President Donald Trump is threatening some form of criminal consequences over the publication of a forthcoming memoir penned by his former National Security Advisor John Bolton. Legal experts believe this situation poses both novel and well-settled questions regarding the extent of press freedoms guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution.

“I will consider every conversation with me as president highly classified,” Trump told reporters on Monday–predicting that Bolton was likely to face “criminal problems” should the publication of the book proceed as scheduled and as currently written.

Attorney General Bill Barr also waded into the controversy–suggesting that he, too, disapproved of Bolton’s long-delayed tell-all.

“This is unprecedented, really,” Barr said at the White House roundtable discussion. “I don’t know of any book that’s been published so quickly while, you know, the officeholders are still in government and it’s about very current events and current leaders and current discussions and current policy issues, which–many of which are inherently classified.”

According to Trump and Barr, the specific point of contention is that Bolton failed to complete a pre-publication review intended to remove any potentially classified material from a manuscript prior to publication. Bolton’s attorney Chuck Cooper has cried foul, however, insisting that his client has been working for months with National Security Council classification specialists toward exactly that end.

The controversy has raised evergreen issues about censorship and potential liability for publication of allegedly classified material. The First Amendment largely protects against the former and is generally understood to be something like an absolute barrier to the latter.

National security attorney Bradley P. Moss sought to distinguish Bolton’s situation from the governing Supreme Court precedent.

“I am skeptical the NYT/Pentagon Papers ruling from the 70s saves the publisher,” he wrote in a series of tweets. “It definitely would not protect Bolton if, for example, he announced his intention to self-publish. It obviously would apply to protect a newspaper if, for example, he had simply leaked it to them (that’s the Pentagon Papers fact scenario all over again). But this is different.”

“Bolton was paid by the publisher to write a tell-all book and to let the publisher distribute it for him for money. The publisher has already been producing copies and release is set for next week. The publisher has physical control over the copies. So where does the publisher fall here under the NYT precedent? They’re not just a part of the press: they paid for the rights to own and publish the material, and they will he compensated for selling the copies.”

National Security Counselors Executive Director Kel McClanahan disagreed–calling Moss’s take a “wrong opinion” based on a conversation between the two attorneys about the legal issues implicated in the Bolton-book-publication controversy.

“So, in a nutshell, the loophole that we were arguing about is whether there is a meaningful difference between a newspaper running a story (which can’t be prior restrained) and a publisher printing a book it paid someone for (which Brad thinks might be susceptible),” he said–also in a thread on Twitter. “The exchange of money is what makes the difference in his mind, while I maintain that this would be untenable, since it would mean that someone who got paid to write an op-ed would have less rights than someone who didn’t, that freelance reporters would have less rights than staff reporters, you would lose [First Amendment] rights as soon as you got a book advance, etc. In my mind, prior restraint doesn’t become possible the second you get paid to write.”

McClanahan argued days ago in the Daily Beast that Chuck Cooper actually threw Bolton under the bus in a major way.

“[Bolton’s] lawyer, Chuck Cooper, wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed this week intended to put public pressure on the White House. In it, Cooper volunteered that Bolton had violated both his NDA and perhaps a few criminal laws, including the Espionage Act,” he wrote. “Now, even if Bolton’s book is never released, he is facing stiff penalties. As unforced legal errors go, that’s a doozy.”

Storied First Amendment attorney Floyd Abrams argued the above-mentioned New York Times v. United States case before the Supreme Court in 1971. The case regarded the publication of the Pentagon Papers leaked by Daniel Ellsberg which showed various U.S. presidents had lied to the public about the police action in Vietnam.

“There’s no difference between the First Amendment rights of an individual journalist or the author of a book,” Abrams told Law&Crime. “Nor does a book publisher receive less protection than a newspaper publisher. What the Pentagon Papers Case did not and could not decide is just how grave a threat to national security is required before a prior restraint can be issued. What it did make clear is that while there is no flat First Amendment ban against all prior restraints there is an extremely high barrier against it.” (Floyd Abrams is the father of Law&Crime founder Dan Abrams.)

Tulane Law Professor Ross Garber offered some insight into how those legal precedents and theories might shake out in reality.

“President Trump’s legal team is surely aware how incredibly unlikely it is that a court would order a prior restraint on publication,” he told Law&Crime. “An injunction action may, however, be a tactic to warn Bolton and his publisher of other, potentially more viable, legal action should they proceed with publication.”

While the First Amendment protection against prior restraint is almost certain to hold the day in regards to Bolton’s book, that doesn’t mean the law is entirely silent on someone who reveals what the government deems to be classified information.

Indeed, the Barack Obama administration mounted a high-intensity campaign against the free press and classified sources–invoking the Espionage Act eight times against such leakers.

Ever mindful of Obama’s legacy, the Trump administration appears intent to surpass their immediate predecessor, using the controversial anti-leaking law at least eight times as of late 2019.

Garber noted that Trump has plenty of options should he go forward with the promise of legal action–both criminal and civil:

First is potential criminal exposure for disseminating classified information. Attorney General Barr’s public comments should heighten this concern. Second, a potential civil suit for damages based on violation of a non-disclosure agreement. In that context, an injunction action, even a futile one, may be setting the stage – putting Bolton and his publisher clearly on notice – for future legal action. The President could be hoping that the legal and financial risks will cause Bolton and his publisher to rethink their current publication plans.

“We’ll see what happens,” Trump said. “They’re in court–or they’ll soon be in court.”

That, at least, seems entirely likely here.

Update: The Trump administration filed a lawsuit against Bolton several hours after this story was published purporting to enjoin him from publishing his memoir over breach-of-contract issues and accusing him of “compromising national security.”

Read that story here.

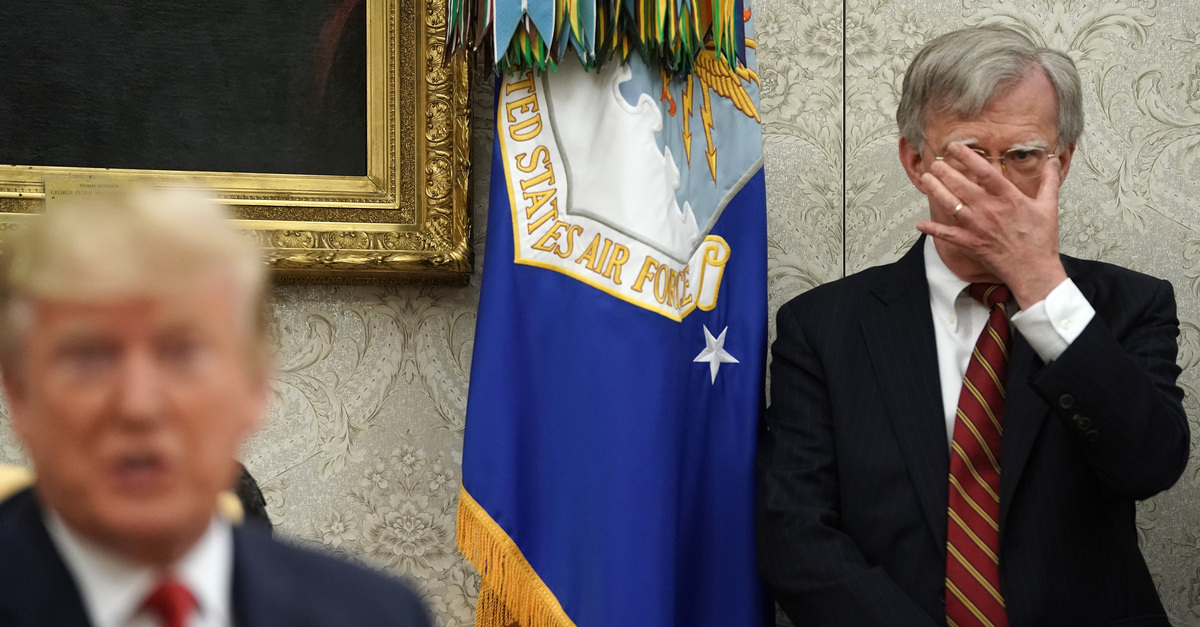

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]