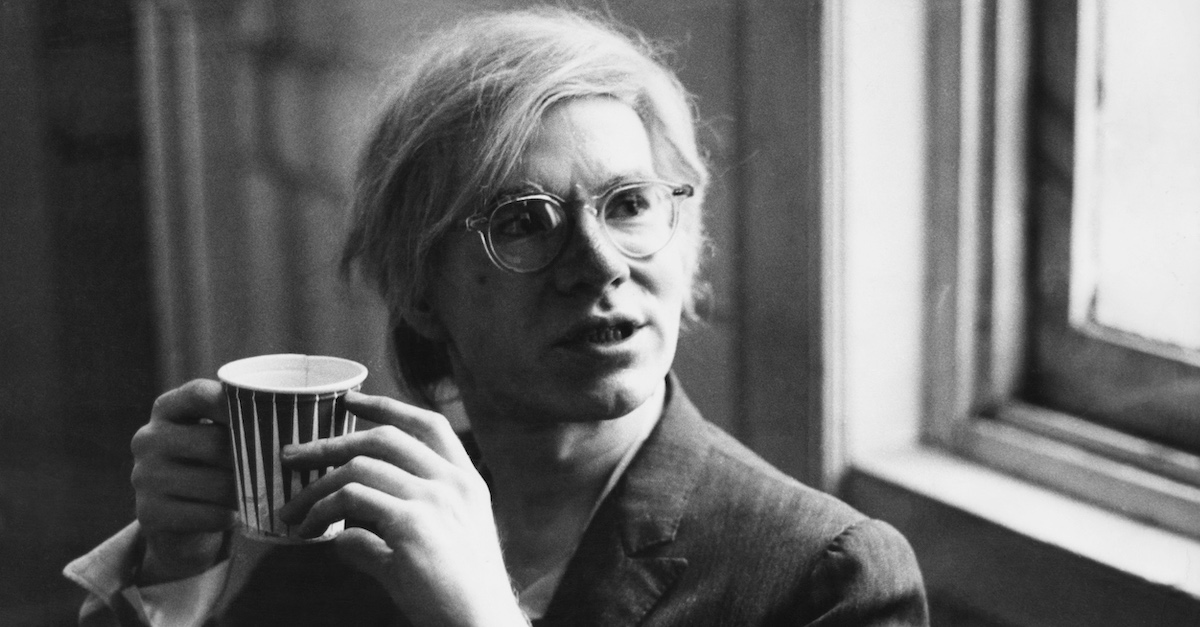

American pop artist Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987) holding a paper cup on Aug. 9 1971.

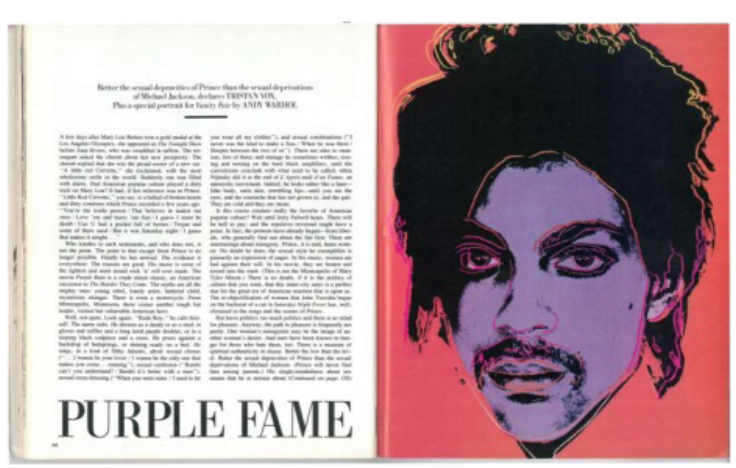

In a decision sure to shake up the art world and intellectual property law, the Second Circuit ruled on Friday that Andy Warhol’s series of silkscreens and pencil illustrations based on a Vanity Fair-commissioned photograph of the musical icon Prince does not clearly qualify as fair use.

