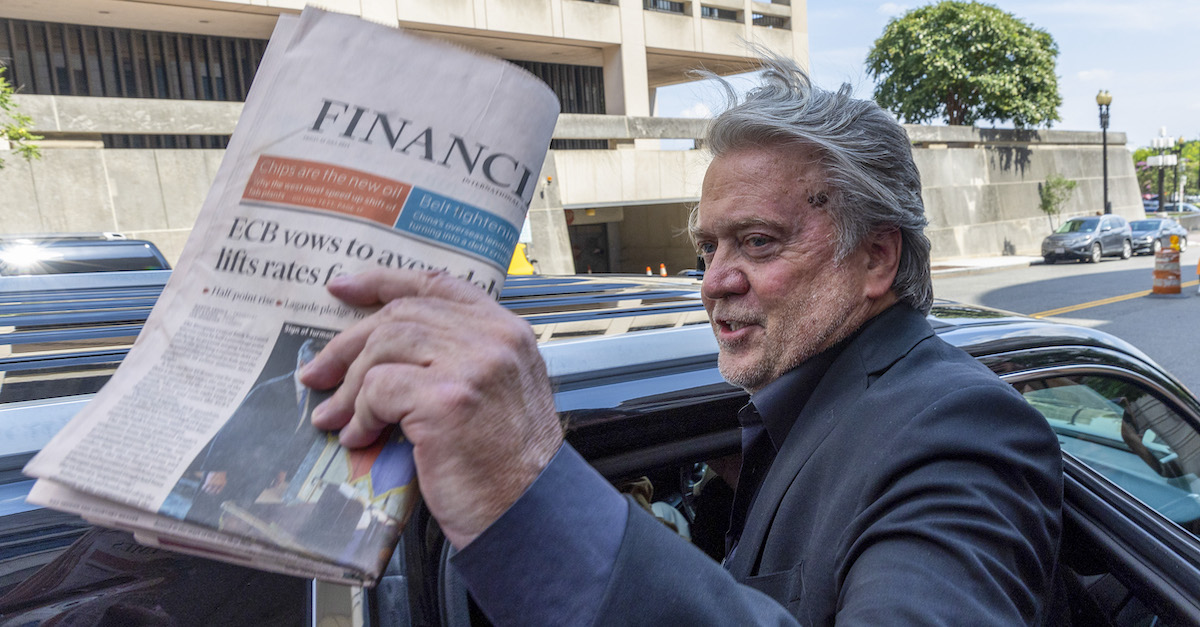

Former White House senior strategist Stephen Bannon was photographed leaving federal court on July 22, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images.)

Steven Bannon’s attorneys on Friday filed additional arguments in a post-conviction attempt to throw out an indictment that resulted in a contempt of Congress conviction for the former senior White House strategist.

“Throughout this case the prosecution has proceeded as if it has license to broadly mischaracterize the record and make whatever misrepresentations of fact it deems useful, all without consequences,” Bannon’s attorneys wrote in one footnote. “Highlighting these misrepresentations in the past has proven to be of no avail; so this practice will be ignored here, other than to note the special irony that such a practice is engaged in by representatives of the ‘public integrity’ division of the U.S. Attorney’s office.”

The defense has long argued that Bannon’s contempt of Congress indictment should be dismissed — a legal move that would nullify Bannon’s late July conviction despite the jury trial that resulted in a swift guilty verdict.

The case originated with a bifold request from the Jan. 6 Committee for the Trump confidant to supply both testimony and documents in a House probe of the attack on the U.S. Capitol Complex.

Most of Bannon’s eight-page Friday reply is a direct attack on a previous government move to rubbish Bannon’s last-ditch request to U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols to dismiss the indictment in the matter.

Both sides, in essence, have accused one another of either mischaracterizing the relevant law, twisting the facts, or failing to cite relevant legal authority.

“In typical fashion, the prosecution cites to cases in support of its position, while omitting fundamental details,” Bannon’s attorneys claimed.

The defense specifically pointed to case law they say gives it the right to force Judge Nichols to “balance” Congress’s Speech and Debate Clause privileges and Bannon’s own constitutional rights as a criminal defendant.

The DOJ has suggested that no balance is necessary in this case.

The issue surrounds a decision to allow a congressional representative, Kristin Amerling, to testify on behalf of the Jan. 6 Committee. Amerling is the Chief Counsel and Deputy Staff Director for the Committee.

Bannon argued that Amerling was allowed to testify on matters “for which she had no authoritative or decision-making role” in violation of his own rights under the Confrontation Clause. Bannon has expressed a preference to cross-examine witnesses “whose testimony and documents” he wished to probe — and to which he claims he was denied.

“Mr. Bannon also was denied his rights to a jury trial and to the effective assistance of counsel and his other fair trial rights by having the subpoenas quashed” as to witnesses other than Amerling, Bannon’s attorneys complained.

Bannon’s attorneys previously argued that the congressional witnesses they wished to examine refused to comply with subpoenas to provide documents and testimony that they believe would have been helpful to Bannon’s defense.

The eight-page reply filed Friday concludes with a request to quash Bannon’s indictment due to decisions which allegedly violated Bannon’s “fundamental constitutional rights.”

The DOJ previously said that Bannon’s attempt to secure additional witnesses and documents would have provided nothing of substance beyond that which was provided by Amerling. Prosecutors have called Bannon’s request for additional testimony and materials nothing but a fruitless and time-wasting “fishing expedition.”

“[I]ndeed, the Defendant does not even proffer what information his desired congressional witnesses would supply, because he does not know and can only speculate,” prosecutors wrote in the original document to which Bannon issued a reply on Friday.

A separate opposition document filed by prosecutors and dated Saturday in the district court’s electronic docket seeks to jettison Bannon’s separate request for an entirely new trial. In that request, Bannon claimed the court’s refusal to include certain jury instructions of his own choosing resulted in an “injustice.” Specifically, prosecutors claimed, Bannon wanted to inject his “desired meaning” of the word “willful” into the requisite contempt of Congress statute instead of using the “settled meaning” of that word under the law. Bannon also quibbled about jury instructions which defined the word “default” and a few other matters.

The DOJ reply argument explained those other matters, in part, as follows:

The Defendant seeks a new trial based on several claims of error in the instructions the Court gave the jury in this case and the Court’s adherence to controlling law defining the intent element of the contempt of Congress statute. The Defendant has failed to demonstrate that any of the issues he points to constitute error and has fallen far short of his burden to demonstrate that there is reason to doubt the validity of the verdict in this case. His motion should be denied.

“Motions for a new trial are not favored and are viewed with great caution,” prosecutors wrote while citing the underlying case law.

Here, prosecutors accused Bannon’s team of fudging the holding of Vicaria v. U.S., an 11th Circuit Court of Appeals case from 1994:

To the extent the Defendant cites Vicaria to suggest the Court can order a new trial based purely on the failure to give instructions the Defendant wanted, he is incorrect. Vicaria does not stand for such a sweeping proposition.

The out-of-circuit case does nothing to water down this circuit’s law that a new trial only should be ordered in circumstances of a serious miscarriage of justice based on an error likely resulting in an erroneous verdict.

And, prosecutors say, an “erroneous verdict” did not happen here:

The Defendant’s motion for a new trial fails to meet his burden . . . [h]e claims multiple errors without offering any basis to conclude they call the verdict into doubt, and the errors he claims are not, in fact, errors at all. Instead, he attempts to obtain a new trial by relitigating issues already decided by this Court, without offering any new basis to reconsider them, and by relying on misinterpretations of the evidence, this Court’s pretrial and trial rulings, and the controlling law. His motion should be denied.

Read the Bannon document (number 144) and the government document (number 145) below: