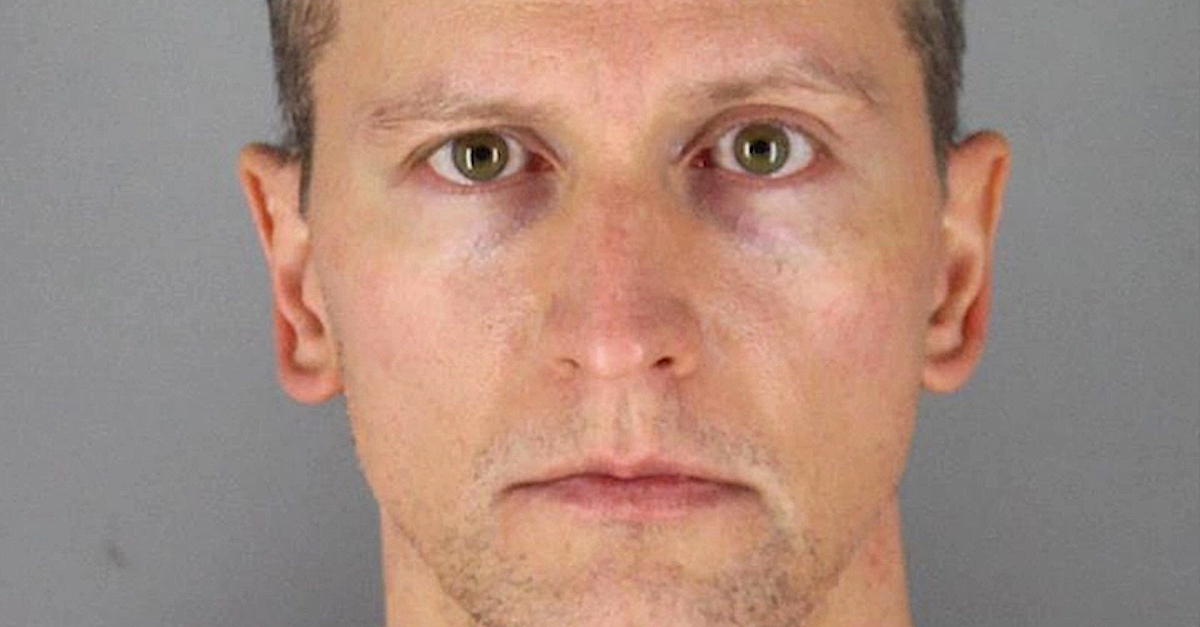

Derek Chauvin is seen in a Hennepin County Jail mugshot.

Prosecutors in the Derek Chauvin trial this week filed a 77-page motion which, in part, defends the juror who wore a “Get Your Knee off Our Necks / BLM” tee shirt and attended a Washington, D.C. rally before voting to convict the former Minneapolis police officer of murder in the death of George Floyd.

The juror, known in court papers as Juror 52, has publicly identified himself as Brandon Mitchell in several interviews, including one with the Law&Crime Network.

At legal issue right now is a lengthy voir dire interview given under oath during jury selection and a concomitant questionnaire which Mitchell filled out before being selected to determine Chauvin’s fate. Chauvin’s defense attorney, Eric J. Nelson, argues that Mitchell should have mentioned attending the rally and wearing the shirt before he was selected; Nelson says Mitchell’s failure to do so is among the reasons why Chauvin deserves a new trial.

Brandon Mitchell speaks to the Law&Crime Network after convicting Derek Chauvin.

Prosecutors countered that Mitchell was “honest and forthright” in voir dire and that no new trial is necessary. Here’s some of their argument (legal citations omitted):

In over 69 written questions and nearly 45 minutes of testimony, Juror 52 extensively detailed his preexisting views on a range of issues and his prior impression of this case. In his motion, Defendant identifies just one question, which Defendant believes shows that Juror 52 was “untruthful and evasive.” But that highly-subjective question asked whether there was “anything else the judge and attorneys should know about you.” Nothing indicates that Juror 52 necessarily intended to mislead by answering “no,” especially in light of Juror 52’s fulsome answers to a range of other questions, including his favorable opinion of the Black Lives Matter movement, his concerns regarding police misconduct, and his statements about his prior views on this case.

The prosecution said any defense misgivings connected to Mitchell’s conduct were “pure speculation that does not merit a . . . hearing.”

Prosecutors went into extreme detail describing why they believed Mitchell’s views on the written questionnaire were sufficiently honest and acceptable. Here’s the state’s lengthy recitation of Mitchell’s answers (again, with citations omitted):

In response to the very first question about his prior knowledge of the case, Juror 52 filled the entire page. He reported that he knew the incident had begun “with a fake bill or check,” that Mr. Floyd “ended up on the ground with Chauvin using his knee against Floyd’s neck to hold him in place,” that “Chauvin was on his neck for more than 8 min[utes],” and about public reporting regarding autopsies. Juror 52 also indicated that he had previously watched portions of the video of Mr. Floyd’s death 2-3 times, and that he had discussed the case with others. In response to a follow up question about the opinions he had expressed about this case, Juror 52 stated that he had wondered “why didn’t the other officers stop Chauvin.” For a question about whether he had seen police use more force than necessary, he wrote: “In downtown Minneapolis[,] I’ve seen police body slam then mace an individual simply because they did not obey an order quick enough.”

Nor did his responses, and his remarkable forthrightness, end there. Juror 52 indicated that he strongly agreed that “Blacks and other minorities do not receive equal treatment as whites in the criminal justice system,” that police officers are more likely to use force against black suspects, and that the criminal justice system is “biased against racial and ethnic minorities.” He wrote that he strongly disagreed that police “treat whites and blacks equally,” and that discrimination “is not as bad as the media makes it out to be.” He indicated that he somewhat agreed with the statement that “news reports about police brutality against racial minorities is only the tip of the iceberg.”

Juror 52 also wrote that he had a “[v]ery favorable opinion” of Black Lives Matter: “Black lives just want to be treated as equals and not killed or treated in an aggressive manner simply because they are black.” He indicated that he had neutral feelings toward “Blue Lives Matter,” and wrote this: “Although I do believe officers[’] lives matter, I feel like the concept ‘Blue Lives Matter’ only became a thing to combat Black Lives Matter, whereas it shouldn’t be a competition.” Juror 52 similarly wrote that he believed the criminal justice system “works, but also needs to be updated.”

On the last page of the questionnaire, in response to a question about whether there was “anything else the judge and attorneys should know about you in relation to serving on this jury,” Juror 52 answered “no.” In response to the next—and final question—Juror 52 then wrote that he wanted to serve on the case “[b]ecause of all the protest and every thing [sic] that happened after the event, this is the most historic case of my lifetime. Would love to be a part of it.”

The state then summarized Mitchell’s approximately 45-minute-long verbal voir dire, which the Law&Crime Network televised (once again, citations and parenthetical references are omitted):

He unequivocally confirmed that he could “listen to the entirety of the evidence in this case in an impartial manner,” and that he would set aside “any prior opinions” and “judge this case on the evidence as presented in court alone.” He similarly and unequivocally confirmed that he could “apply the facts, as [he] hear[d] them in court, to the law even if [he] disagree[d] with the law.” He explained that he felt unsafe when he saw police “slam[]” a kid “to the ground,” but that he knew police officers at his gym and “they’re great guys.” He also confirmed that one of his friends or relatives is a corrections officer. He explained his perspective on the Black Lives Matter movement: “It’s just people, black, you know, pigment, their lives matter. It’s just a statement.”

Defense counsel asked Juror 52 to explain his written answer that he wanted to serve on the jury because this was a historic case which had sparked protest. Juror 52 said: “[T]here’s no correlation between the protests and the facts. The facts are the facts. There is no correlation between those two things. . . . Me stating that this is possibly a historic moment is just based on the different movements that have come from this. That’s just—that’s just the fact of the matter.” The juror again confirmed that he could “listen to the facts and evidence in this case, apply the law, and be a fair and impartial juror.” Defense counsel passed on a for-cause strike and elected not to use one of Defendant’s many remaining preemptory challenges.

Prosecutors noted that Mitchell confirmed he could “follow the legal requirement not to hold [the] Defendant’s silence against him” and confirmed he would “set aside what [he] may have heard about any other information and only focus on what was presented in court.” Legally, Mitchell’s process of agreeing to set aside any preconceived notions — which is called the “rehabilitation” of a potentially biased juror — is of paramount importance when appeals courts examine whether pretrial bias really did affect a verdict. Appeals courts tend to take jurors at their word when they promise to set aside what they thought they knew about a case, and appeals courts also tend to also take jurors at their word when they vacillate or aren’t sure if they can set aside their thoughts to judge a case dispassionately.

In light of Mitchell’s written questionnaire answers and subsequent verbal answers, prosecutors say it’s preposterous for Chauvin’s defense to argue that Mitchell was “untruthful and evasive” for failing to bring up his attendance at a Washington, D.C. protest rally or his donning of the BLM tee shirt which contained the rallying cry of George Floyd’s supporters.

“Any fair reading of this record shows that Juror 52 honestly disclosed his views on a range of issues, including his impressions of Black Lives Matter, the criminal justice system, the case, and his desire to serve on this jury,” prosecutors argued. “Defendant does not contest Juror 52’s fulsome responses, either on the questionnaire or in voir dire. Nor does Defendant ever acknowledge Juror 52’s wide ranging and detailed answers in the material Defendant cites.”

Prosecutors then cut into the defense notion that Mitchell’s attendance at the D.C. rally somehow poisoned his ability to serve:

Defendant now claims that Juror 52 was “untruthful and evasive” in response to just one question, appearing on the last page of the questionnaire: “Is there anything else the judge and attorneys should know about you in relation to serving on this jury?” Defendant only argues that Juror 52 should have disclosed his participation in a march in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 2020. Defendant correctly characterizes the event as a “civil rights march.” For good reason: The march intentionally commemorated the anniversary of Dr. King’s famous march on Washington and his “I Have a Dream” speech, which took place on August 28, 1963, 57 years to the date before this march. But Defendant argues that any “reasonable person” in Juror 52’s shoes would necessarily have disclosed his “participation in a major civil rights march,” and his wearing a t-shirt with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s face and the slogan “get your knee off our necks * BLM.”

Citing case law, prosecutors then said the defense didn’t have the necessary legal footing to successfully challenge the juror’s attendance at the rally vis-à-vis his questionnaire, his voir dire answers, and his subsequent public comments about his jury service.

“Defendant’s claim falls well short of establishing a prima facie case of juror misconduct, and instead offers the kind of ‘wholly speculative’ allegation that does not ‘reasonably suggest[] that misconduct’ ‘occurred,'” prosecutors wrote, quoting Minnesota case law. “The question at issue asked the respondent to subjectively disclose ‘anything else.’ This generalized inquiry is a far cry from ‘the sort of clear question that, absent a lack of credibility on the juror’s part, necessarily would have elicited the disclosure of the sort of information that the [juror] withheld.'”

The prosecution accused Chauvin’s defense attorney of “materially misstat[ing] the record” surrounding Mitchell’s answers and statements.

Chauvin’s defense attorney raised other complaints about Mitchell in particular and about the Chauvin jury generally, but prosecutors said most of those complaints could not be relieved by post-conviction proceedings. That’s because Minnesota court rules and case law forbid — in most cases — the post-conviction probing of the secrecy of jury deliberations.

Read the state’s full 77-page document below; most of the discussion about Juror 52 begins around page 56: