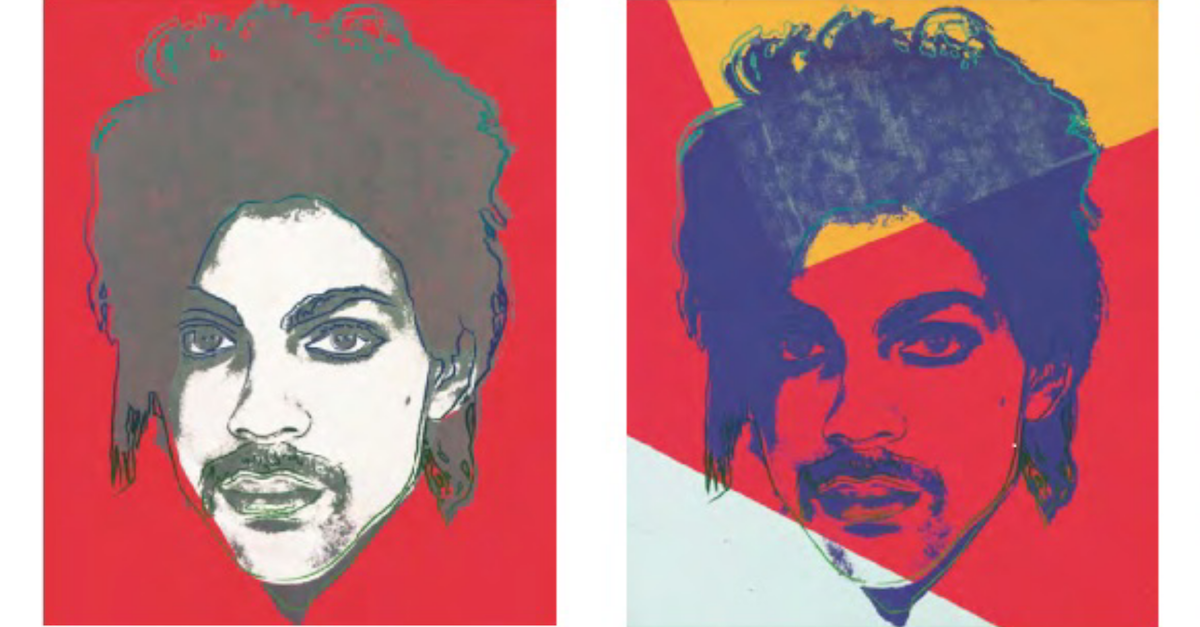

Court papers show silkscreens from Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series,” based on photographs from photographer Lynn Goldsmith.

The Supreme Court of the United States has agreed to take up the issue of fair use in a case involving decades-old silkscreens of the singer Prince by pop artist Andy Warhol.

The case stems from a series of paintings by Warhol in 1984 that used a 1981 picture by photographer Lynn Goldsmith of the late musician. Vanity Fair magazine had commissioned Warhol to create an image of Prince using Goldsmith’s photo for a story about Prince’s status as a pop music icon.

Warhol cropped Goldsmith’s picture of Prince—a black-and-white portrait of the singer looking directly at the camera—and used it as the basis for 16 silkscreened images in Warhol’s recognizable pop-art style that would become known as the “Prince Series.”

As Law&Crime previously reported, Vanity Fair did not tell Goldsmith that Warhol would create a new work based on her picture of Prince, and she didn’t learn of the series until after Prince’s death in 2016. When she told the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts that the series violated her copyright in the 1981 picture, the Warhol Foundation issued a preemptive strike, asking a federal court in 2017 for a declaration that the Prince silkscreens are protected under the fair use doctrine.

That doctrine extends legal protection to a work of art based on an existing work if the new piece is “transformative,” meaning it conveys a different “meaning or message” from its source material.

Goldsmith countersued, alleging copyright infringement, and in 2019 the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York found in favor of the Warhol Foundation. Warhol’s process of cropping the image to focus on Prince’s face, resizing it, altering the angle of his head, and adding layers of color, U.S. District Judge John Koeltl found, “transformed” Goldsmith’s intimate depiction into “an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” stripping Prince of the “humanity … embodie[d] in [the] photograph.”

The Warhol Foundation said that the Prince Series is a “comment on the manner in which society encounters and consumes celebrity.”

Goldsmith appealed, and the Second Circuit ruled in 2021 that the Prince Series did not clearly qualify as fair use, allowing her lawsuit against the Warhol Foundation to proceed.

Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Gerard Lynch, a Barack Obama appointee, wrote for the Second Circuit that Koeltl’s analysis relied too much on a single person’s perception of a work, and that could lead to overuse of fair use claims in art based on existing works.

“Though it may well have been Goldsmith’s subjective intent to portray Prince as a ‘vulnerable human being’ and Warhol’s to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon, whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work,” Lynch wrote. “Were it otherwise, the law may well ‘recogniz[e] any alteration as transformative.'”

On Monday, the Supreme Court granted the Warhol Foundation’s petition for a writ of certiorari to resolve the issue.

Representatives for the Warhol Foundation were pleased with the grant of certiorari.

“We welcome the Supreme Court’s decision to grant review in this case,” Roman Martinez, an attorney at Latham & Watkins, the firm representing the Warhol Foundation, said in a statement to Law&Crime. “The ‘fair use’ doctrine plays an essential role in protecting free artistic expression and advancing core First Amendment values. We look forward to presenting our arguments to the Court and hope they will recognize that Andy Warhol’s transformative works of art are fully protected by law.”

Andy Gass, another Latham & Watkins attorney focusing on copyright practice, said that the lawsuit was about more than a battle involving two artistic legends.

“The ‘fair use’ doctrine has for centuries been a cornerstone of creativity in our culture,” Gass said in the statement. “Our goal in this case is to preserve the breadth of protection it affords for all—from the Andy Warhols of the world, to those just embarking on their own process of exploration and innovation.”

Representatives for Goldsmith didn’t immediately respond to Law&Crime’s request for comment.

Documents in the case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith can be found here.

[Images via court documents.]