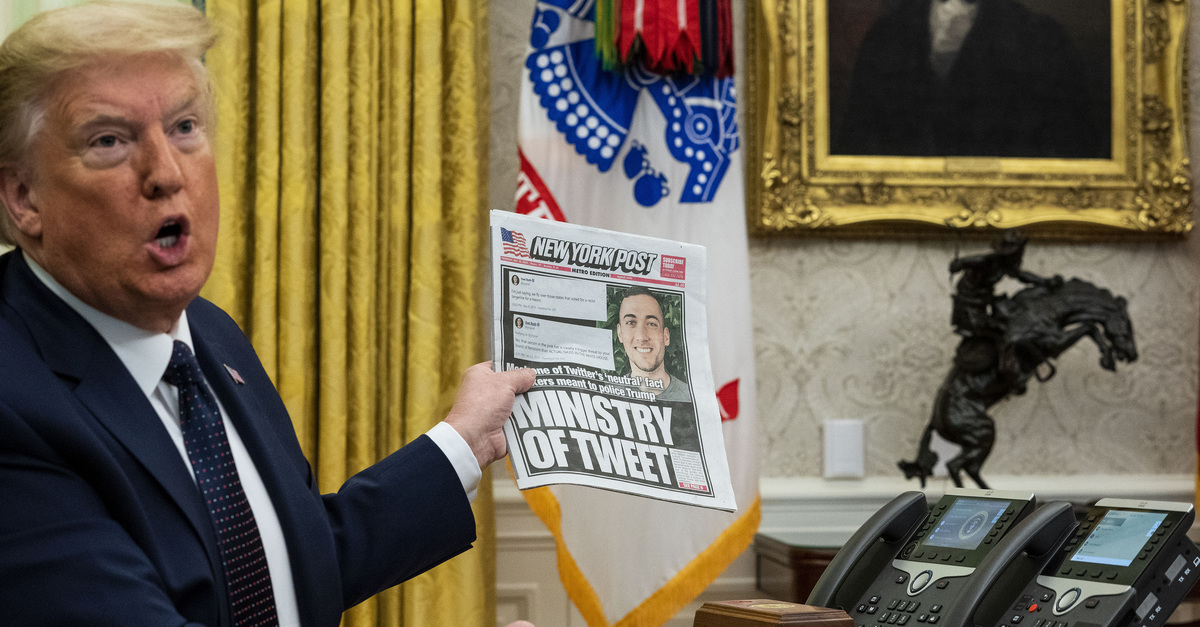

President Donald Trump signed a controversial executive order on Thursday purporting to undermine liability protections that have long formed the backbone of the internet as Americans know it.

“They’ve had unchecked power to censor, restrict, edit, shape, hide, alter virtually any form of communication between private citizens or large public audiences,” Trump said just before signing the order–referring to social media companies like Google and Twitter. “There is no precedent in American history for so small a number of corporations to control so large a sphere of human interaction.”

Fashioned as a defense of freedom of speech, the 45th president’s executive order is more likely to silence speech and inhibit the American tradition of largely unfettered online expression, according to First Amendment lawyer of New York Times v. Sullivan fame Floyd Abrams.

“I think this a threat to free speech,” Abrams Thursday said during an appearance on Dan Abrams’ Sirius XM radio show (Dan Abrams is the founder of Law&Crime, the son of Floyd Abrams, and the host of the Dan Abrams Show on SiriusXM’s POTUS channel). “It really has the potential to chill speech. Because surely the easiest way that the Twitters of the future can avoid problems like this is not to fact check, no matter how false the information is, no matter how outrageously false the information is. The temptation–at least–will be is: ‘Why do we need to spend all this money to get all the criticism and the like, and to risk antagonizing the president and all of the people he’s appointed to all of these places.'”

Floyd Abrams was referring to the genesis of the current imbroglio.

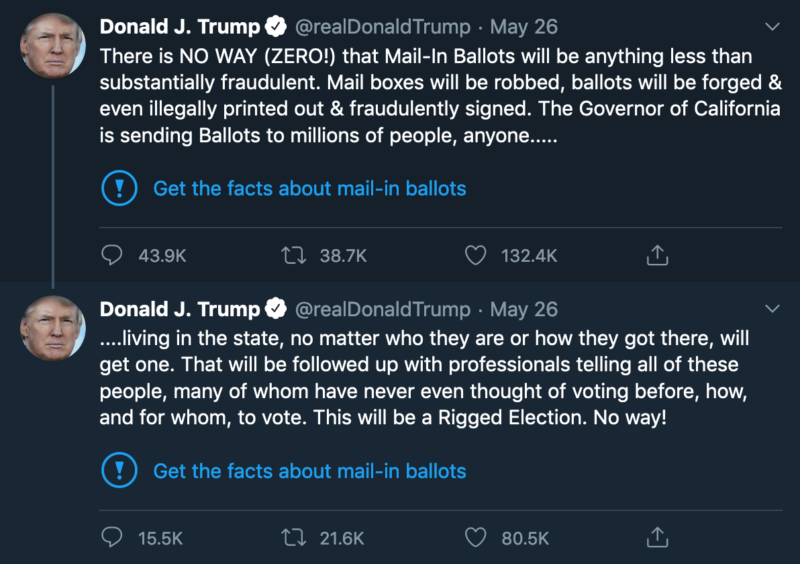

Trump has long been a fan of Twitter but acrimony unfolded in real time earlier this week when the president’s latest pet project and focus of scorn–alleged fraud inherent in vote-by-mail systems–was fact-checked by Jack Dorsey’s social media giant.

….living in the state, no matter who they are or how they got there, will get one. That will be followed up with professionals telling all of these people, many of whom have never even thought of voting before, how, and for whom, to vote. This will be a Rigged Election. No way!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 26, 2020

Trump promised swift action targeting social media entities and swiftly delivered–in the process validating a longstanding conservative movement conspiracy theory about censorship of right-wing speech and authors. In fact, social media companies have worked with conservative outlets in efforts to placate their complaints over the years–a move that many critics saw as an over-correction and capitulation to organized right-wing interests.

Still, Trump is the president and an executive order will, at least initially, hold institutional heft and the imprimatur of legitimacy. His agency subordinates will likely work to realize his intended aim. And, Abrams said, that will prose problems in the short term at least.

“At the end of the day, I’m confident, maybe wrong, but I’m confident that the administration will not be able to prevent Twitter and its competitors from putting in their own ultimate, for themselves, judgment that something the president–or anyone else–says online is inconsistent with the truth,” he predicted.

The issues implicated by Trump’s order, however, will have to be litigated. And that could take some time. In the interim, free speech will suffer as a result, the storied constitutional attorney insisted.

“The problem is that the fix is in–effectively–effectively, because the president speaks for this administration and he has made it very clear what results he wants,” Abrams cautioned. “There’s a major First Amendment issue at the heart of all this,” Abrams went on. “The First Amendment issue is not whether Twitter is entitled to protection based on what people say on Twitter. That’s been decided, so far, by Congress–saying, as Dan [Abrams] said, that there can’t be liability.”

The elder Abrams was referring to the Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1996, a federal law that, due to the Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence, doesn’t actually have any teeth when it comes to its original anti-indecency at all.

The extant and relevant portion of the CDA is Section 230, a lightning rod provision which some legal scholars have termed even “Better Than the First Amendment” by due to the expansive speech protections that emanate from that section of the statute.

“Section 230 provided that no interactive computer service should be treated as the publisher or speaker of third-party content, and that efforts to moderate content should not create such liability,” Texas A&M University School of Law Professor Brian Holland noted in a defense of the provision arguing for internet exceptionalism.

Holland elaborated §230 viz. law and internet development:

[A]lthough the immunity provided by Section 230 arguably mitigates the legal incentives for online intermediaries to deter and remedy certain negative behavior, it does not eliminate those legal incentives. Section 230 expressly states that it has no effect on criminal law, intellectual property law, or communications privacy law. These external norms remain applicable to and enforceable against both content providers and intermediaries in the online environment. Perhaps even more significantly, although Section 230 removes legal incentives to enforce the norms expressed in tort law, law is certainly not the only incentive for an intermediary to act. Communal, commercial and other incentives also play a role. Indeed, Section 230 immunity allows intermediaries the freedom to intervene in a multitude of ways. Thus, individual harms and marketplace security can be addressed through alternate legal regimes and internal incentives.

In essence, §230 is the basis of America’s current internet regime and, in no uncertain terms, Holland maintains: “reforming the statute to narrow the grant of immunity would significantly damage the online environment—both as it exists today and as it could become.”

Trump’s executive order ventures forth with the underlying idea that §230 immunity cannot apply to social media companies who moderate–or fact-check–content. The order goes on to instruct relevant agency heads at the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission to study new regulations that operate with that overarching criterion in mind–presumably seeking to fill gaps using the above suites of law that Holland notes are expressly inapplicable to the statute as written.

Any real action, of course, would be difficult for administrative agencies–always the scourge of reactionaries and conservatives excerpt for when they are in control of them–to effectuate absent action from Congress. And, despite the Democratic Party’s efforts to collaborate with Trump on most of his big ticket items, initial responses from Democrats suggest that undoing the modern state of the internet is not in line with their current priorities.

And while the damage here for speech could be difficult to unwind, the First Amendment garb donned by Trump is likely to be his eventual downfall.

“The First Amendment issue is: can you shut up the social media entities when they engage in what they view as fact-checking?” Abrams asked. “And I don’t think you can. I’m confident that that would violate the First Amendment. And, at the end of the day, that’s what this is all about. No matter what the results are of any internal studies. What is sought here by the president, what is sought here by the drafters of the executive order, is a limitation on speech. And that’s what the First Amendment does not allow.”

[image via Doug Mills-Pool/Getty Images]