A federal court of appeals ruled in Rep. Devin Nunes’ favor on Wednesday in a defamation lawsuit against reporter Ryan Lizza.

In ruling for the California Republican, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the underlying defamation claims over Lizza’s November 2018 Esquire article, “Milking the System.” In a legally novel turn, however, U.S. Circuit Judges Steven Colloton (who was appointed by George W. Bush), Lavenski Smith (another G.W. Bush appointee) and Ralph Erickson (who was appointed by Donald Trump) revived a claim by Nunes that Lizza libeled him when the reporter linked to the story in a November 2019 tweet.

“I noticed that Devin Nunes is in the news,” Lizza tweeted, after being sued by Nunes the month before. “If you’re interested in a strange tale about Nunes, small-town Iowa, the complexities of immigration policy, a few car chases, and lots of cows, I’ve got a story for you.”

The article in question focuses on why Nunes’s family sold their California dairy farm and “quietly” moved operations to Iowa. The article also alleges that Nunes and his family jockeyed to keep the move a secret. It notes that Nunes plays up the Golden State farm aesthetic in his political autobiography, while questioning whether the Nunes family farm in Iowa uses, or has in the past used, undocumented labor like so many farms in the Midwest.

Nunes lost at the district court level where all of his claims against Lizza and Hearst Magazine Media were dismissed. The appellate court largely agreed with their analysis but parted ways in two key aspects.

First, the higher court allowed a defamation by implication argument to survive, a claim that a series of published and/or omitted facts can be read as a whole to create a defamatory implication.

“Based on the article’s presentation of facts, we think the complaint plausibly alleges that a reasonable reader could draw the implication that Representative Nunes conspired to hide the farm’s use of undocumented labor,” Colloton reasoned in the 15-page opinion.

The ruling goes on to state:

Here, the article’s principal theme is that Nunes and his family hid the farm’s move to Iowa—the “politically explosive” secret. The article then sets forth a series of facts about the supposed conspiracy to hide the farm’s move, the use of undocumented labor at Midwestern dairy farms, the Nunes family farm’s alleged use of undocumented labor, and the Congressman’s position on immigration enforcement, in a way that reasonably implies a connection among those asserted facts. A reasonable reader could conclude, from reading the article as a whole, that the identified “secret” is “politically explosive” because Nunes knew about his family’s employment of undocumented labor. And revelation of that fact could be politically damaging to a Member of Congress who demonstrates “unwavering support for ICE” and who is among the “allies” of President Trump who have denounced “amnesty” for undocumented workers.

In the end, however, the reviewing court held that because of Nunes’s high-profile status, Lizza and Hearst were not acting with actual malice when the story was originally published. That is, Colloton and the other judges said there was no evidence that Lizza and Hearst acted “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The appellate court, in what scholars describe as a new application of U.S. law, couldn’t say the same for Lizza’s 2019 tweet wherein he re-shared the story.

Again, Colloton’s ruling, at length:

The complaint here adequately alleges that Lizza intended to reach and actually reached a new audience by publishing a tweet about Nunes and a link to the article. In November 2019, Lizza was on notice of the article’s alleged defamatory implication by virtue of this lawsuit. The complaint alleges that he then consciously presented the material to a new audience by encouraging readers to peruse his “strange tale” about “immigration policy,” and promoting that “I’ve got a story for you.” Under those circumstances, the complaint sufficiently alleges that Lizza republished the article after he knew that the Congressman denied knowledge of undocumented labor on the farm or participation in any conspiracy to hide it.

Previous district courts and circuit courts have reached exactly the opposite conclusions about hyperlinked stories but, the Eighth Circuit opined, “these decisions do not hold categorically that hyperlinking to an original publication never constitutes republication.”

The ruling quickly set off alarm bells among media attorneys, particularly those concerned with what appeared to be the appellate court’s erosion of First Amendment protections for the press.

Fordham Law Professor Matthew Schafer, who teaches a course on media law, said the decision was “awful in many ways” and singled out two aspects of the ruling that were “especially” worrisome.

“1) Tweeting a link to an article can be a republication of content in that article itself (CRAZY),” he tweeted. “2) Doing so after a lawsuit is filed is *prima facie* evidence of actual malice sufficient to avoid dismissal.”

In other words, if the panel’s ruling is allowed to stand, people who share articles that have been the subject of defamation lawsuits may be held liable if a plaintiff can adequately show that the person who shared the article had knowledge of the lawsuit’s existence. That is to say, the ruling takes the mere existence of a lawsuit as an actionable form of notice that such an article may contain defamatory falsehoods. That would mean that the typically high actual malice bar for politicians can easily be met if the allegedly defamed politician simply files a lawsuit.

“In a way, the decision okays gag orders – an intentional kill switch on an article after a lawsuit is filed,” Schafer continued. “That is, so long as a lawsuit with a denial is filed, the author of the article cannot redirect people to the original article on pain of waiving an [actual malice argument] on a [motion to dismiss].”

Texas Christian University Media Professor Chip Stewart had a similar take about the wide-reaching implications of the court’s ruling:

This is a mind-bending interpretation of libel law as it applies to social media. In short, a story that as a matter of law was *not* published with actual malice can be bootstrapped into a plausible libel lawsuit by a reporter tweeting the story *after* the lawsuit was filed. https://t.co/H8mhmEMzod

— Chip Stewart (@MediaLawProf) September 15, 2021

First Amendment lawyer Ari Cohn argued that the Eighth Circuit ruling amounts to judicial encouragement of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP suits).

This is not to downplay the horrible perniciousness of saying that if someone files a SLAPP suit to shut you up, they can automatically satisfy pleading standards on actual malice in a future suit *because* filed a SLAPP against you.

It’s a literal call to SLAPPs. Atrocious. pic.twitter.com/aO6j3Ufmrc

— Ari Cohn (@AriCohn) September 15, 2021

“Drawing attention to an already-published article just is not a republication, period. There has been no additional copy of the material created, and it is available to the exact same audience as it always has been,” Cohn said. “This is not to downplay the horrible perniciousness of saying that if someone files a SLAPP suit to shut you up, they can automatically satisfy pleading standards on actual malice in a future suit *because* filed a SLAPP against you.”

“It’s a literal call to SLAPPs. Atrocious,” he added.

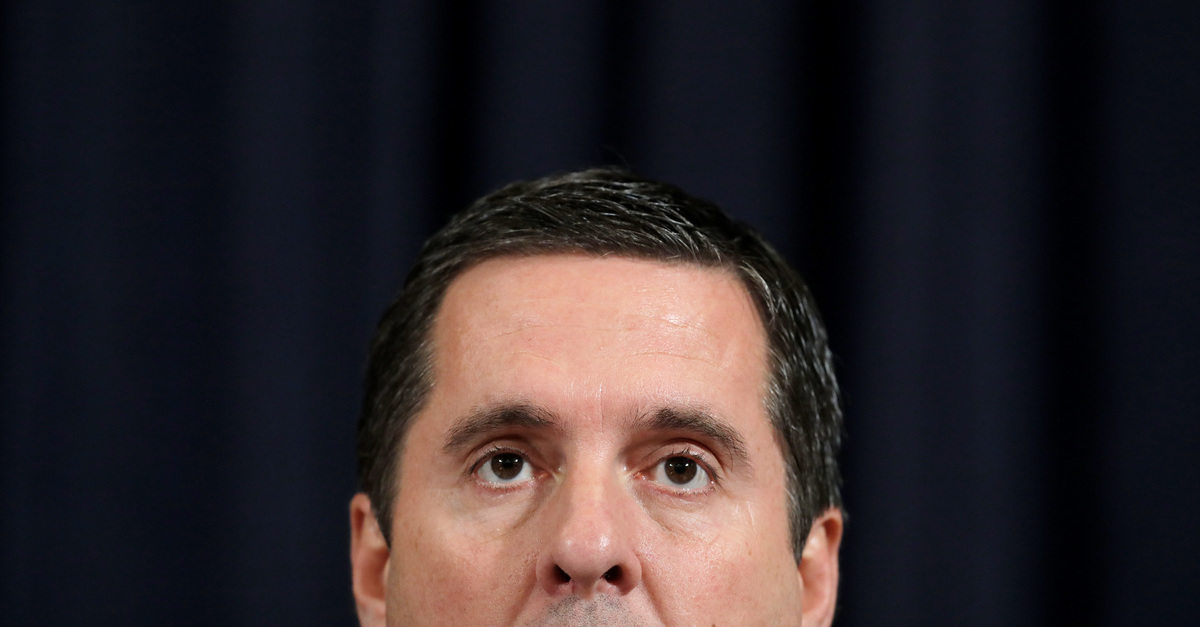

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]