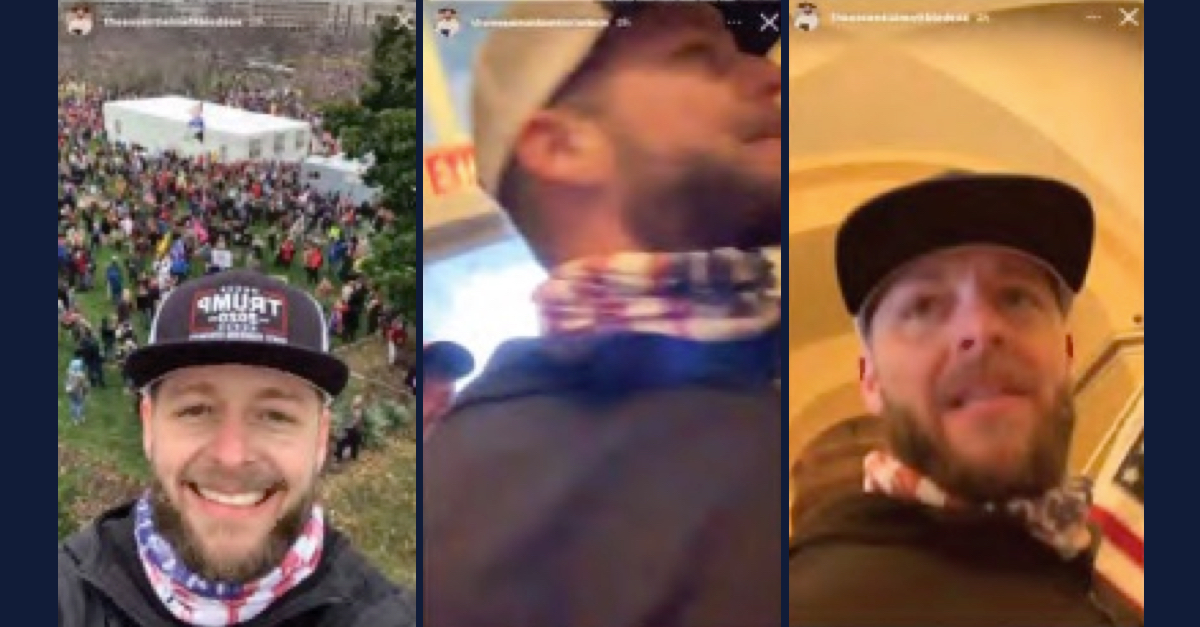

Matthew Bledsoe (via FBI court filing).

A federal judge in Washington, D.C., has ruled that the disclosure of location information provided by Facebook to the FBI about users inside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 did not violate Fourth Amendment privacy rights of a defendant who live-streamed his breach of the building.

Chief U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell issued the ruling Wednesday in the case of Matthew Bledsoe, 38, who was convicted by a jury in July of a felony and four misdemeanors in connection with the attack at the U.S. Capitol, when Donald Trump supporters, angry over the results of the 2020 presidential election, stormed the building as Congress had begun to certify the Electoral College vote count.

According to the government, Bledsoe scaled a wall at the Upper Northwest Terrace of the Capitol building and entered through a fire door at the Senate Wing. Once inside, prosecutors say, he climbed a statue and was outside the corridor to the House Chamber and hallways near the Speaker’s Lobby. He left after spending around 22 minutes inside.

According to court filings, Bledsoe live-streamed his activities at the Capitol to Facebook that day — evidence prosecutors recovered pursuant to a warrant after seeking user location information from the social media platform.

Before trial, Bledsoe filed a motion to suppress that evidence, arguing that both the government’s initial requests of Facebook and the subsequent search warrants were unconstitutional. Howell had denied his request days before trial started, indicating that a written ruling was forthcoming.

The judge filed that ruling on Wednesday.

In recapping the events of the day — including the fact that lawmakers and Capitol staffers were “evacuated under police guard and experienced the terror of hiding from the mob” — Howell noted that many in that mob were making documenting their experience.

“[M]any rioters celebrated this chilling historic moment by photographing and recording both themselves and others on restricted grounds surrounding and inside the Capitol Building and promptly posting their user-generated content online to various social media platforms,” Howell noted, adding that the breach of the building during as Congress was due to certify Joe Biden’s win was “nothing less than catastrophic.”

“Nothing About the Circumstances in Which These Account Users Found Themselves Even Hints at an Expectation of Privacy in Their Physical Location.”

The FBI, seeing that many rioters were posting pictures and videos from the Capitol as they were breaching it, requested identification information from Facebook that very day for account users who that had live-streamed their time at the Capitol. Specifically, the FBI asked that the platform identify “any users that broadcasted live videos which may have been streamed and/or uploaded to Facebook from physically within the building of the United States Capitol during the time on January 6, 2021, in which the mob and stormed and occupied the Capitol building.” The FBI then used that information to form the basis of probable cause affidavits that ultimately led to arrests and charges against accused Capitol rioters.

In making its request, the FBI relied on the federal Stored Communications Act, which allows providers such as Facebook to voluntarily provide records or other information related to a customer to the government “if the provider, in good faith, believes that an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to any person requires disclosure without delay of information relating to the emergency.” Notably, while information identifying the user may be disclosed, the content of such communications may not.

The FBI advised Facebook that it believed the rioters would commit other acts of violence and indeed posed a “future danger of an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury.” In response, Facebook made three disclosures to the FBI: one each on Jan. 6, Jan. 13, and Jan. 22, 2021. Federal prosecutors subsequently used information to form the basis of search warrants that would ultimately lead to arrests and charges against alleged Capitol rioters, including Bledsoe.

In seeking to suppress evidence derived from the search warrants, Bledsoe argued that the initial information voluntarily provided by Facebook violated his Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure, because he had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the non-content information Facebook provided. He also argued that the subsequent search warrant wasn’t supported by probable cause.

Howell disagreed.

The judge, a Barack Obama appointee, found that the defendant had not shown that he had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the user-generated location information (UGLI) provided by Facebook.

“[D]efendant fails to offer any factual support, and only sparse briefing, establishing how the requested information presents the same privacy concerns” identified in prior cases where a reasonable expectation of privacy did exist in location information, Howell wrote.

Howell said that Bledsoe “voluntarily conveyed” his location information to Facebook, citing the platforms Data Policy to which Bledsoe had agreed.

“[T]he only way that Facebook was able to determine when and where a user engaged in account activity on January 6, 2021, is by virtue of the user making an affirmative and voluntary choice to download the Facebook or Instagram application onto an electronic device, create an account on the Facebook or Instagram platform, and, critically, take no available steps to avoid disclosing his location, before purposefully initiating the activity of live streaming or uploading a video of a highly public event, in a manner that occurs during the normal course of using Facebook as intended,” Howell wrote. “Defendant has not identified a single instance where Facebook logs information concerning his account activity of posting any photo or video content on the Facebook platform without user action.”

Bledsoe had also relied on a Supreme Court case that had found that a cell phone user had a reasonable expectation of privacy as to much of their location information. In that case, the plaintiff had successfully argued that the use of a cell phone was “indispensable to participation in modern society” and that cell phones generated location data without any affirmative action of the user beyond simply turning on their phone.

Howell found that Bledsoe’s reliance on that ruling was misplaced, finding that the defendant had “failed to show that Facebook usage is essential to modern life.” The judge also noted that Bledsoe took significantly more affirmative steps to share his information to the social media platform than simply turning on his phone.

“[D]efendant, having ‘voluntarily conveyed’ information regarding user-generated account activity, i.e., a video of a highly public event either live-streamed from or uploaded to his Facebook account during the ordinary course of using Facebook’s services, cannot assert a reasonable expectation of privacy in Facebook’s disclosure of that information to the government,” Howell wrote.

The judge also noted that the government’s request for voluntary disclosure from Facebook was “narrowly circumscribed to reveal an account user’s presence in a government building (1) where ordinarily ‘[o]nly authorized people with appropriate identification are allowed access,’ (2) where serious criminal conduct occurred, (3) during an unprecedented national emergency, with concomitant national security implications, (4) while the user was surrounded by a mob numbering in the hundreds (or even thousands) and was engaging in broadcasting highly public activity through a social media platform [citations omitted].”

“Nothing about the circumstances in which these account users found themselves even hints at an expectation of privacy in their physical location,” Howell added. “Nor would any such expectation be one that society is prepared to accept as reasonable, especially considering the blatant criminal conduct occurring within the usually secured halls of the Capitol building during the constitutional ritual of confirming the results of a presidential election.”

Howell also found that the warrant to search Bledsoe’s social media was based on probable cause, rejecting the defendant’s premise that the government’s use of the word “may” in the warrant request “only establishes a possibility that the Facebook and Instagram accounts at issue might contain evidence of criminal activity.”

“The affidavit sets out a clear nexus between the content held in the social media accounts targeted by the search warrant and the multitude of criminal offenses committed within and around the Capitol Building,” Howell wrote. “Critically, the identified social media accounts were ones found to have engaged in broadcasting video content recorded or uploaded while the user was within the Capitol Building during the time of the riot.”

The judge found that Bledsoe’s reliance on the word “may” is “far too thin a reed to support suppression, given the full context and the known capabilities of Facebook, including those detailed in the warrant.”

Judge: Facebook’s Third Disclosure to FBI Raises ‘Serious Questions’ of Whether the Emergency Was Ongoing

Howell, however, had some critique of the government’s position. In a footnote addressing an alternative argument presented by the DOJ — which didn’t need to be addressed, thanks to Bledsoe’s failure to establish a reasonable expectation of privacy — the judge implied that the government hadn’t quite shown that Facebook’s Jan. 22, 2021 disclosure was based on a reasonable, good-faith belief that an emergency existed.

“The FBI agent’s declaration explaining the emergency circumstances prompting the initial request to Facebook contains no factual support establishing any objective reason to believe that sixteen days after the January 6, 2021 attack, either the FBI or Facebook reasonably believed that ‘law enforcement [was] confronted with an urgent situation,’ i.e., the need to protect congressional officers, law enforcement in the Capitol, or other individuals from threats of ‘imminent harm’ from rioters who participated in the January 6 attack,” Howell said in a footnote (emphasis in original).

Also conspicuously absent, Howell, added, was a declaration from Facebook offering specific reasons as to why the government’s Jan. 6 request was still considered an ongoing emergency as of Jan. 22.

“The record evidence shows that, on January 22, 2021, the FBI did not feel an urgent need to take action to identify the perpetrators of the January 6 attack based on Facebook’s disclosure since the FBI waited until February 7, 2021, sixteen days later, to search publicly available information on the Facebook accounts associated with the disclosed User IDs and to request that Facebook preserve the contents of the identified accounts, and waited until March 3, 2021, forty days later, to request a warrant to search the identified accounts,” Howell said (emphasis in original. “These time periods raise serious questions of whether, after the dispersal of the mob that attacked the Capitol building on January 6, 2021, by the end of that day and the increased security precautions then put in place through the Inauguration, the urgent need for the information initially requested on January 6 continued until January 22, 2021, to permit the FBI’s reliance on the emergency disclosure provision in [the Stored Communications Act].”

Bledsoe is set to be sentenced on Oct. 21. He faces up to 20 years in prison for felony obstruction, and a combined three years behind bars for the misdemeanor trespassing and disorderly conduct charges.

Read the ruling, below.

[Images via FBI court filing.]