The decision gives photographer Lynn Goldsmith another opportunity to sue the Andy Warhol Foundation for allegedly infringing upon an image taken at her studio in 1981.

When Vanity Fair commissioned Goldsmith’s photograph for an article on Prince, the magazine did not inform her that Warhol would be separately commissioned to turn that image into a silkscreen to signal the musician’s iconic Pop status. Goldsmith also did not know that the Pop artist extraordinaire would make 15 works based on that image that would become known as his “Prince Series.” She says that she learned of the series after Prince’s death in 2016.

The Warhol silkscreen published by Vanity Fair. (Screenshot from court papers)

After Goldsmith advised the Foundation of the perceived infringement, the matter headed to litigation the next year in the Southern District of New York. The Warhol Foundation preemptively sued seeking a declaration of fair use, and Goldsmith countersued alleging infringement. Goldsmith stumbled in the court of Judge John Koeltl, who found that Warhol transformed the “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” of Goldsmith’s work into an “iconic, larger than life figure.”

“That was error,” a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals found on Friday.

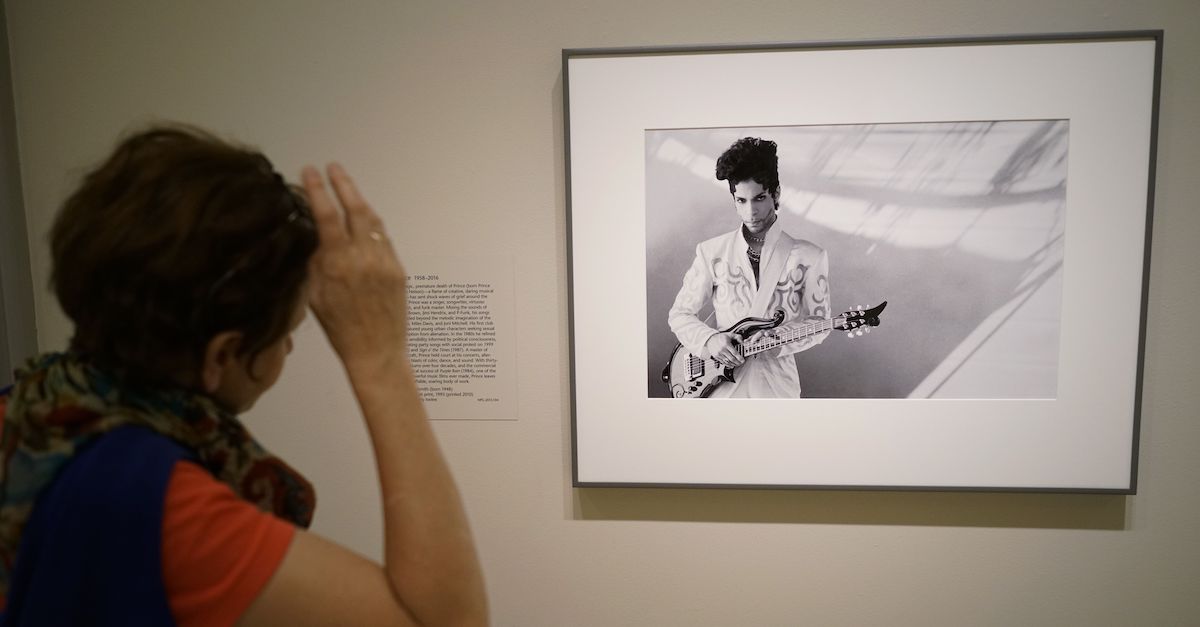

Visitors look at a 1993 photograph of musician Prince by Lynn Goldsmith at the Smithsonians National Portrait Gallery on April 22, 2016 in Washington, DC. (Photo credit: Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images)

“Though it may well have been Goldsmith’s subjective intent to portray Prince as a ‘vulnerable human being’ and Warhol’s to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon, whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work,” Circuit Judge Gerard Lynch wrote for the court. “Were it otherwise, the law may well ‘recogniz[e] any alteration as transformative.'”

The federal appeals court cautioned judges away from assuming the “role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.”

“That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective,” the ruling states.

The fact that each of the Prince silkscreens is instantly recognizable as a “Warhol” mattered little to the judges.

“Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others,” the ruling states. “But the law draws no such distinctions; whether the Prince Series images exhibit the style and characteristics typical of Warhol’s work (which they do) does not bear on whether they qualify as fair use under the Copyright Act.”

In reaching this finding, the judges emphasized that they do not mean to denigrate the legendary Pop artist.

“In reaching this conclusion, we do not mean to discount the artistic value of the Prince Series itself,” Lynch wrote. “As used in copyright law, the words ‘transformative’ and ‘derivative’ are legal terms of art that do not express the simple ideas that they carry in ordinary usage.”

Goldsmith expressed her gratitude for the decision in a statement to Law&Crime, through her attorney Thomas Hentoff of Williams & Connolly.

“Four years ago, the Andy Warhol Foundation sued me to obtain a ruling that it could use my photograph without asking my permission or paying me anything for my work,” she wrote. “I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work—and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so.”

The Warhol Foundation’s attorney Luke Nikas, a partner at the firm Quinn Emanuel, vowed to challenge the Second Circuit’s decision.

“Over fifty years of established art history and popular consensus confirms that Andy Warhol is one of the most transformative artists of the 20th Century,” Nikas told Law&Crime. “While the Warhol Foundation strongly disagrees with the Second Circuit’s ruling, it does not change this fact, nor does it change the impact of Andy Warhol’s work on history. The Foundation will continue to promote the ideals of artistic creativity and freedom of expression that are embodied in Warhol’s work, and will challenge the Second Circuit’s decision to ensure that these ideals remain protected.”

Circuit Judges Richard J. Sullivan and Dennis Jacobs agreed with the decision, and each wrote separately about how to further restrict transformative use, to the almost-certain chagrin of appropriation artists and proponents of liberalizing intellectual property law.

In his concurrence, Sullivan proposed an additional fair use factor to consider: “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

“Placing dispositive weight on transformative use while reducing evidence of market harm to an afterthought is difficult to square with the Supreme Court’s guidance that the fourth factor ‘is undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use,'” Sullivan, a Donald Trump appointee, wrote, citing the case of Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters.

“Indeed, we have previously explained that focusing on the importance of the fourth factor “is consistent with the fact that the copyright is a commercial right, intended to protect the ability of authors to profit from the exclusive right to merchandise their own work,” he added.

Jacobs wrote separately to emphasize that museums and collectors do not immediately need to draw up plans for litigation.

“It is very easy for opinions in this area (however expertly crafted) to have undirected ramifications,” Jacobs noted in his concurrence. “A sound holding may suggest an unsound result in related contexts.”

“The sixteen original works have been acquired by various galleries, art dealers, and the Andy Warhol Museum,” he continued. “This case does not decide their rights to use and dispose of those works because Goldsmith does not seek relief as to them. She seeks only damages and royalties for licensed reproductions of the Prince Series.”

The Second Circuit’s ruling could have reverberations for a different Prince—appropriation artist Richard Prince, who previously persuaded the same court to consider five of his works riffing on Patrick Cariou’s photographs were transformative in a watershed decision in 2013. Prince repeatedly gets sued for pushing the boundary of fair use and is currently under fire for blowing up Instagram posts on an epic scale in service of his art. That lawsuit remains active in the Southern District of New York, which is under the Second Circuit’s jurisdiction.

Update—March 26 at 3:16 p.m. Central Time: This story has been updated to add reactions by artist Lynn Goldsmith and counsel for the Warhol Foundation, along with additional context.

Read the ruling below:

(Photo by Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images)