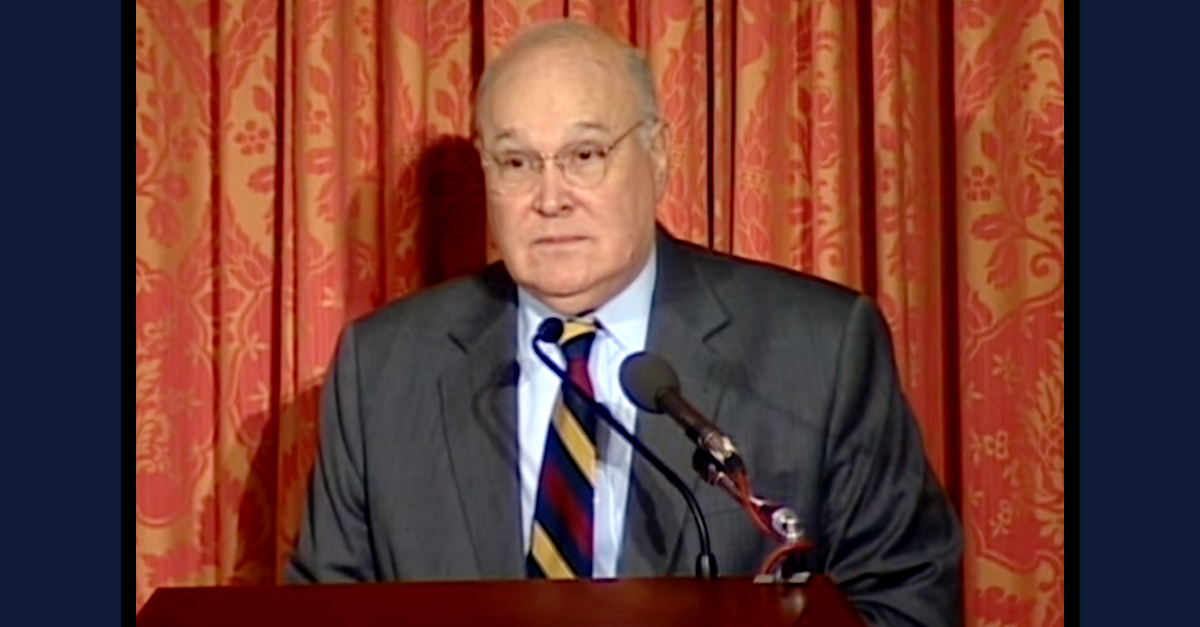

Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Dennis Jacobs. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

A judge on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals issued a scathing dissent in a New York case involving a man convicted of rape who claimed a trial court’s decision to deny him access to his accuser’s mental health records deprived him of his constitutional rights.

Terence Sandy McCray was convicted of first-degree rape and sentenced to 22 years in prison. The case stems from a 2009 encounter between McCray and his accuser, who is not named in the federal court documents.

McCray allegedly violent assaulted the victim in an abandoned home. He maintains that the encounter was consensual but that a violent confrontation ensued when the victim demanded money and tried to take his pants and wallet. The woman’s injuries were consistent with both versions of events.

At trial, McCray was denied access to all but 28 of more than 5,000 pages of the victim’s mental health records, which he says would have supported his defense. The victim had a history of PTSD, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, Tourette’s syndrome, attention deficit disorder, hallucinations, and three alleged sexual-abuse incidents. The trial judge had reviewed all the documents before deciding what to share with McCray, who says that the trial court violated his rights to exculpatory material under the 1963 landmark Supreme Court decision Brady v. Maryland. McCray also asserted that his Sixth Amendment right to confront his accuser was violated.

The New York appellate division, an intermediate appeals court, affirmed McCray’s conviction; so did the Court of Appeals — the Empire State’s highest court. McCray then sought relief from the federal courts. A judge in the Northern District of New York denied his petition but granted a certificate of appealability on Brady grounds nonetheless. McCray successfully moved to expand the question on appeal to whether the nondisclosures of the victim’s mental health records violated his Sixth Amendment right to confrontation.

As the majority opinion notes, McCray’s accuser was subject to a vigorous cross-examination by his lawyers, who asked the victim about her mental health status and treatment.

Two of the three judges on the Second Circuit panel — Richard J. Sullivan, a Donald Trump appointee who wrote the opinion, and Gerard E. Lynch, a Barack Obama appointee who joined him — found that the trial court did not violate McCray’s rights because he was given the aforementioned 28-page sample of his accuser’s records. The two-judge majority also held that the state Court of Appeals’ review of the case was not unreasonable. The majority further found that there was no binding precedent that a defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to confrontation extends to pretrial discovery.

Senior U.S. Circuit Judge Dennis Jacobs, a George H.W. Bush appointee, was not on board with that analysis.

“I respectfully dissent,” Jacobs began. “In a word-against-word rape case, the State turned over to the defense documents reflecting a variety of mental disorders of the complainant that rendered her vulnerable; but the State did not turn over documents reflecting her distortions of memory and reality, and an earlier report of rape. The withheld documents put the case in a wholly different light, raise powerful doubts about what happened, and would have opened the only promising avenues for investigation and trial strategy.”

While Jacobs’ legal analysis did, indeed, appear to respectfully disagree with that of the two other judges, he was far less circumspect when it came to criticizing the prosecutors in the case.

Jacobs wrote in his dissent (citations omitted):

The State now doggedly defends a conviction that it obtained thanks to a violation of due process. True, the initial mistake here was made by the trial judge. With 5000 pages of a medical file, the process of review somehow broke down. The critical documents were withheld from the prosecution as well as the defense. But after the trial, the successive state courts and the district court—and now my chambers—found documents that ‘put the whole case in . . . a different light’ and ‘undermine confidence in the verdict.’ A prosecutor who knowingly did what the trial judge did would be a menace. But good faith is irrelevant under Brady, and functionally, there is no difference between an error by the trial judge and a dirty deed by a prosecutor: the State has deprived the defendant of a fair trial. To McCray, in jail for 22 years, it is all one.

Jacobs wrote that while his colleagues “rigorously applied principles of finality and deference” in to their legal analysis, “those principles and constraints in no way bind a prosecutor.”

“A prosecutor who continues to enjoy a misbegotten victory is as much a menace as one who contrives it,” Jacobs continued. “Here, the Attorney General knows from successive appellate opinions that McCray, who is still in prison, was wholly denied the right to defend himself. Yet the Attorney General labors hard to maintain the advantage. The result here is that a person is more than halfway through a 22-year prison sentence, without a trial that anyone can now deem fair, and he is still without the opportunity to see the documents that could have acquitted him.”

In a withering final remark, Jacobs made his opinion of the prosecutor’s decision crystal clear.

“I don’t know what happened in that abandoned house; but it is clear what is happening here,” Jacobs wrote. “This is a sinister abuse. The last-ditch defense of such a conviction by the Attorney General is disreputable. Were I a lawyer for the State, I would not have been able to sign the brief it filed on this appeal.”

An attorney for McCray declined Law&Crime’s request for comment.

Read the ruling, and Jacobs’ dissent, below.

[Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.]