Defense Attorney Eric Nelson introduces prospective jurors to Derek Chauvin during the voir dire process.

Peter Cahill, the judge overseeing the murder trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, issued an order late Wednesday which allows prosecutors to present some of Chauvin’s prior police actions to a jury in Chauvin’s upcoming trial surrounding the May 25, 2020 death of George Floyd, Jr. Opening statements in the case are scheduled for Monday.

In sum, the jury will hear evidence that Chauvin knew when a police restraint would become deadly because of an earlier arrest under similar circumstances to those posed by Floyd. The jury will also hear evidence that Chauvin unreasonably restrained one other suspect in the past. But Cahill said the jury would not hear about a rash of other incidents because he believed prosecutors were trying to unfairly taint Chauvin’s reputation by characterizing him as an aggressive cop.

In a 54-page ruling, Cahill spent nearly two dozen pages combing through the intricacies of body camera and bystander video of Chauvin’s restraint of Floyd before recapping the law which governs the admission of evidence involving a defendant’s “other acts.” Cahill decided that that two of the eight instances of Chauvin’s prior conduct which prosecutors sought to introduce to the jury would ultimately be admissible.

Under the Minnesota Rule 404(a), “[e]vidence of a person’s character . . . is not admissible” to prove a defendant acted “in conformity” with his character during the commission of an alleged crime. Similarly, under Rule 404(b)(1), evidence that a defendant committed “another crime, wrong, or act” in the past cannot be used to prove he’s simply a bad person who probably committed a new crime deserving of punishment.

The Minnesota Supreme Court has held the reason for the core rule is simple: “the jury may convict because of those other crimes or misconduct, not because the defendant” is guilty of the crime charged in the instant proceeding the jury must examine.

That’s not the end of the analysis. There are exceptions for specific uses by prosecutors of evidence of past conduct (which is legally distinct from character). The exceptions, which are also contained in Rule 404(b)(1), allowed Cahill to admit evidence of Chauvin’s past actions “for other purposes, such as proof of motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or accident.” Evidence of these so-called “other crimes” or “bad acts” is called Spreigl evidence in Minnesota; the name is derived from 1965 Minnesota Supreme Court case.

Minnesota’s Rule 404 is similar to, but not exactly the same as, the version Federal Rule 404 which was in effect before the restyling of the Federal Rules of Evidence effective December 1, 2011.

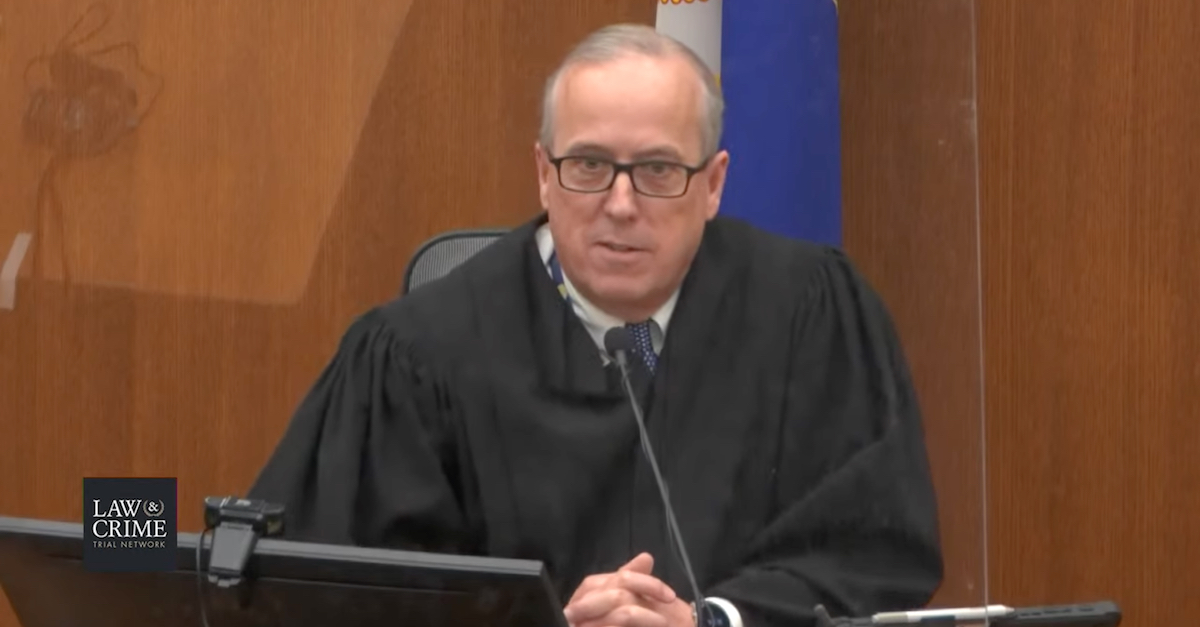

Judge Peter Cahill

Cahill is allowing the state to present incidents number 3 and 5 at trial.

Incident 3 occurred in 2015. In it, Chauvin and other officers provided aid to a “suicidal, intoxicated, and mentally-disturbed male” who was screaming “gibberish” and “Biblical chants” in his apartment, the judge’s order explains. Officers tased the man multiple times with no seeming effect. He survived his encounter with police. Chauvin and other officers placed the male into a “side-recovery position” after he was restrained; paramedics administered a sedative for the man’s own safety. The state says Chauvin later heard from hospital staff that the male could have died if police restraint techniques continued or if the male was not brought quickly for treatment. Chauvin and others received a “Lifesaving Award” for their handling of the case.

“This incident is offered to prove knowledge and intent,” prosecutors told the judge. “The incident demonstrates Chauvin’s knowledge of proper training to move a handcuffed person from the prone position to the side-recovery position and immediately seek medical aid. This incident proves that Chauvin intended to assault Mr. Floyd by continuing to hold Mr. Floyd in the prone position even after handcuffed and while Mr. Floyd was not resisting, or even responding.”

Judge Cahill ruled that the incident was important because it showed “Chauvin’s knowledge of the limits of reasonable force” in a similar incident to what George Floyd experienced in May 2020:

So long as the State presents evidence that Chauvin heard medical professionals making the statements about the potentially fatal risks to the man in those circumstances had he not been immediately placed into the rescue position by officers after being handcuffed and emergency medical professionals summoned, evidence of this incident is relevant to proving Chauvin’s knowledge about the importance and propriety of moving a handcuffed person from the prone position to the “rescue position” and obtaining immediate medical attention. That evidence would be relevant to establish Chauvin’s knowledge of the limits of reasonable force in analogous circumstances to those Floyd was manifesting on May 25, and thus could be relevant to the jury’s assessment of whether Chauvin’s conduct on May 25 constituted an assault when Chauvin chose to maintain his position kneeling on Floyd’s upper back and the back of his neck for some four minutes and forty seconds after Floyd had ceased resisting and uttering any sounds, had become motionless and non-responsive, and even after it appeared Floyd had stopped breathing and had no pulse. It may also be relevant to the jury’s assessment of whether Chauvin also deviated from the objective standard of care for the second-degree manslaughter charge. Finally, this evidence could be relevant to establishing Chauvin’s knowledge that failing to put a detained suspect exhibiting characteristics like those Floyd exhibited on May 25 into the recovery position is unreasonable and carries with it a serious risk of harm.

Incident 5 was a domestic assault call in 2017. A mother accused her daughter of trying to strangle her with a cord. When the daughter re-entered the home, Chauvin placed her under arrest. According to police reports cited in court documents, the daughter “kept twisting her body and trying to pull her arms in front of her,” so Chauvin “pulled her down to floor face first and kneeled on her to pin her body so we could finish handcuffing her.”

The daughter then refused to get up. Chauvin carried her outside, placed her face down on either the grass or the sidewalk (the various records conflict), pinned her to the ground, and placed her in a Hobble restraint — even though she was not resisting arrest. Per Judge Cahill’s recap of what occurred:

The body-worn camera video shows that Chauvin directed the other officer to apply the Hobble restraint in the “hog-tie” position, and Chauvin can be heard saying “perfect.” After applying the Hobble restraint, the officers placed the daughter in the back seat of the squad car on her side.

“This incident is offered to prove intent through modus operandi,” prosecutors told the judge. “In markedly similar circumstances, Chauvin pinned a handcuffed individual, who was not physically resisting, to the ground by placing his body weight through his knee to the person’s neck and upper back to maintain control of the person.”

Here, again, is why Cahill found the interaction important:

According to the State’s proffer, the only resistance the daughter offered was dragging her feet on the floor and briefly hooking a foot behind the television stand. When they had her out of the house, Chauvin placed her in the prone position on the sidewalk and kneeled on her back, directing the other officer to hog tie her even though by this time the woman was not making any threats and was not physically aggressive toward the officers. The State maintains Chauvin’s conduct in this incident is consistent with his behavior toward Floyd, who was fully handcuffed and, after several minutes after having been subdued prone on the street by Chauvin, Kueng, and Lane, had ceased offering any physical aggression. According to the State, Chauvin’s conduct in Incident No. 5 and during the encounter with Floyd on May 25, 2020 shows a common way of acting with suspects he believes may be intoxicated and who display any level of noncompliance while being taken into custody; in the State’s view, Chauvin operates in disregard for the particular circumstances of a given situation in determining appropriate reasonable force and simply fully restrains the suspect with no regard for their well-being until he can turn them over to someone else.

The State contends evidence of this incident is relevant not only to demonstrate Chauvin’s modus operandi in similar circumstances but may also be relevant to demonstrate his his intent to assault Floyd and to rebut his reasonable use of force defense by showing that Chauvin does not consider the individual circumstances in any given situation in deciding how much force to use or for how long but simply forces arrestees in the prone position to restrain them even after they have ceased resisting.

Cahill ruled that evidence of those two encounters with police were more probative than prejudicial as to the charges Chauvin currently faces.

Cahill believed prosecutors were attempting to offer the other six incidents simply to portray Chauvin as an overly aggressive cop who enjoyed deploying “unreasonable force”:

In this Court’s view, the real purpose for which the State seeks to introduce evidence of eight prior incidents in which it contends Chauvin exercised unreasonable force is simply to depict Chauvin to the jury as a “thumper,” an officer who knowingly and willingly relishes “mixing it up” with suspects and who routinely escalates situations and engages in the use of unreasonable force not warranted under the circumstances to subdue a resisting (or non-compliant) suspect. Stated otherwise, the actual purpose for which the State seeks to introduce evidence of all these prior incidents is as propensity evidence, portraying Chauvin as an officer who routinely resorted to unreasonable and disproportionate force when confronting noncompliant suspects in order to show that Chauvin’s conduct toward Floyd on May 25, 2020 likewise constituted the use of unreasonable and unauthorized force. That, of course, is improper and the evidence the State seeks to offer at trial of these other six incidents is therefore not admissible.

Cahill said the other incidents were not “remarkably similar” to George Floyd’s death and therefore were not admissible.

The judge somewhat sarcastically noted that the state did not charge Chauvin with assault over the other past incidents the state now seeks to use against the former officer.

As per Cahill’s order, here’s the verbatim list of Chauvin’s past incidents which prosecutors attempted to inject into the upcoming George Floyd trial:

Incident No. 1 — March 15, 2014:

On March 15, 2014, Defendant Chauvin restrained an arrested male in the prone position by placing his body weight on the male’s upper body and head area to control the man’s movement and to get him handcuffed. After placing handcuffs on both of the male’s hands, Chauvin had the male move to a seated position.Incident No. 2 — Feb. 15, 2015:

On February 15, 2015, Defendant Chauvin attempted to restrain a male, and when the male turned to face him, Chauvin applied pressure to the male’s lingual artery below the male’s chin bone. Chauvin told the man he was under arrest, and as the male was actively resisting, Chauvin pushed the male against a wall and applied a neck restraint and pressure. Chauvin then pulled the male to the ground, placed him in a prone position, and placed handcuffs on the male with the assistance of other security officers. Defendant kept the male handcuffed in the prone position until other officers arrived to aid him in placing the male in a squad car.Incident No. 3 — Aug. 22, 2015:

On August 22, 2015, Defendant Chauvin participated with other officers in rendering aid to a suicidal, intoxicated, and mentally-disturbed male. Chauvin observed other officers physically struggle with the male and one officer used a Taser on the male, to little avail. Eventually, the officers were able to put the male on the ground and place handcuffs on him. Chauvin and the other officers then immediately put the male in the side-recovery position, consistent with training. Chauvin rode with the male to the hospital for medical care. Officers involved in the response received a recommendation for an award for their appropriate efforts and received feedback from medical professionals that, if officers had prolonged their detention of the male or failed to transport the male to the hospital in a timely manner, the male could have died.Incident No. 4 — April 22, 2016:

On April 22, 2016, Defendant Chauvin informed a male that the male was not allowed to return to the property. When the male responded that he would not stay away, Chauvin restrained the male by placing both of his hands around the male’s neck and applying pressure to both sides of the male’s neck. Chauvin then forced the male backwards onto the sidewalk, handcuffed him, and then stood the male up and walked him to a squad car. A small crowd of concerned citizens gathered to view Chauvin’s conduct with the male. The male later complained of asthma, and paramedics were called to the scene.Incident No. 5 — June 25, 2017:

On June 25, 2017, Defendant Chauvin went to place a female under arrest in her home. As the female walked by, Chauvin grabbed one of her arms and told her she was under arrest. The female tried to pull away, and Chauvin applied a handcuff to one wrist. As the female tried to twist away, Chauvin pulled her down to the ground in the prone position and kneeled on her body to pin her to the ground. After being handcuffed, the female refused to stand, so Chauvin carried her out of the house in a prone position and set her face down on the sidewalk. Even though the female was not physically resisting in any way, Chauvin kneeled on her body, using his body weight to pin her to the ground while another officer moved the squad car closer. Chauvin then directed the other officer to apply a Hobble restraint to the female even though she was not providing any physical resistance. Chauvin’s conduct in kneeling on the female during this entire time was more force than was reasonably necessary under the circumstances.Incident No. 6 — Sept. 4, 2017:

On September 4, 2017, Defendant Chauvin responded to a domestic assault call with another officer. They attempted to arrest a juvenile male, and the male resisted. Chauvin applied a neck restraint to the juvenile male and rolled him onto his stomach. Chauvin used his own body weight to pin the juvenile male to the floor. Defendant continued to restrain the juvenile in this position beyond the point when such force was needed under the circumstances.Incident No. 7 — March 12, 2019:

On March 12, 2019, Defendant Chauvin directed a male to move away from a witness Chauvin and another officer were talking with. When the male refused, Chauvin approached the male, but the male pulled away, flailing his arms and struggling with the other officer. Chauvin sprayed mace at the male. The other officer directed the male to lay on the ground, and when he only kneeled, Chauvin applied a neck restraint to control the male. Chauvin forced the male to the ground and sat on the male’s back to pin him to the ground so he could be handcuffed. Chauvin restrained the male in this position beyond the point when such force was needed or reasonable under the circumstances.Incident No. 8 — July 6, 2019:

On July 6, 2019, Defendant Chauvin and another officer responded to a domestic assault call. When the male suspect dropped his arms down to his sides, Chauvin, concerned about access to knives, grabbed one of the male’s arms and delivered a kick to the male’s lower midsection to back him away. Chauvin thought the man had tensed up, so Chauvin applied a neck restraint. The male made a brief snoring noise, indicating the male had gone unconscious. During that time, Chauvin fully handcuffed the male.

Read the judge’s entire 54-page order below:

Derek Chauvin 404(b) Other … by Law&Crime

[images via the Law&Crime Network]