

[Image via Fox Business screengrab]