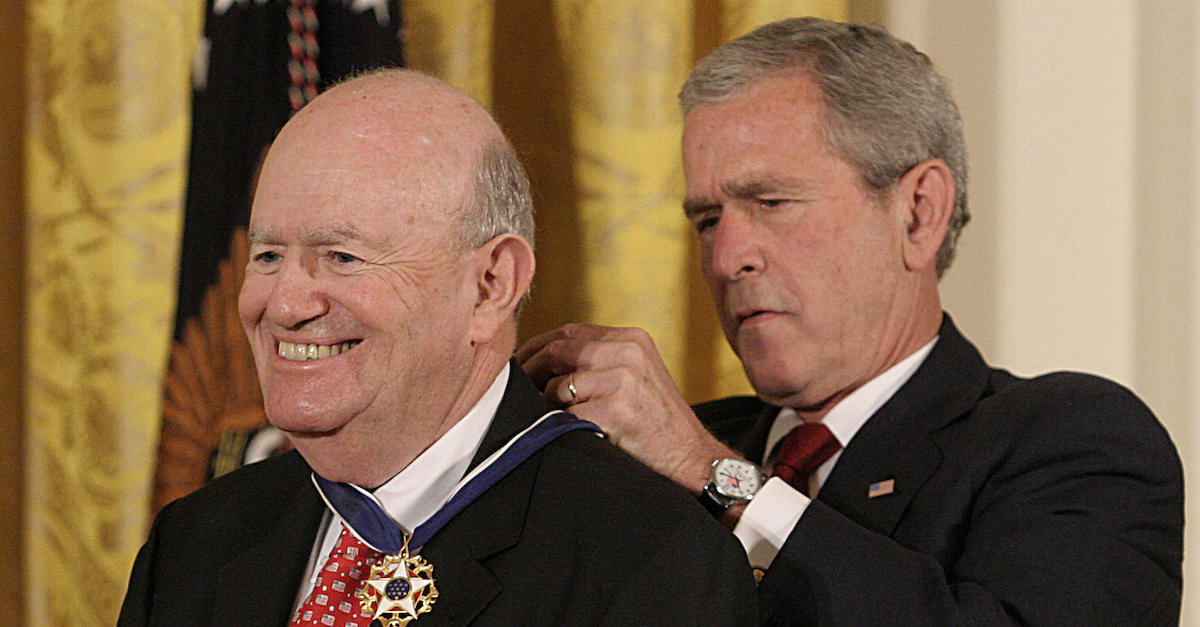

President George W. Bush presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom on June 19, 2008 to Laurence Silberman, Senior Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and co-chairman of the Iraq Intelligence Commission.

A Washington, D.C. federal appeals court judge spent a considerable number of pages in a Friday dissent rubbishing a U.S. Supreme Court case that is the pillar of the modern press press: New York Times v. Sullivan. While so doing, he slammed The New York Times itself, The Washington Post, and other major publications in the current media age for becoming “virtual[] Democratic Party broadsheets.” He also praised Fox News and The New York Post as “a lone holdout” that is “controlled by a single man and his son.”

The harsh words had absolutely nothing to do with the underlying opinion the judge, Laurence Silberman, was called upon to decide. Rather, they were part of a verbose dictum asserting that the press had become so powerful that its “bias[]” was “distort[ing] the marketplace” of ideas necessary for American democracy to function.

Implicit in Silberman’s logic is the idea that the press should be legally forced to pay increased economic damages in defamation actions because, in the judge’s view, the Supreme Court artificially and unconstitutionally gave the press too much power during the civil rights era of the mid-1960s — an era Silberman says has long passed into history and which bears little to no resemblance to modern America.

Let’s walk through opinion matter to understand the judge’s criticism.

In the underlying case, Tah v. Global Witness Publishing, Inc., a panel of three judges ruled that a lower district court judge properly dismissed a defamation action brought by “two former Liberian officials.” The officials “allege[d] that Global Witness, an international human rights organization, published a report falsely implying that they had accepted bribes in connection with the sale of an oil license for an offshore plot owned by Liberia.”

“The district court dismissed the complaint for failing to plausibly allege actual malice,” the 18-page majority opinion states. “For the reasons set forth in this opinion, we affirm. The First Amendment provides broad protections for speech about public figures, and the former officials have failed to allege that Global Witness exceeded the bounds of those protections.”

Circuit Judges Sri Srinivasan, David S. Tatel, and Silberman rounded out the panel. They are Obama, Clinton, and Reagan appointees, respectively. Silberman, 85, has been on senior status (semi-retired) since Nov. 2000.

Silberman issued a whopping 23-page partial dissent.

“Global Witness (Appellee) falsely insinuated that former Liberian officials (Appellants) took bribes from Exxon,” he stated. “It admitted that it had no evidence that Exxon had contacted Appellants, directly or indirectly, with respect to the alleged payments. And the evidence Global Witness did have suggested the payments at issue were proper staff bonuses, not bribes.”

He then throttled the majority for — in his view — “creat[ing] a whole new theory of the case . . . not advanced by any party.”

The majority rationed the Liberian officials who brought the action “were bribed not by Exxon, but by their own principal, the National Oil Company,” Silberman said. “Bribery, as it is commonly understood, involves a quid pro quo . . . in Global Witness’s story, it seems obvious that Exxon was the briber, Appellants were the bribees, and the trade was $35,000 to ensure the deal goes through. Without one element, there is obviously no bribery. In other words, if no briber—or no bribe—then no bribee.”

Global Witness, per Silberman, claimed its report was not defamatory — but “simply raised questions.” The judge took several pages unraveling the specifics of the report in question before the judge finally struck at the heart of New York Times v. Sullivan.

As Silberman explained, Sullivan is a 1964 U.S. Supreme Court opinion which “set forth the well-known rule” that a public figure plaintiff (such as a politician or someone otherwise famous) cannot win a defamation lawsuit unless a defendant publication acted with “actual malice.” That legal standard tests not whether the defendant hated the plaintiff but rather whether the defendant either (1) knew he was publishing a lie, or (2) published factual information “with reckless disregard” for whether it was true or false.

Republicans, including former President Donald Trump, have long complained that the standard makes it too difficult for public figures to recover defamation awards against reporters. The standard is based on the Constitutional presumption that the First Amendment freedoms of speech and of the press give reporters some additional leeway when publishing material about people who subject themselves to public scrutiny. It also encourages the press to dig into public officials such that voters may debate their qualifications for office.

“[A] story may be so facially implausible or factually flimsy that the jury may infer that it must have been published with reckless disregard for the truth,” Silberman explained while citing other cases. “If the publisher moves forward without reasonably dispelling his doubts, actual malice may be inferred.” Thus, the journalistic process requires fact checking.

Silberman said he believed Global Witness failed in that regard (emphases in original opinion):

In my view, because Global Witness’s story is obviously missing (at least) one necessary component of bribery, it is inherently improbable. Although it accused Appellants of taking bribes from Exxon, Global Witness admits that it had “no evidence that Exxon directed the [National Oil Company] to pay Liberian officials, nor that Exxon knew such payments were occurring.” In other words, despite all its investigating, Global Witness uncovered nothing to demonstrate that Exxon was the briber and nothing to even suggest there was an agreed upon exchange.

[ . . . ]

All the eyewitnesses to the transaction that responded to Global Witness explained precisely why it was wrong. And Global Witness had no facts that would cause it to discount these explanations.

The judge spent several pages going over precisely where he believed the report went off the rails, including that the defendant publication had six witnesses who disagreed that bribery occurred.

“Global Witness . . . did not have evidence on both sides of the issue,” the judge rationed. “It had ‘no evidence’ — and no witnesses — to contradict the six denials. The cumulative balance of the evidence thus gives Global Witness obvious reasons for doubt.”

Silberman then jabbed the court’s majority for what he argued was a misread of the underlying precedent:

The Majority’s opinion creates a profoundly troubling precedent. By fashioning a different defamatory implication on its own, the Majority embraces a telling example of judicial “creativity.” Still, its approach seems sui generis; I rather doubt we will ever see its like again. On the other hand, the Majority’s misunderstanding of the doctrinal framework of New York Times v. Sullivan’s actual malice concept is profoundly erroneous. And that will distort our libel law. But perhaps most troublesome is the conflict it creates with the Second Circuit (not to mention the Supreme Court) concerning the role of a court when . . . [analyzing a motion to dismiss] in the libel context.

[ . . . ]

After observing my colleagues’ efforts to stretch the actual malice rule like a rubber band, I am prompted to urge the overruling of New York Times v. Sullivan. Justice Thomas has already persuasively demonstrated that New York Times was a policy-driven decision masquerading as constitutional law. See McKee v. Cosby, 139 S. Ct. 675 (2019) (Thomas, J., concurring in denial of certiorari). The holding has no relation to the text, history, or structure of the Constitution, and it baldly constitutionalized an area of law refined over centuries of common law adjudication. See also Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 380–88 (1974) (White, J., dissenting). As with the rest of the opinion, the actual malice requirement was simply cut from whole cloth. New York Times should be overruled on these grounds alone.

Silberman said he realized it would be “difficult” to overrule the “landmark” New York Times case but said “new considerations have arisen over the last 50 years” which caused the case to become “a threat to American Democracy.”

“It must go,” he said.

Silberman then bragged that his logic led the U.S. Supreme Court to critically examine, but not overrule, another case involving qualified immunity. Four justices agreed with Silberman; he said the underlying cases about which he complained were “prime examples of rank policymaking by the High Court, not legitimate exercises of constitutional interpretation.”

He then returned a barb directed at him in a 1996 opinion by now-retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy. Kennedy suggested that judges should “guard against disdain for the judicial system” in an opinion which responded to Silberman’s criticism in the previous unrelated case.

“To the charge of disdain, I plead guilty,” Silberman responded in an attempt to apparently settle the approximately 25-year-old score. “I readily admit that I have little regard for holdings of the Court that dress up policymaking in constitutional garb. That is the real attack on the Constitution, in which—it should go without saying—the Framers chose to allocate political power to the political branches. The notion that the Court should somehow act in a policy role as a Council of Revision is illegitimate.”

Silberman then walked through the underlying history of the 1964 New York Times decision: the underlying matter there was a civil rights advertisement which a Southern official alleged defamed him. The battle between the Northern media of the day and the Southern establishment was clear: “CBS had similarly been sued for $1.5 million over a televised program that depicted the difficulties of African Americans in registering to vote,” Silberman noted.

But he then suggested that the same protections were unnecessary because today’s issues are different:

One can understand, if not approve, the Supreme Court’s policy-driven decision. There can be no doubt that the New York Times case has increased the power of the media. Although the institutional press, it could be argued, needed that protection to cover the civil rights movement, that power is now abused. In light of today’s very different challenges, I doubt the Court would invent the same rule.

As the case has subsequently been interpreted, it allows the press to cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity.

[ . . . ]

The increased power of the press is so dangerous today because we are very close to one-party control of these institutions.

[ . . . ]

It turns out that ideological consolidation of the press (helped along by economic consolidation) is the far greater threat.

In a footnote, Silberman alleges that “[a]s large American cities became heavily Democratic Party bastions, so too did the local dominant paper.”

He then returned to name names in the actual text of the opinion:

Although the bias against the Republican Party—not just controversial individuals—is rather shocking today, this is not new; it is a long-term, secular trend going back at least to the ’70s.

[ . . . ]

Two of the three most influential papers (at least historically), The New York Times and The Washington Post, are virtually Democratic Party broadsheets. And the news section of The Wall Street Journal leans in the same direction. The orientation of these three papers is followed by The Associated Press and most large papers across the country (such as the Los Angeles Times, Miami Herald, and Boston Globe). Nearly all television—network and cable—is a Democratic Party trumpet. Even the government-supported National Public Radio follows along.

[ . . . ]

To be sure, there are a few notable exceptions to Democratic Party ideological control: Fox News, The New York Post, and The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page. It should be sobering for those concerned about news bias that these institutions are controlled by a single man and his son. Will a lone holdout remain in what is otherwise a frighteningly orthodox media culture? After all, there are serious efforts to muzzle Fox News.

After alleging that there is similar bias at “academic institutions” and among Big Tech companies, the judge wrapped up the missive with the following:

It should be borne in mind that the first step taken by any potential authoritarian or dictatorial regime is to gain control of communications, particularly the delivery of news. It is fair to conclude, therefore, that one-party control of the press and media is a threat to a viable democracy. It may even give rise to countervailing extremism. The First Amendment guarantees a free press to foster a vibrant trade in ideas. But a biased press can distort the marketplace. And when the media has proven its willingness—if not eagerness—to so distort, it is a profound mistake to stand by unjustified legal rules that serve only to enhance the press’ power.

Read the full opinion below:

Tah v. Global Witness Publishing, Inc OPINION by Law&Crime on Scribd

[image via Karen Bleier/AFP/Getty Images]