President Donald Trump’s legal defense against impeachment isn’t really legal at all, according to a constitutional scholar who has been observing the Senate trial in person.

Frank Bowman is the Floyd R. Gibson Missouri Endowed Professor of Law at University of Missouri Law School. In a recent article for The Atlantic, Bowman noted an otherwise obvious infirmity at the heart of Trump’s case—the arguments make no sense.

First, it’s important to understand the basic contours of Trump’s position. These principles were previously laid down in a 171-page Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) memo and have more or less been repeated by Trump attorney Patrick Philbin.

According to the Philbin, DOJ OLC and the White House, any of the subpoenas issued by oversight committees in the U.S. House of Representatives prior to House Speaker Rep. Nancy Pelosi‘s (D-Calif.) official vote formalizing impeachment are not valid.

Bowman dispenses with this argument thusly:

The president’s position, incredibly, is that if an ongoing oversight investigation begins to produce evidence that might result in impeachment, the committees conducting that investigation somehow lose their subpoena authority until the whole House declares a formal impeachment inquiry. This is, not to put too fine a point on it, absolutely daft.

“[T]his is malarkey thinly draped with plausible-sounding distortions of facts, rules, court opinions, and the Constitution itself,” Bowman noted—apparently finding harsh rhetoric a handy hueristic to dispatch with the argument being advanced by Philbin, et, al.

But the constitutional scholar also explained why the president’s claims were just a bunch of meaningless jargon dressed up to give the appearance of law. And for that, he turns to our founding charter—the U.S. Constitution.

Bowman begins by accurately pointing out that the executive branch itself is only so large and powerful in the first place because of powers that have been gifted to the office of the presidency via the passage of bills that create federal agencies and continuing resolutions or other funding mechanisms that divert tax dollars to said agencies in order to keep the lights on. Without Congress, the president would lack almost all of the power and authority that office has accumulated to this date in history.

The author tidily explains:

[E]very single component of the executive branch other than the president himself exists only because Congress once passed a statute saying that it should, and thereafter enacted annual appropriations to provide for its continuance. Moreover, most of what the 2 million or so federal employees who staff the executive do every day is dictated by a congressional statute or a regulation promulgated pursuant to such a statute.

And, Bowman notes, with great power—even serially abdicated power—comes great responsibility over what goes on after the lights stay on.

Under Article II, he notes, “Congress has both a responsibility and a right to inquire closely into the operations of the federal agencies, programs, and employees it authorizes, regulates, and funds. The power of inquiry includes the power to use subpoenas to compel production of testimony and documents.”

Such inquiry-based powers have been tested and reaffirmed by the Supreme Court time and time again. Bowman also cites a law review article which itself cites the nation’s high court on this very matter.

An excerpt notes, in relevant part:

Congress’s power to investigate has deep roots in our political tradition, and the ability of Congress to investigate is embedded in our national charter, which gives Congress the power to legislate. As the Supreme Court has recognized, “[a] legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information—which not infrequently is true—recourse must be had to others who do possess it.”

In sum, Bowman describes an administration that’s waging war on America’s constitutional underpinnings themselves—in service of a onetime defense of a president credibly accused of violating and bypassing constitutional bounds and norms.

The White House’s necessarily self-serving defense, in the long run, reads like an all-out dismantling of congressional oversight as a concept. And, according to Bowman, this has not escaped at least some Republican members of the U.S. Senate because the logical end point of such an argument would effectively cancel their own power as well.

“The reason for the sudden attentiveness is not far to seek,” Bowman relayed—noting his first-hand observation of the GOP finally being observant last week. “Representative [Zoe] Lofgren was telling senators of both parties that Trump’s response to the House investigations that led to his impeachment was not merely a middle finger raised to Democrats, but an affront to Congress as a whole. She made clear that, left unrebuked, Trump’s defiance will gut the constitutional authority of both House and Senate not merely to check the personal excesses of any given president, but to oversee the entire executive branch.“

Law&Crime briefly caught up with Professor Bowman and asked point blank whether he felt Lofgren’s arguments would ultimately be taken seriously by Republican Senators.

”I think it unlikely that they will take it seriously in the sense of changing their votes,” he said—but hoped that the arguments put forward about fading congressional power would “at least avoid giving them an easy off-ramp” as they vote to acquit Trump by ceding “their own legitimate legislative authority.”

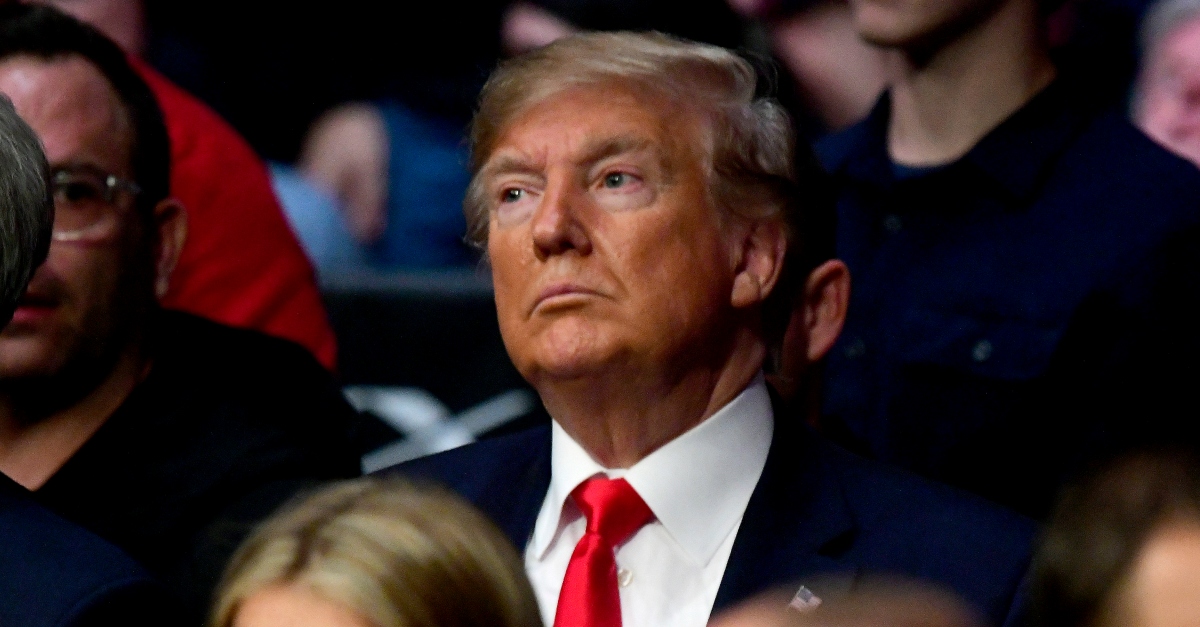

[image via Steven Ryan/Getty Images]