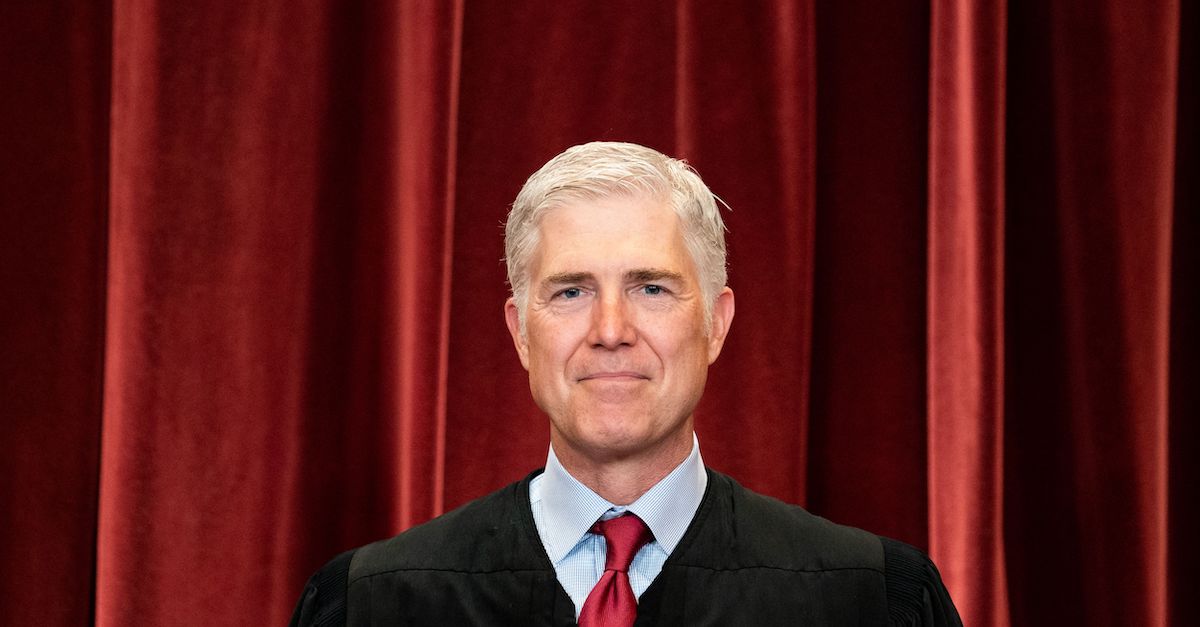

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch stands during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

In yet another unanimous opinion as the current term draws to a close, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled Tuesday against asylum-seeking immigrants in the companion cases of Garland v. Dai and Garland v. Alcaraz-Enriquez (previously captioned Rosen v. Dai and Rosen v. Alcaraz-Enriquez, respectively). The cases presented a procedural question that promises to have a profound impact on the cases of individuals seeking asylum in the United States.

The Court decided 9-0 that an appellate court must not presume an immigrant’s testimony to be credible when a lower court did not specifically address that person’s credibility. In a 15-page opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch repeatedly derided the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit for its practice of taking immigrants at their word when they are not entitled to such deference.

To be granted asylum, an immigrant must file a petition claiming their “life or freedom would be threatened” on account of “the alien’s race, religion, nationality, membership in particular social group, or political opinion.” If such a petition satisfies the fact-finding immigration court, then U.S. law mandates that the person must not be removed from American soil.

Given that many asylum-seekers arrive in the U.S. without supporting documents, immigration judges often rely solely on these individuals’ personal tales of persecution. When the immigration judge specifically deems an immigrant’s testimony credible, both the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and federal circuit courts will generally defer to that finding. However, when the immigration judge is silent on the immigrant’s credibility, different circuits handle the matter in different ways.

Justice Gorsuch, writing for the Court, explained that unlike other circuit courts, the Ninth Circuit has had a longstanding practice of assuming immigrants are being truthful, even when the immigration judge has made no such finding. He wrote:

For many years, and over many dissents, the Ninth Circuit has proceeded on the view that, “[i]n the absence of an explicit adverse credibility finding [by the agency], we must assume that [the alien’s] factual contentions are true” or at least credible. This view appears to be an outlier.

The Alcaraz-Enriquez and Dai cases each involve immigrants who petitioned to stay in the U.S., fearing persecution if returned to their home countries. In both cases, the immigrants were denied asylum by the presiding immigration judge and by the BIA; both immigrants appealed the denials to the Ninth Circuit, which in turn reversed.

Mexican-born Cesar Alcaraz-Enriquez came to the U.S. at age eight. His parents and siblings are all either U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents. Alcaraz-Enriquez has a history of serious mental illness, drug abuse, domestic violence, and time in prison. He has returned (both voluntarily and involuntarily) to Mexico several times over the years; each time, Alcaraz’s health deteriorates dramatically while in Mexico. His family wishes to care for him in the U.S.

Gorsuch walked through the disturbing facts of Alcarez-Enriquez’s criminal history.

The probation report indicated that Mr. Alcaraz Enriquez locked his 17-year-old girlfriend in his bedroom one evening, caught her trying to escape, dragged her back into the room, threatened to stab her and dump her body in a dumpster, and forced her to have sex with him. The next morning, he beat the young woman, leaving bruises on her back, neck, arms, and legs—stopping only when she begged for her life. Later that evening, when she asked to leave, he dragged her out, threw her against the stairs, and kicked her as she rolled down. Her ordeal lasted nearly 24 hours.

The immigration judge also considered Alcaraz-Enriquez’s testimony during his immigration proceeding; during that testimony Alcaraz-Enriquez admitted to hitting his girlfriend, but said he had been defending his daughter. He denied dragging and kicking his girlfriend and denied forcing her to have sex with him. Per the Court’s opinion, “He also submitted a letter from his mother, who stated that when she saw the girlfriend immediately after the altercation, ‘she looked completely fine.'”

The immigration judge threw out Alcaraz-Enriquez’s petition for asylum, and the BIA affirmed the decision. When the appeal reached the Ninth Circuit, though, that court, “saw the matter differently.” The Ninth Circuit applied its usual rule, “[a]nd because this rule required taking Mr. Alcaraz-Enriquez’s testimony as true—even in the face of competing evidence—the Ninth Circuit held that the BIA erred in denying relief and granted the petition for review.”

Gorsuch chastised the Ninth Circuit for applying its rule in the Alcaraz-Enriquez case, “disregard[ing] entirely the evidence contained in the probation report and credit[ting] only Mr. Alcaraz-Enriquez’s version of events.”

The Dai case offered very different underlying facts, but also culminated in the Ninth Circuit’s presuming credibility.

Ming Dai testified that, in 2009, officers came to his home in China where he lived with his wife and daughter. The Chinese officers forced Dai’s pregnant wife to have an abortion and to insert an IUD to prevent her from conceiving another child. They beat Dai and detained him for 10 days with minimal food and water. He contends that if he returns to China, he will be forcibly sterilized.

Gorsuch wrote that Dai’s testimony before the immigration judge, “cut both ways.” On the one hand,” the justice wrote, “Mr. Dai claimed that, after his wife became pregnant with their second child in 2009, family-planning officials abducted her and forced her to have an abortion. Mr. Dai further testified that, when he tried to stop his wife’s abduction, police broke his ribs, dislocated his shoulder, and jailed him for 10 days.” However, Dai left out some other important facts. “Mr. Dai failed to disclose the fact that his wife and daughter had already traveled to the United States—and voluntarily returned to China.”

After Dai “hesitated at some length” before the immigration judge, he admitted that his wife voluntarily returned to her job in China; he also admitted that he stayed in the U.S. saying, “at that time, I was in a bad mood and I couldn’t get a job, so I want to stay here for a bit longer and another friend of mine is also here.”

Although the immigration court ruled against Dai, “the Ninth Circuit saw things differently,” and ruled that Dai’s testimony must be “‘deemed’ credible and true,” because the immigration judge did not make a specific finding about Dai’s credibility.

Gorsuch slammed the Ninth Circuit’s approach as having “no proper place in a reviewing court’s analysis.” He continued, “Nothing in [immigration law] contemplates anything like the embellishment the Ninth Circuit has adopted.”

Essentially, the judges of the Ninth Circuit should have stayed in the appropriate judicial lane. Gorsuch wrote, “it is long since settled that a reviewing court is ‘generally not free to impose’ additional judge-made procedural requirements on agencies that Congress has not prescribed and the Constitution does not compel.”

The justice, however, cautioned his readers against interpreting the Court’s opinion too broadly. The ruling “does not mean that the BIA may ‘arbitrarily’ reject an alien’s evidence,” he explained. Rather, it means that if there is enough evidence to satisfy a reasonable fact finder, “a reviewing court may overturn the agency’s factual determination.”

In the context of immigration courts’ rulings in asylum cases, Gorsuch went on to explain that the Circuit Courts simply “review” the lower rulings; that is a contrast from other cases in which the courts handle true “appeals.” A court that sits in “review” has limited-scope authority.

“The only question for judges reviewing the BIA’s factual determinations,” wrote Gorsuch, “is whether any reasonable adjudicator could have found as the agency did.” The Ninth Circuit, though, went much too far. “The Ninth Circuit’s rule mistakenly flips this standard on its head. Rather than ask whether the agency’s finding qualifies as one of potentially many reasonable possibilities, it gives conclusive weight to any piece of testimony that cuts against the agency’s finding,” Gorsuch concluded.

[image via Erin Schaff/Pool/AFP via Getty Images]