Tex McIver (center) listened as his jury was polled in 2018. His attorneys Amanda Clark Palmer and Bruce Harvey flanked him; co-counsel Don Samuel was barely visible between Harvey and McIver. (Image via WAGA-TV/YouTube screengrab.)

The Georgia Supreme Court on Thursday reversed the the most serious convictions of Claud Lee “Tex” McIver III, the Atlanta attorney who in 2018 went to prison on charges of felony murder, aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, and influencing a witness in connection with the shooting death of his wife Diane McIver, a millionaire businesswoman, on Sept. 25, 2016.

The jury acquitted the defendant of malice murder. A trial court in 2018 threw out additional charges that McIver allegedly tried to influence two witnesses, Bill Crane and Thomas Lee Carter, Jr., because the facts of the case did not fit the crime charged.

However, McIver was convicted of trying to influence a third witness, family friend Dani Jo Carter. That conviction — for trying to influence Dani Jo Carter — remains on the books. The Georgia Supreme Court overturned the more serious felony murder and aggravated assault convictions.

The reason, the Court said, is because the trial court committed reversible error by refusing to allow the jury to consider a charge of involuntary manslaughter — which is based on the lesser legal standard of criminal negligence.

The involuntary manslaughter “charge was authorized by law,” Presiding Justice Michael P. Boggs wrote for a unanimous Court, “and some evidence supported the giving of the charge.”

Boggs said the trial court should have allowed the jury to consider the lesser involuntary manslaughter count and that was “highly probable” that the court’s failure to do so “contribute[d] to the jury’s verdicts.”

“We therefore reverse McIver’s convictions for felony murder and possession of a firearm in the commission of a felony,” the justices said in a voluminous 97-page opinion.

“The jury could have concluded – as McIver argued – that the evidence presented here did not meet the statutory definition of reckless conduct,” Boggs wrote elsewhere. “But the jury was given no alternative instruction regarding criminal negligence, a mental state more culpable than pure accident and arguably more consistent with the evidence at trial.”

Diane and Tex McIver appear in an image obtained by the television program “48 Hours.” (Image via CBS News/YouTube screengrab.)

Justice Boggs also wrote that McIver’s trial court judge improperly allowed prosecutors to use evidence that “lacked relevance” to the issues at hand — or evidence with a “probative value . . . substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice.”

The high court summarized the facts as follows:

The evidence presented at trial showed the following: Late in the evening of September 25, 2016, McIver, Diane, and Diane’s close friend, Dani Jo Carter, were on their way back from a weekend at the McIvers’ property in Putnam County, driving to Diane’s condominium in the Buckhead area of Atlanta after a stop for dinner in Conyers. Carter testified that she was driving, Diane was in the front passenger seat, and McIver was in the rear passenger seat, at times conversing and at other times asleep. Carter was not aware of any argument or disagreement between Diane and McIver that weekend or during the drive.

When they got onto the Downtown Connector in Atlanta, traffic was heavy, and Carter said they needed to get off the interstate and go up Peachtree Street. Diane said something to McIver, but he did not respond, and Diane told Carter to get off at the Edgewood Avenue exit. After they exited the interstate, McIver said, “Girls, I wish you hadn’t done this. This is a really bad area,” and asked Diane to hand him his gun from the center console. Diane handed him the gun, a .38-caliber revolver, which was not in its holster, which was also in the center console, but rather in a plastic grocery bag.

That turned out to be fatal. Again, according to the state Supreme Court’s retelling of the matter:

Diane instructed Carter to turn onto Piedmont Road and continue north. Carter assumed that McIver had fallen asleep again, because he did not join in their conversation. Sometime later, they were stopped at a traffic light on Piedmont Road, at 14th Street, when Carter heard several clicks and asked what Diane was doing; she responded that she was locking the doors. At that moment Carter heard a loud “boom” and Diane swung around and asked, “Tex, what did you do?” McIver responded that “the gun discharged.” Carter saw the gun in McIver’s hand, pointing down, still in the plastic bag. The bullet passed through the back of the front passenger seat, striking Diane in the back.

“At the hospital, when asked how the shooting occurred, Diane told doctors it was an accident,” Boggs wrote. “Carter told the police it was ‘a horrible accident.'”

“Diane died during surgery as a result of internal injuries to her spine, pancreas, kidney, and stomach,” Boggs noted. “McIver told the police that he fell asleep with the gun in his lap and the gun fired, and that he made statements at the hospital that the gun discharged accidentally when the car went over a bump.”

At one point during the trial, an expert witness who was handling McIver’s gun accidentally triggered the empty firearm in front of the jury — even as prosecutors attempted to argue that a significant amount of force was necessary to set off the weapon.

“Oops,” said witness Zachary Weitzel of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation after the accidental trigger.

#TexMcIver – Watch and listen very carefully at time stamp 0.32. Prosecution’s gun expert accidentally pulls the trigger and says, “oops”. Does this help the defense? Is the trigger that easy to pull in that mode? We’ll have our team break it down for you tomorrow. pic.twitter.com/3ctZeJaxjW

— Law&Crime Network (@LawCrimeNetwork) March 30, 2018

Prosecutors asserted that the case was one of malice murder — driven in part by greed and a desire to control Diane McIver’s financial and real estate empires. The jury only half-bought that assertion as evidenced by the mixed verdict; indeed, the Georgia Supreme Court noted that the jury was initially hung.

The state’s highest court schooled prosecutors on exactly what they cannot do if they choose to re-try McIver in the future. What prosecutors cannot do, the high court concluded, was gin up inferences and suppositions unsupported by any concrete evidence that Diane McIver may have created a second version of her last will and testament that may have given Tex McIver some motive to kill his wife. The court went on about this issue at length:

No second will was ever found despite an intensive search; the McIvers’ estate planning attorneys knew of no such will; and no evidence was presented of the supposed will’s contents or whether its provisions were advantageous, disadvantageous, or neutral to [the defendant] McIver. Moreover, no evidence was presented that McIver knew of such a will or its contents, or had access to it.

Yet the State argued that the mere existence of a supposed second will, with no evidence of its provisions or of McIver’s knowledge of or access to it, was relevant to show that he had a financial motive to kill Diane and to show that when he shot her, he did so with the intent to kill or at least violently injure her. The State noted that the supposed second will theoretically could have left all Diane’s property to someone other than McIver, including her interest in the ranch property. But, as McIver points out, the supposed second will could not have affected the disposition of Diane’s interest in the ranch property, because the McIvers held the property as joint tenants with right of survivorship.

In other words, the Court believed that the prosecution’s case was flimsy: “the evidence connecting that alleged motive to any actions that McIver took to intentionally kill his wife was thin,” Justice Boggs wrote.

“Indeed, the State’s evidence of intent was weak, as no witness testified to any disagreement or quarrel between McIver and Diane, and many witnesses testified that they were very much in love,” Boggs said elsewhere in the opinion.

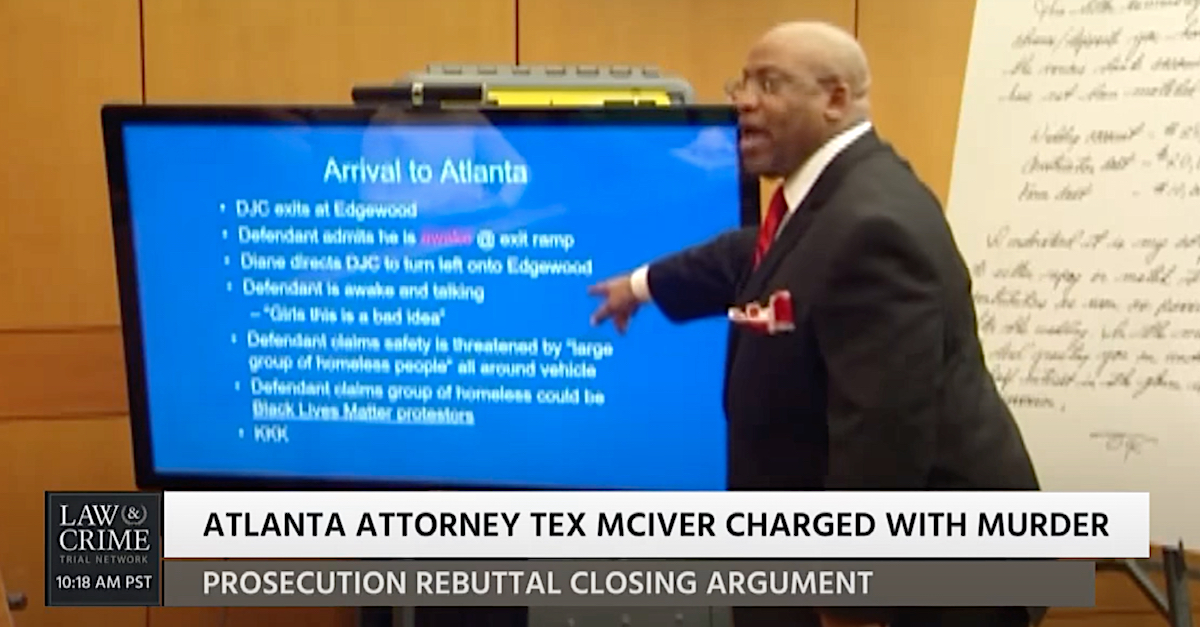

Elsewhere the Court noted “particularly and with disapproval” that a prosecutor displayed “a PowerPoint slide with a bullet point reading ‘KKK’ during his closing argument.”

The Georgia Supreme Court chided the state over an “irrelevant” reference to the KKK on a PowerPoint slide discussed in front of the jury by then-prosecutor Clint Rucker. (Image via the Law&Crime Network.)

“Questioned at oral argument in this Court, the State ultimately acknowledged that no evidence was produced at trial to support any inference that the Ku Klux Klan was relevant to this case,” the high court noted.

McIver’s attorneys said the state was using a “constant drumbeat of racial animus” to “inflame the passion of the jury,” and the Court therefore “strongly caution[ed] the State that this or any similar behavior is not to be repeated upon any retrial of this case.”

Other elements of racial animus, however, were relevant, such as McIver’s claim that he wanted his gun because he might encounter “Black Lives Matter protesters,” the Court calculated. Even though McIver complained that the state went through great lengths to use that evidence against him, the Court said it was “highly probative . . . because it was McIver’s own description of why he asked for his gun.”

The verdicts in the case have long been criticized by a number of legal analysts — including, for the sake of ethical disclosure, the person writing this report — who watched the case unfold on the Law&Crime Network.

Tex McIver’s mugshot. (Image via the George Department of Corrections.)

“We are delighted with the unanimous decision of the supreme court reversing Tex McIver’s conviction,” his attorneys Amanda Clark Palmer, Don Samuel, and Bruce Harvey said in a joint statement to Law&Crime. “He was deprived of a fair trial because the jury was not given the opportunity to find that the shooting was entirely the result of negligence , as opposed to an intentional killing. He was entitled to a fair trial and did not get a fair trial. We look forward to showing the next jury that he is not guilty of murder.”

A spokesperson for the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that the office “will evaluate the case and make a decision on how to proceed in the near future.”

Read the full opinion below: