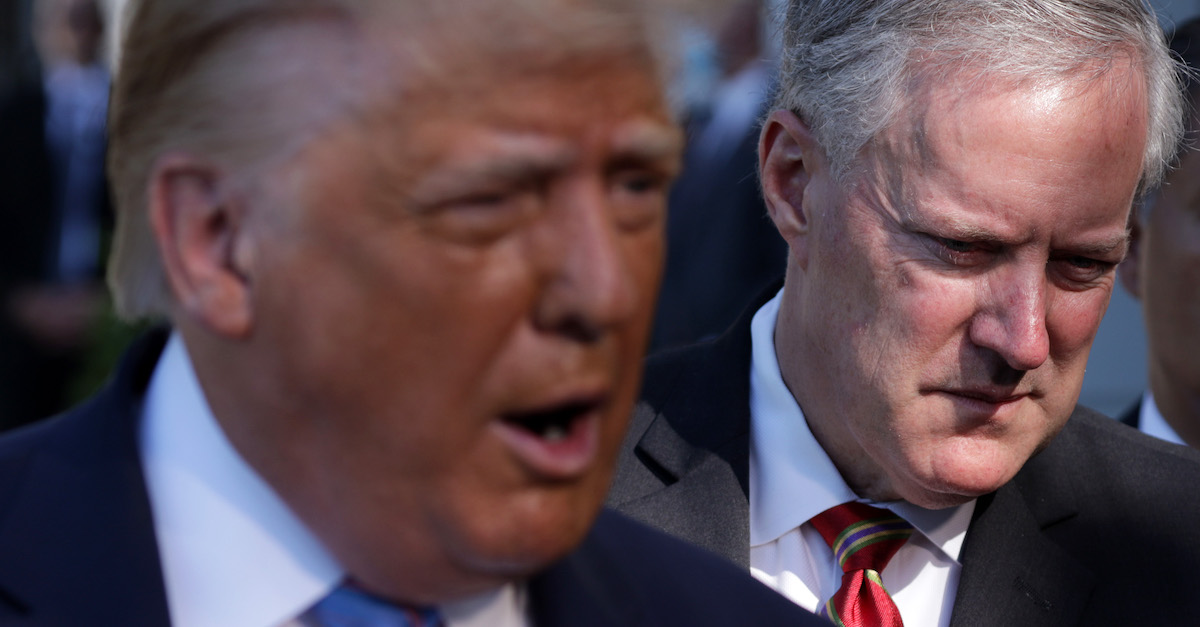

Donald Trump speaks as White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows (R) listens from the South Lawn of the White House July 29, 2020. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images.)

The House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol asked a federal judge late Friday night to shut down an attempt by Mark Meadows, the chief of staff of Donald Trump’s White House, to avoid answering subpoenas about what happened in the leadup to the deadly attack.

In a case styled as Meadows v. Pelosi, Meadows sued the Committee in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on Dec. 8, 2021. He asked a judge to “invalidate and prohibit the enforcement of two overly broad and unduly burdensome subpoenas” issued by the committee, according to the original complaint.

Meadows further asserted that the subpoenas were “issued in whole or part without legal authority in violation of the Constitution and laws of the United States.” More precisely, he argued that the “Select Committee wrongly seeks to compel both Mr. Meadows and a third party telecommunications company to provide information to the Select Committee that the Committee lacks lawful authority to seek and to obtain.”

An amended complaint was filed by Meadows on April 1, 2022.

The Committee moved late Friday to shut down the Meadows arguments. A motion for summary judgment asks a judge to declare the Committee the winner in the case and, in essence, to pave the way for the Committee to enforce its subpoenas with regards to Meadows.

“The Select Committee’s filing today urges the Court to reject Mark Meadows’s baseless claims and put an end to his obstruction of our investigation,” said a joint statement issued late Friday by Committee Chairman Bennie G. Thompson (D-Miss.) and Vice Chair Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.). “Mr. Meadows is hiding behind broad claims of executive privilege even though much of the information we’re seeking couldn’t possibly be covered by privilege and courts have rejected similar claims because the committee’s interest in getting to the truth is so compelling. It’s essential that the American people fully understand Mr. Meadows’s role in events before, on, and after January 6th. His attempt to use the courts to cover up that information must come to an end.”

The summary judgment motion, which spans some 248 pages with exhibits, declares that there are “no genuine issues of material fact” and that the Committee is “entitled to judgment as a matter of law” — the legal standard for summary judgment by a judge and without a trial.

The motion’s introduction points out the curious fact that Meadows has written a book but refuses to provide information to the Committee:

The Select Committee . . . is investigating the violent attack on our Capitol on January 6, 2021, and efforts by the former President of the United States to remain in office by ignoring the rulings of state and federal courts and disrupting the peaceful transition of power. Plaintiff Mark Meadows was President Trump’s White House Chief of Staff during the events at issue. But Mr. Meadows also played an additional and different role, along with members of the Trump campaign, Rudy Giuliani and others, in the President’s post-election efforts to overturn the certified results of the 2020 election. Mr. Meadows has published a book addressing a number of these issues and has spoken about them publicly on several occasions.

The document notes that Meadows provided documents to the Committee, including 2,319 text messages and privilege logs; Meadows then agreed to sit and talk on Dec. 8, 2021. However, he told the Committee the day prior — Dec. 7, 2021 — that he had changed his mind. He then filed the lawsuit that the Committee naturally seeks to torpedo.

Again, from the document (most legal citations omitted):

In his Amended Complaint, Mr. Meadows asserts a range of legal arguments purporting to justify his refusal to comply with the Select Committee’s subpoena. Each is deeply flawed as a matter of law. For example, Mr. Meadows argues that the Select Committee lacks an appropriate legislative purpose. But the D.C. Circuit in Trump v. Thompson, 20 F.4th 10, 37-38 (D.C. Cir. 2021), has already rejected that argument, recognizing “Congress’s uniquely weighty interest in investigating the causes and circumstances of the January 6th attack so that it can adopt measures to better protect the Capitol Complex, prevent similar harm in the future, and ensure the peaceful transfer of power.”

Similarly, two other courts have already rejected Mr. Meadows’s arguments that the Select Committee is improperly composed under House Resolution 503 or applicable House Rules, or that the subpoenas issued by the Select Committee are other wise infirm. As those and other courts recognize, the Constitution’s Rulemaking Clause compels deference to the House of Representatives’s interpretation and application of its own rules.

The document then asserts that the Committee has since progressed significantly in its work and has identified “seven discrete topics” of inquiry for Meadows. Those areas are defined as follows:

1. Testimony regarding non-privileged documents (including text and email communications) that Mr. Meadows has already provided to the Select Committee in response to the subpoena, and testimony about events that Mr. Meadows has already publicly described in his book and elsewhere;

2. Testimony and documents regarding post-election efforts by the Trump campaign, the Trump legal team, and Mr. Meadows to create false slates of Presidential electors, or to pressure or persuade state and local officials and legislators to take actions to change the outcome of the 2020 Presidential election;

3. Testimony and documents relating to communications with Members of Congress in preparation for and during the events of January 6th;

4. Testimony and documents regarding the plan, in the days before January 6th, to replace Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen with Mr. Jeffrey Clark so that the Department could corruptly change its conclusions regarding election fraud;

5. Testimony and documents relating to efforts by President Trump to instruct, direct, persuade or pressure Vice President Mike Pence to refuse to count electoral votes on January 6th;

6. Testimony and documents relating to activity in the White House immediately before and during the events of January 6th; and

7. Testimony and documents relating to meetings and communications with individuals not affiliated with the federal government regarding the efforts to change the results of the 2020 election.

“Mr. Meadows participated, as a functionary of the Trump campaign, in activities intended to result in actions by state officials and legislatures to change the certified results of the election,” the document later asserts. “Thus, under D.C. Circuit precedent, documents and testimony regarding events in this capacity are not subject to claims of executive privilege.”

The document also contains dozens of pages of exhibits of testimony obtained by the Committee. The materials indicate that a collection of Republican lawmakers, including Reps. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), Louie Gohmert (R-Texas), Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), and Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), were involved in talks aimed to prevent Joe Biden from taking office. That’s according to testimony from Meadows aide Cassidy Hutchinson.

“Did Mr. Perry support the idea of sending people to the Capitol on January the 6th?” Hutchinson was asked.

“He did,” she replied, according to a partial transcript.

According to Hutchinson’s testimony, Trump-affiliated attorneys Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, and Jenna Ellis supported using then-Vice President Mike Pence as part of their efforts to keep Trump in office. So were GOP Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert — and the aforementioned Reps. Perry and Jordan.

Hutchinson didn’t explain the specifics of those plans regarding Pence because she said she wasn’t privy to them. She characterized the discussions as “general correspondence” which suggested the “Vice President may be able to do” things to keep Trump in office.

“We should look into this,” Hutchinson said of those talks, according to her testimony. “We should explore these ideas.”

Giuliani was also part of Hutchinson’s communications around that time, the documents indicate. Here’s the Committee’s questioning about him:

Q You also say in that message, “Rudy is wandering around with more evidence.” What does that mean?

A Mr. Giuliani had information that he believed was credible enough to pause the electoral count that morning — or that afternoon.

Q Do you know what happened with that evidence?

A I don’t.

Q Do you know what Mr. Meadows’ view on that was, whether there was credible evidence to pause the electoral count during the joint session on January 6th?

A Mr. Meadows was always willing to hear ideas, as he never wanted information to go unheard and for it not to be perceived as legitimate information in case it was. But I don’t know his specific — I don’t know his specific mindset or opinions on which evidence was seen as more credible to him, if any at all. That’s something that you’d have to ask Mr. Meadows.

Meadows had been warned of violence on Jan. 6, Hutchinson further testified.

“I don’t want to speculate whether or not he perceived them as genuine concerns, but I know that people had brought information forward to him that had indicated that there could be violence on the 6th,” Hutchinson said as to Meadows, again per her testimony. “But, again, I’m not sure if he — what he did with that information internally.”

Among the other interviews attached to the motion was one with former Assistant Attorney General Steven A. Engel, who said that an idea was floated for the Office of Legal Counsel — the division of the U.S. Department of Justice that provides legal advice to the President and other executive branch agencies — to provide some advice to Pence on what he might be able to do when counting electoral votes. Also discussed was whether a criminal investigation could be launched into “allegations of election fraud.”

Steven A. Engel, who was then an assistant attorney general for the Office of Legal Counsel, appears in an official DOJ portrait.

According to Engel:

There was some discussion — I don’t remember who raised it, but just was simply, you know, the notion that criminal investigative techniques would be effective in a contested election is not really — it’s just not the way criminal investigations work. Criminal investigations are under much slower timeframes.

To the extent the question is we should be looking at allegations of election fraud in order to discover the facts that could lead people to change their minds or change their votes or to cancel votes, you know, it’s just that the timeframe didn’t work. You know, so, while the Department did look into allegations as they were made, ultimately sort of the tool of doing this is not the way elections are contested. They’re contested in civil courts, and they’re contested by the campaigns. So I think there was some discussion of that.

And then, I mean, Mr. Clark suggested that OLC provide a legal opinion to the Vice President with respect to his authority when it comes to opening the votes as the President of the Senate on January 6th.

And I shot down that idea, but I said — I said: That’s an absurd idea. The — you know, the Vice President is acting as the President of the Senate. It is not the role of the Department of Justice to provide legislative officials with legal advice on the scope of their duties. And — you know, and — not to mention it was 3 days from the date. OLC doesn’t tend to provide the legal opinions, you know, in those cases, you know, in that short timeframe.

And the President said: Yeah, no, that’s — that’s — nobody — nobody should be talking to the Vice President here. And —

He was cut off by another question, and no additional pages of the truncated transcript were provided in the court filing

The Committee’s retelling of the matter also noted:

Certain text communications with Members of Congress suggest that Mr. Meadows himself “pushed” for Vice President Pence to take unilateral action to reject the counting of electoral votes on January 6th. And while Mr. Trump’s widely publicized call with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger was ongoing, Mr. Meadows exchanged text messages regarding the call with another member of the Georgia government. In addition, Mr. Meadows communicated repeatedly by text with Congressman Scott Perry regarding a plan to replace Department of Justice leadership in the days before January 6th.

To the latter point, Richard Donoghue, an acting United States Deputy Attorney General from December 2020 to January 2021, described a meeting involving Trump, Pat Cipollone, Pat Philbin, Eric Herschmann, Jeff Clark, Jeff Rosen, Steve Engel, and himself. That two-and-a-half-hour meeting, per Donoghue’s testimony to the Committee, “was entirely focused on whether there should be a DOJ leadership change.”

Richard Donoghue appears in a Nov. 7, 2019 file photo from when he was a U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York. (Photo by Kena Betancur/Getty Images.)

“So the election allegations played into this, but they were more background than anything else,” Donoghue told the Committee in a conversation that became increasingly testy, according to the transcript:

And the President was basically trying to make a decision and letting everyone speak their minds. And it was a very blunt, intense conversation that took several hours. And Jeff Clark certainly was advocating for change in leadership that would put him at the top of the Department, and everyone else in the room was advocating against that and talking about what a disaster this would be.

Q What were Clark’s purported bases for why it was in the President’s interest for him to step in? What would he do, how would things change, according to Mr. Clark in the meeting?

A He repeatedly said to the President that, if he was put in the seat, he would conduct real investigations that would, in his view, uncover widespread fraud; he would send out the letter that he had drafted; and that this was a last opportunity to sort of set things straight with this defective election, and that he could do it, and he had the intelligence and the will and the desire to pursue these matters in the way that the President thought most appropriate.

Q You said everyone else in the room was against this. That’s Mr. Cipollone, Mr. Philbin, Mr. Herschmann, you, and Mr. Rosen. What were the arguments that you put forth as to why it would be a bad idea for him to replace Rosen with Clark?

A So, at one point early on, the President said something to the effect of, “What do I have to lose? If I do this, what do I have to lose?” And I said, “Mr. President, you have a great deal to lose. Is this really how you want your administration to end? You’re going hurt the country, you’re going to hurt the Department, you’re going to hurt yourself, with people grasping at straws on these desperate theories about election fraud, and is this really in anyone’s best interest?”

And then other people began chiming in, and that’s kind of the way the conversation went. People would talk about the downsides of doing this.

And then — and I said something to the effect of, “You’re going to have a huge personnel blowout within hours, because you’re going to have all kinds of problems with resignations and other issues, and that’s not going to be in anyone’s interest.”

And so the President said, “Well, suppose I do this” — I was sitting directly in front of the President. Jeff Rosen was to my right; Jeff Clark was to my left. The President said, “Suppose I do this, suppose I replace him,” Jeff Rosen, “with him,” Jeff Clark, “what do you do?” And I said, “Sir, I would resign immediately. There is no way I’m serving 1 minute under this guy,” Jeff Clark.

And then the President turned to Steve Engel, and he said, “Steve, you wouldn’t resign, would you?” And Steve said, “Absolutely I would, Mr. President. You’d leave me no choice.”

And I said, “And we’re not the only ones. You should understand that your entire Department leadership will resign. Every AAG will resign.” I didn’t tell him about the call or anything, but I made it clear that I knew what they were going to do. And I said, “Mr. President, these aren’t bureaucratic leftovers from another administration. You picked them. This is your leadership team. You sent every one of them to the Senate; you got them confirmed. What is that going to say about you, when we all walk out at the same time? And I don’t even know what that’s going to do to the U.S. attorney community. You could have mass resignations amongst your U.S. attorneys. And then it will trickle down from there; you could have resignations across the Department. And what happens if, within 48 hours, we have hundreds of resignations from your Justice Department because of your actions? What does that say about your leadership?”

So we had that part of the conversation. Steve Engel, I remember, made the point that Jeff Clark would be leading what he called a graveyard; there would be no one left. How is he going to do anything if there’s no leadership really left to carry out any of these ideas?

I made the point that Jeff Clark is not even competent to serve as the Attorney General. He’s never been a criminal attorney. He’s never conducted a criminal investigation in his life. He’s never been in front of a grand jury, much less a trial jury.

And he kind of retorted by saying, “Well, I’ve done a lot of very complicated appeals and civil litigation, environmental litigation, and things like that.” And I said, “That’s right. You’re an environmental lawyer. How about you go back to your office, and we’ll call you when there’s an oil spill.”

And so it got very confrontational at points.

The entire motion for summary judgment and the attached exhibits are all below: