Bianca Devins. (Image via the Devins family.)

A federal judge on Thursday dismissed a civil lawsuit against a district attorney accused of distributing “snuff” films of a teen victim’s sex acts and subsequent murder after the DA locked up the killer.

The complicated case by the victim’s family was largely dismissed on procedural and technical grounds but did answer one key legal question: the judge said New York State’s open records laws could not be used to obtain child pornography from government agencies who prosecute offenders. Federal criminal law preempts that grave and untoward possibility, the judge ruled.

That big picture conclusion, however, offered no immediate relief to the family of the victim; the judge concluded that only a tiny sliver of the original case could be re-filed in state court should the plaintiffs choose to elect that venue.

The Murder

Bianca Devins, 17, of Utica, New York, was killed on July 14, 2019 — the date of a popular road race which brings thousands to the city in the central part of the state each year. Devins was killed on a dead-end street just blocks from the starting line.

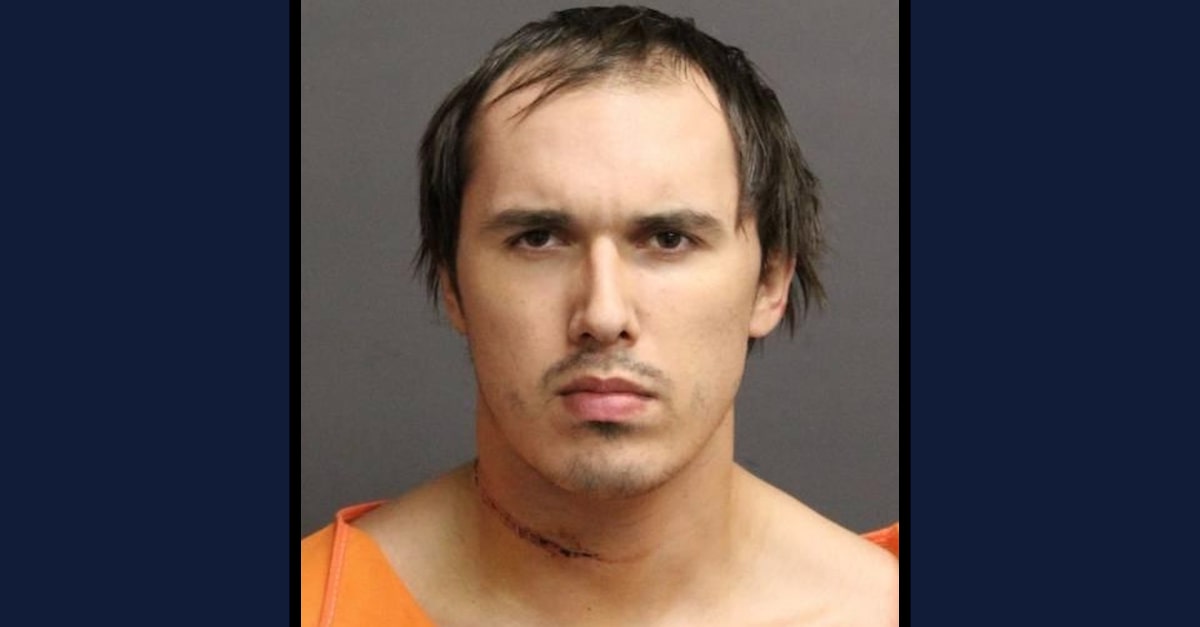

Brandon Clark, then 22, of Bridgeport, New York, pleaded guilty in February 2020 to murdering Devins. He was sentenced in March 2021 to serve 25 years to life in prison.

The case became internationally famous because Clark recorded a pre-murder sex act, evidence of the gory crime itself, and his subsequent attempts to harm himself after the fact. He posted evidence of his heinous exploits online — apparently to infuriate Devins’ online admirers — and then called 911.

“My name is Brandon, the victim is Bianca Michelle Devins,” the defendant’s 911 call indicated. “I’m not going to stay on the phone for long, because I still need to do the suicide part of the murder-suicide.”

The police quickly arrived on the scene and wrestled Clark to the ground as he held a knife to his throat.

A penumbra of legal issues remained outstanding after the criminal case concluded with Clark’s incarceration.

Brandon Clark appears in an Oneida County, New York Sheriff’s Office mugshot. Note the self-inflicted injury to the neck.

Estate Sues County, Prosecutor

The Devins family sued Oneida County District Attorney Scott McNamara, the DA’s office as an entity, and the county itself for allegedly providing the salacious recordings of sex and death to several media organizations pursuant to open records requests filed under New York State law.

As Law&Crime previously reported, the family’s July 2021 federal civil lawsuit argued that the prosecutor’s decision to fulfill the open records requests violated federal child pornography laws. Devins was 17 when she died; federal child pornography laws criminalize the sharing of prurient portrayals of individuals under the age of 18. New York State child pornography laws are different; they apply to individuals under 17.

In short, the Devins family’s lawsuit argued that the difference between New York and federal law tripped McNamara up.

McNamara, his office, and the county rebutted the accusations by arguing that Devins lost her privacy rights when she died. The various defendants asked a federal judge in Syracuse, New York, to dismiss the case in August 2021.

Also in August 2021, the prosecutor and his office agreed not to share any videos of Devins “being murdered, having sex, nude, or in a state of undress” while the case was pending.

By late August 2021, CBS Broadcasting, Inc., one of the media companies referenced (but not sued) in the original complaint, said it would hand over to the court a hard drive of material it obtained from the DA’s office pursuant to the now-infamous open records request.

The original lawsuit also said A&E, MTV and NBC’s Peacock TV “were also trying to cover the case.”

The docket remained quiet for more than a year — until Thursday.

Oneida County District Attorney Scott McNamara appeared on a talk show on WIBX radio in 2015. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

Federal Judge Dismisses Case

On Thurs., Sept. 29, 2022, U.S. District Judge Glenn T. Suddaby of the Northern District of New York dismissed the case in its entirety via a highly complex 45-page decision and order.

The judge, who is a former U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of New York, explained the posture of the case in an opening paragraph:

Generally, in its Complaint, Plaintiff asserts four claims arising from its allegations that Defendants gave to the media and public “sex and murder videos” and “nude images” of Bianca Devins (“Devins” or “Decedent”) following her murder by Brandon Clark on July 14, 2019: (1) a claim against all Defendants for knowingly distributing materials containing child pornography under 18 U.S.C. § 2252A; (2) a claim against all Defendants for personal injuries under 18 U.S.C. § 2255; (3) a claim against all Defendants for negligence under New York State law; and (4) a claim against Defendant Oneida County for negligent supervision under New York State law.

The defendants asserted 12 reasons to dismiss the quadruple causes of action, the judge noted. Among them were procedural hurdles — such as the plaintiff’s alleged failure to file notices of the action against the municipal defendants in accordance with New York State law — and arguments that the District Attorney’s Office wasn’t a proper party to sue because it is merely an “administrative arm of Oneida County under New York State law.” Also asserted as a defense was that the lawsuit didn’t “plausibly” suggest that District Attorney McNamara “was personally involved in the alleged dissemination of materials that Plaintiff claims contain child pornography.”

The defenses, in essence, attempted the following two-step: (1) to heap all of the potential liability upon Oneida County itself, and (2) to assert that Oneida County could not be held liable for several reasons. For instance, the county argued that federal child pornography laws do not apply to municipalities. The county also argued that “it cannot be liable for disclosing the alleged pornographic material merely by complying with the New York State Freedom of Information Law.” The county further argued that “qualified immunity” applied: “it was objectively reasonable for Defendant Oneida County to believe that disclosing the contents of the relevant criminal investigation file — including the materials allegedly constituting child pornography — was lawful,” the judge noted while recapping the various defenses.

The plaintiff — technically named as the estate of Bianca Devins — attempted to rebut each of those defenses.

The judge spend scads of pages recapping the myriad arguments, defenses, and status of federal law before arriving at several complicated legal conclusions.

Estate Suffered Economic Harms and Had Standing to Sue

First, the judge disagreed with the defense argument that Devins’ death meant the end of her estate’s interests in her privacy and therefore lacked standing to sue — but with some trepidation:

Here, granted, the Court has some difficulty finding that the dissemination of the child pornography in question to media outlets (including the producers for “48 Hours” and A&E) could have caused an intangible reputational injury to Plaintiff (Decedent’s estate). This is because, even if the dissemination caused Devins’ Instagram account to grow in followers from 2,000 to 166,000 — some of whom besieged the accounts of her family members with images of Devins’ dead body — the injury (which the Court views more as emotional than reputational) was inflicted on Devins’ family, not her estate.

That aside, the judge agreed that the estate had indeed suffered economic harm because it was forced to sue to “destroy the content” and because it was “forced to repeatedly communicate — through counsel — with the District Attorney’s Office regarding the material and Defendants’ dissemination of it.”

Those harms, the judge said, gave the estate legal standing to bring the action in the first place.

Court Lacked Subject Matter Jurisdiction over Municipalities

Judge Suddaby, a George W. Bush appointee, then concluded that the court lacked subject matter jurisdiction over all of the defendants except various “John Does 1-20 in their individual capacities” and against McNamara in his individual capacity. The core rationale here was that the municipalities in question were not sued in strict accordance with New York State’s intricate procedural laws.

The judge engaged in a painstaking critique of the Devins estate for filing the lawsuit in federal court without waiting 30 days after providing a relevant notice required under state law.

The estate argued that it jumped the gun on the 30-day window because it was terrified of the snuff films being disseminated further and begged for the swift issuance of temporary restraining order. However, the judge said those fears were not important enough to override the procedural laws in place for such matters.

“Generally, the exhaustion doctrine requires a party to exhaust available administrative remedies before invoking the jurisdiction of the courts,” the judge wrote while quoting local and U.S. Supreme Court case law (we’ve omitted the legal citations and internal punctuation).

The judge continued, this time citing a different case:

Furthermore, Plaintiff has failed to provide the Court with any previous instances in which a federal court elected to conduct the analysis that Plaintiff has requested. Because “federal courts do not have jurisdiction to hear complaints from plaintiffs who have failed to comply with the notice of claim requirement, or to grant permission to file a late notice,” the Court cannot grant Plaintiff’s request that it analyze its premature notice of claim under the standard that governs a late notice of claim.

“Here, Plaintiff has failed to meet its burden of showing that it complied with the notice-of-claim requirements,” the judge added. “In strictly construing these requirements, the Court finds that thirty days had not elapsed between the date on which Plaintiff served its notice of claim on Defendant Oneida County and the date on which Plaintiff filed its Complaint. Therefore, even accepting as true the allegations contained in the Complaint and drawing all reasonable inferences in Plaintiff’s favor, the Court finds that Plaintiff’s negligence and negligent supervision claims are procedurally barred.”

Judge Suddaby dismissed the case against the municipalities “without prejudice,” which means it technically can be re-filed. However, the judge said that precise mode of dismissal was the only one available to him in a subject-matter-jurisdiction decision. Accordingly, the judge rather bluntly noted that “granting leave to amend is unlikely to be productive” and that “any amendment would be futile” — as if to say he is not willing to re-hear the matter against the municipal defendants named in the case regardless of the case being dismissed without prejudice.

Negligence Claims Against District Attorney and “John Does”

The judge then turned to a remaining negligence claim against McNamara in his official capacity and the unnamed John Does who were sued individually. Here, a key split emerged.

The judge noted that the aforementioned procedural hurdles were not necessary for individual defendants who acted in their personal capacities. Specifically, the judge referenced concerns that one of the so-called John Does, a Utica Police Officer, had supposedly shared “body cam footage from the crime scene” with individuals gathered at a local tavern.

“The Court has difficulty understanding how this officer was engaged in conduct for the purpose of serving his or her employer when he or she shared this body camera footage,” the judge wrote in a short scribble that mildly scolded the unnamed officer who allegedly engaged in the conduct.

The judge said the court retained subject matter jurisdiction over such individuals acting purely in their individual personal capacities but not over McNamara for alleged negligence in his individual official capacity.

The judge said he was not convinced that Oneida County was “required” to indemnify McNamara for any conduct he may have committed but dismissed McNamara from the negligence claim because his alleged actions were more official than personal.

Open Records Laws Do Not Allow the Transmission of Child Porn

The judge concluded that federal child pornography laws preempt New York State’s Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) and that the defendants could not argue the latter against the former.

First, the judge articulated that he did not believe the recordings in question were “records” under the meaning of FOIL.

Second, he said “the federal statutes at issue, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2252A and 2255, do not contain an exception for governmental agencies to distribute materials constituting child pornography merely for the reason of complying with various states’ freedom of information laws.” In other words, the judge said the state’s FOIL law could not be interpreted to allow government officials to transmit child pornography via open records requests because federal law already regulated that field of conduct.

The judge wrote:

Based on the above analysis, it is abundantly clear to the Court that Congress did not intend to create a loophole to shield parties from civil (and even criminal) liability merely because they had an obligation to comply with individual states’ freedom of information laws (or, alternatively, could use their discretion when determining whether to withhold records in accordance with an exemption under such laws), but that, rather, when Congress enacted 18 U.S.C. §§ 2252A and 2255, it intended to occupy the entire field of regulation related to eradicating the creation and distribution of child pornography.

“[T]the Court refuses to hold that Defendants may avoid liability through reliance on New York State’s FOIL,” the judge wrote. “For these reasons, the Court rejects Defendants’ argument that Defendant Oneida County is immune from liability on Plaintiff’s first and second claims due to FOIL.”

The opinion might foreclose future attempts to secure lurid depictions of teen sex and death from government agencies, but it did not save much remaining hope for the Devins estate.

“Lack of Capacity to Sue”

By this point in the complex opinion, the judge had run through many of the claims and the defendants in a fashion that left virtually none standing — all while he admitted that the core legal contention had merit.

However, the judge detonated the overall thrust of the federal claims in scorched-earth fashion by determining that the estate had no capacity to sue using federal pornography laws.

“Capacity” to sue is similar to the concept of “standing” (discussed above). However, they are, indeed, different: standing is part of the “larger question of justiciability,” the judge wrote (citing the New York State Court of Appeals), but capacity “concerns a litigant’s power to appear and bring its grievance before the court.” Capacity, in other words, depends “purely upon a litigant’s status,” the judge noted.

And, here, the judge concluded that the estate had no capacity to sue over the issue at hand because Devins was dead.

The estate had attempted to argue that Devins began suffering injuries the moment Clark began to record her while she was still alive; those injuries continued, according to the state, to include the alleged acts of the DA’s office.

Judge Suddaby disagreed with that attenuated chain of logic:

Although the material containing video of Devins was captured before her death on July 14, 2019, Defendants’ injury to Plaintiff (for purposes of her two federal claims) occurred when they disseminated the child pornography regarding Devins (which was after her death).

[ . . . ]

Therefore, the Court agrees with Defendants that Devins’ “personal representative has the authority to bring causes of action that were viable at the time of [her] death, [but] not claims that arose after . . . her death.” [Citations omitted.] Here, Plaintiff’s first and second claims were not viable at the time of Devins’ death for the following three reasons: (1) they have not been asserted against Clark; (2) they do not arise from Defendants’ conduct occurring before Devins’ death; and (3) they have not been asserted by Kimberly Devins in her representative capacity as the administratrix of the Estate of Bianca Devins (but rather were asserted expressly by the Estate itself).

Thus, Judge Suddaby torpedoed the first and second causes of action in their entirety.

What remained were the third and fourth causes of action (involving supplemental state law negligence claims) against McNamara in his personal capacity and the various yet anonymous John Does in their personal capacities.

Estate Didn’t Prove DA’s “Personal Involvement”

Judge Suddaby wrote that the estate failed to suggest that McNamara had done anything to further his own personal interests (as compared to those of his employer).

“Plaintiff’s Complaint does not allege facts plausibly suggesting that Defendant McNamara was personally involved in the disclosure of the material in question while acting in his own personal interest (and outside the scope of his official duties),” the judge wrote.

“For example, Plaintiff’s Complaint alleges that counsel for Plaintiff sent two letters to Defendant McNamara, not that he personally responded to (or even read) those two letters,” the judge noted.

The judge concluded that office staffers — not McNamara personally — likely transmitted the recordings to the media. He also said McNamara never personally promised the Devins family that the material would never be disseminated — that promise was allegedly uttered by an assistant, not McNamara himself.

“Official Capacity” Claims

Having scuttled the municipal claims in earlier paragraphs, the judge added a note to reiterate that he was dismissing all of the claims that McNamara and the remaining John Does had acted in their “official capacity.” Here, the judge offered a mere and passing conclusion that those claims were duplicates of the municipal liability claims that had already been rubbished.

The judge then dispatched several other causes of action against the unnamed defendants.

State-Law Claim Against “John Does” 1-20

The only cause of action left open at this point in the opinion was a state law claim negligence claim against John Does 1-20 in their individual personal capacities. That issue was decided quite simply based on the nature of federal court jurisdiction.

Federal courts often hear federal claims (here, the first two claims) and “supplemental” state-law claims (here, the latter two claims) all at once in order to save the parties the hassle of engaging in concomitant litigation in two separate forums. However, federal courts can only exercise supplemental jurisdiction when state-law claims are appropriately tacked onto similar federal claims.

Here, because the judge dismissed the federal claims, the state law claims could not survive in federal court. However, the judge said they could survive in state court.

The judge did not directly address some of the remaining defenses because he said doing so was not necessary.

Finally, the judge said the parties must indicate within 30 days how they wish the court to dispose of the hard drive of material CBS provided to the court last year.

Manhattan-based attorney Carrie Goldberg, who represents the estate, reacted to the judge’s decision and order as follows:

Although the matter was dismissed, it was without prejudice. So we could amend and refile.

This was a case of first impression with an estate suing under CSAM [Child Sexual Abuse Material]. And although the matter was largely dismissed, it contains important precedent that will protect victims and their families. For instance, it rejects Oneida County’s bizarro argument that it was justified to disseminate CSAM because FOIL law preempted it. Instead, the court recognized that this was exactly a circumstance where Oneida County should have balanced the privacy interest of not disclosing.

Importantly, the judge also said that estates do have standing to bring claims on behalf of deceased victims of child pornography. Unfortunately, the court’s protections for deceased victims of CSAM only went so far. It was limited to harms that occurred during their lifetime and according to the court, since Oneida County disseminated the nude pictures and videos of Bianca AFTER she died, they had no liability. We argued that because the images were illegally captured during her lifetime, the liability should then attach to folks who obtain the images and then unlawfully disseminate them. Oneida County of course would not be liable for possessing the images, but in a moral society, should be on the hook for disseminating them. This decision creates a very serious concern suggesting there is no civil liability against people who share and exchange or even sell pictures of nude children so long as the sharing happens after the depicted person has died. I see this as a frighteningly close as legalizing a category of CSAM. Especially with the huge spikes in suicide among adolescents related to social media, this would make the contents of nudes on their phones fair game. I’m also aware of many children who committed suicide because they were sextorted. Again, their nudes would be fair game for further dissemination under this decision. Law enforcement could still hold these disseminators liable, but nobody acting on behalf of the deceased child could.

We will be discussing options with our client.

McNamara did not respond to a Law&Crime email seeking comment.

The entire opinion and order are embedded below: