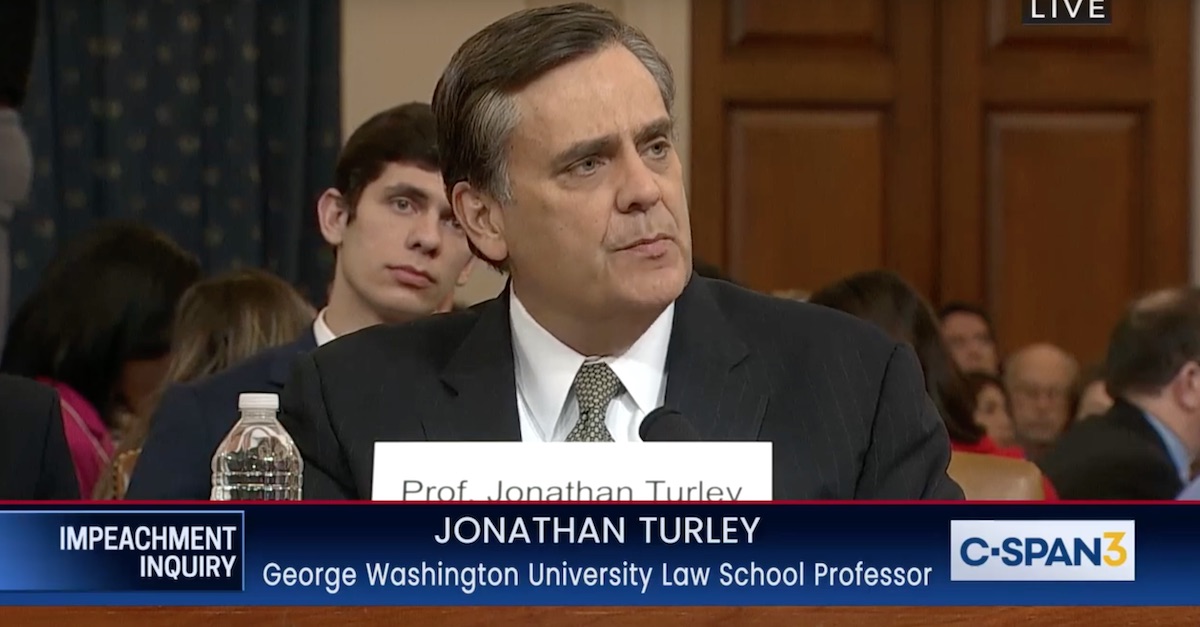

George Washington University Law Professor Jonathan Turley has something of a mixed record when it comes to his support for retroactive impeachment proceedings. And legal commentators made sure to highlight those apparent contradictions in light of President Donald Trump’s upcoming impeachment trial.

On Sunday, the Fox News contributor set things off with an opinion piece for Fox News arguing the Senate’s planned effort to vote on Trump’s removal and a potential ban on future office-holding faced something of a logical and constitutional shortcoming that made the whole effort, he claimed, somewhat dangerous to the U.S. Constitution’s “future.”

From that article:

On its face, the planned impeachment trial is at odds with the language of the Constitution, which expressly states that removal of a president is the primary purpose of such a trial. At the time, Trump will be neither a president nor in office. He will be a citizen and would be best served legally to forgo the trial entirely as extraconstitutional and invalid.

Turley went on to suggest that the 45th president–who will, of course, be merely wealthy citizen Donald Trump by the time the Senate takes up his historic second impeachment–should simply decline to show up for the Senate showdown at all.

“By declining to appear, the Senate would be faced with the glaring problem of holding a trial of a citizen to decide, under Article I, Section 4, whether he ‘shall be removed from office’ – after he already left office,” the constitutional law expert wrote.

Several other law professors and legal observers were quick to take issue with Turley’s advice and posture on the subject.

University of Texas Law Professor Steve Vladeck cited one lengthy passage from a 1999 Duke Law Journal article titled: “Senate Trials and Factional Disputes: Impeachment as a Madisonian Device.” In that article, Turley offered two arguably fulsome endorsements for retroactive impeachment.

That passage reads:

Accordingly, [William W. Belknap, the former secretary of war] was saved by two senators [in 1876] who believed that jurisdictional barriers prevented conviction. Fourteen Republicans defected to vote for conviction.

The most important aspect of the Belknap case was not his narrow escape but the trial itself. Members of both parties ultimately concluded that a trial of Belknap was needed as a corrective political measure. If impeachment was simply a matter of removal, the argument for jurisdiction in the Belknap case would be easily resolved against hearing the matter. The Senate majority, however, was correct in its view that impeachments historically had extended to former officials, such as [prominent British imperialist] Warren Hastings.

Impeachment, as demonstrated by Edmund Burke, serves a public value in addressing conduct at odds with core values in a society. At a time of lost confidence in the integrity of the government, the conduct of a former official can demand a political response. This response in the form of an impeachment may be more important than a legal response in the form of a prosecution. Regardless of the outcome, the Belknap trial addressed the underlying conduct and affirmed core principles at a time of diminishing faith in government. Absent such a trial, Belknap’s rush to resign would have succeeded in barring any corrective political action to counter the damage to the system caused by his conduct. Even if the only penalty is disqualification from future office, the open presentation of the evidence and witnesses represents the very element that was missing in colonial impeachments. Such a trial has a political value that runs vertically as a response to the public and horizontally as a deterrent to the executive branch.

Critics approvingly cited and recited–that is, tweeted and retweeted–Vladeck’s criticism of Turley.

The juxtaposition of the law professor’s apparent support for post-office-holding impeachment in the fall of 1999 (roughly two months before then-president Bill Clinton was impeached) and Turley’s opposition to post-office-holding impeachment now was met with serial accusations that he had become something of a hypocrite over the past 21 or so years.

North Carolina Law Professor Carissa Byrne Hessick took that criticism a step further and all-but accused Turley of making an ethical and professional departure.

“I appreciate that most people want to talk about this as Turley being hypocritical,” she wrote via Twitter on Monday morning. “But we should also see this as a serious breach of academic ethics and professionalism. Turley’s prominence in public discourse relies, in part, on his position as a professor—that status carries with it a claim to expertise on legal matters. Apparently his expertise led him to conclude the exact opposite of what he is claiming now on an issue of great importance.”

Turley, the lone expert witness called by the GOP during the House phase of Trump’s first impeachment, addressed some of his critics in a blog post on his personal website late Monday morning.

“This issue has not been a focus of my past writings – or the writings of most of us who have written on impeachment in prior years,” the George Washington University law professor noted. “I viewed it as an open question, but saw the value in such trials.”

“The Trump impeachments will force us to address new precedent for its implications of the process used in both impeachments,” Turley continued. “I have spent considerable time in the last few weeks drilling down on this issue. Some have noted my Duke piece recognized the value of impeachment trials beyond removal. That is true and it is certainly fair to note that my earlier writings can be used to argue for the value of such trials.”

Ultimately, however, Turley framed his shift as the process of intellectual evolution–and made a point to call out a similar evolution (in the opposite direction) by name.

Again his blog post, at length:

My point in these writings was to address the very narrow interpretations of impeachment offered by figures like Laurence Tribe. These scholars back then voiced a far more restrictive view of impeachment, declaring that lying under oath in the Clinton case would not be an impeachable offense. They are now espousing far broader interpretations of the language of Constitution. However, such views can change with time.

While only briefly addressed in my past writings, my view of this threshold issue has continued to evolve over the last 30 years. I still hold the prior views on the history and value of such retroactive trials. However, I believe that the language and implications of such trials outweigh those benefits. Indeed, I have found over these decades that departures from the language of the Constitution has often produced greater dangers and costs. I have become more textualist in the sense, but I am neither an originalist nor a strict textualist. It does not change my view of the meaning of high crime or misdemeanors, which was the focus of the piece. This is only a question of the jurisdiction of the Senate. If I were to write the Duke piece today, I would still maintain that it shows how impeachment trials serve this dialogic role but that I agree with roughly half of the Senate that trial was presumptively extraconstitutional.

The back-and-forth among the academics did not stop there.

“Except now he’s misrepresenting what he wrote. The Duke article wasn’t just about Hastings; it was also about Blount and Belknap,” Vladeck responded. “Not only did @JonathanTurley defend the validity of *both* post-resignation impeachments; he spent pages explaining why they were also a good idea.”

It would be one thing if he said “yes, I said that, but I was wrong — and here’s why.”

Instead, this is “I didn’t really say that, and there are good arguments on the other side.”

Even among Turley’s many convenient changes in position, this stands out for its shamelessness.

— Steve Vladeck (@steve_vladeck) January 18, 2021

Law&Crime reached out to Turley for additional comment and clarification on this article but no response was forthcoming at the time of publication.

[image via screengrab/C-SPAN]